Over 12 days, the 2025 edition of New York’s Tribeca Film Festival screened 118 feature films, 93 of them premieres, featuring titles from all over the world and covering pretty much every imaginable genre and then some.

Not counting the numerous classic titles that were given high-profile retrospective screenings, I managed to see about half of the titles being presented, and my reactions to them were just as varied. Some of them were quite good, some were aggressively mediocre, and there were a couple so bad that the mind reels at the thought of what the titles that were rejected must have been like to allow them to sneak through. And yes, happily, there were even a couple of out-of-nowhere items that deliver their messages with such skill, style and audacity that it’s genuinely exciting and astonishing to watch unspool.

This year’s lineup seemed slanted a little more heavily toward documentaries than in the past, and, perhaps not surprisingly for a festival that has always attracted a heavy star contingent, a number of them were also celebrity-driven with a particular emphasis on music-related projects. Perhaps the highest profile of these was “Miley Cyrus: Something Beautiful,” a visualization of the top-selling singer’s new album of the same name as directed by Jacob Bixenman, Brendan Walter and Cyrus herself—while the results won’t make you forget such rock opera classics as “Tommy” or “Pink Floyd the Wall” anytime soon, they do make for an entertaining and occasionally eye-popping 55 minutes and the sequence bringing together Cyrus and supermodel Naomi Campbell on “Every Girl You Ever Loved” is undeniably iconic.

Also appealing to the younger generation were Eugene Yi’s “The Rose: Come Back to Me,” a chronicle of one of the most popular K-Pop bands in the world today, and “Rebbeca,” Gabrielle Cavanagh and Jennifer Tiexiera’s film observing pop star Becky G as she goes about recording her first Mexican-language album and embarking on her first headlining tour. While these films will no doubt be loved by their respective (and considerable) fan bases, they feel like they were made not because they had something to say, but because their competitors had films produced about them, and they wanted to get in on the fun.

For older viewers, there were films about two of the most iconic symbols of the MTV generation in Alison Ellwood’s “Boy George & Culture Club” and Jonas Akerlund’s “Billy Idol Should Be Dead”. In both cases, the subjects at hand are compelling and entertaining enough in recounting their meteoric rises to fame and drug-fueled crashes to almost, but not quite, make viewers forget that the films themselves are little more than extended episodes of “Behind the Music.” On the other hand, the late and legendary jazz musician (among many other things) Sun Ra certainly left behind a life and legacy worthy of cinematic treatment but Christine Turner’s “Sun Ra: Do the Impossible” doesn’t take any of the creative risks that he took throughout his career, disappointingly sticking to the standard-issue “American Masters” format instead of going out on a limb in the way that the material seems to call out for.

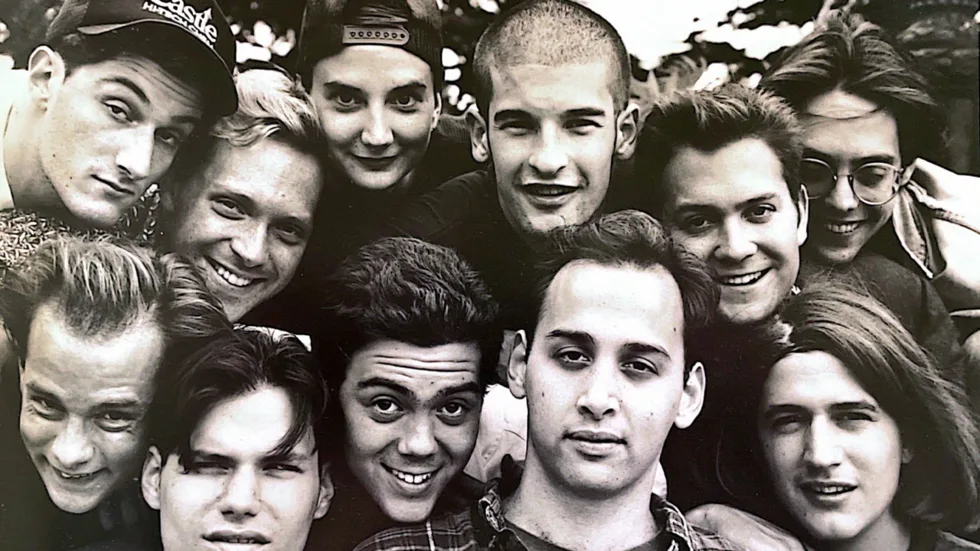

There were also a number of documentaries examining the world of comedy on display. Matthew Perniciaro’s “Long Live the State” chronicled the history and 2024 reunion of the sketch comedy troupe The State, which formed at NYU in the late 80s and soon afterwards landed a show on MTV that, while short-lived, became a cult favorite that helped launch the careers of such members as Michael Showalter, David Wain, Joe Lo Truglio and others who would go on to make their marks on American comedy over the last 30 years. Again, the film is pretty much for fans only—it insists upon their greatness without quite making the case for anyone who isn’t already in the bag for them and inexplicably glosses over what could have been the most interesting aspect, the prospect of coming back together after such a long time.

The legendary Dadaist comedian Andy Kaufman has been the subject of so many books and documentaries trying to figure out what made him tick, yet another film about him might seem superfluous. Clay Tweel’s “Andy Kaufman is Me” (featuring Dwayne Johnson and David Letterman among the array of co-producers) manages to set itself apart from the pack by offering insights into Kaufman and his approach to comedy from the man himself. This is done via archival materials supplied by his family that include numerous audio diaries, which help provide a fuller picture of him and his work, which still has the power to amuse, anger, and confuse people decades after his passing.

On the other hand, few would argue that Pat, the recurring “SNL” character from the early-’90s incarnation of the show, whose single joke was that she drove others to distraction by her apparent refusal to observe gender lines, has aged particularly well. In the intriguing “We Are Pat,” filmmaker Ro Haber grapples with the legacy of this divisive character and, with the blessing of Julia Sweeney, who created and portrayed Pat, gathers together a group of LGBTQ comedians to see if they can reframe the character in a contemporary context that acknowledges the vast changes in attitudes towards trans visibility and make them into something empowering instead of insulting.

This may sound like a lot of effort for a comedic premise that wasn’t that amusing in the first place, but it offers viewers a way of exploring shifts in comedic sensibilities and social attitudes.

One cannot have a film festival without including a few entries about the history of cinema itself, and Tribeca was no exception to that, coming up with a trio of fascinating titles. As you can probably surmise from the title, Jeffrey McHale’s “It’s Dorothy!” is yet another documentary revolving around “The Wizard of Oz” but puts the focus solely on the central character of Dorothy Gale and how she has been portrayed in various productions over the years. These range, of course, from Judy Garland’s legendary turn in the 1939 classic to Stephanie Mills’ equally memorable work on Broadway in the role in “The Wiz” to Fairuza Balk’s appearance in the fascinating 1985 semi-sequel “Return to Oz.” This study is based on observations from individuals who have played her, such as Balk and Ashanti, as well as devotees like Rufus Wainwright and John Waters, whose obsession with the film has been well-documented.

In his first feature, the charming and surprisingly moving “Runa Simi,” filmmaker Augusto Zegarra follows Fernando, a Peruvian voiceover artist whose online hobby of dubbing film clips into his native Quechua—as a way of allowing the nearly-extinct language to thrive and gain relevance—leads him on a quixotic quest to attempt a complete dub of “The Lion King.” The film observes as he tries to pull the project together while simultaneously attempting to secure permission from Disney for the endeavor.

About as far away from the likes of “The Wizard of Oz” and “The Lion King” as you could possibly get were the films of Andy Milligan, the insanely prolific exploitation filmmaker who, from the late ’60s through the ’80s, ground out lurid exploitation films over the years that brought together sex, violence, perverse situations and thoroughly unpleasant characters on beyond-minuscule budgets that left even the hardiest grindhouse viewers of the day feeling confused and icked out by what that had just witnessed. As bad as his movies were, he was clearly someone who, like any real artist, was consumed with trying to express themselves through their work (even if he ultimately wasn’t very good at it).

In their often-fascinating documentary “The Degenerate: The Life and Films of Andy Milligan,” co-directors Josh and Grayson Tyler Johnson examine Milligan’s bizarro personal and professional legacy through interviews with former colleagues (who still seem poleaxed by the experience) as well as a number of astonishing excerpts from his singular oeuvre. While I doubt that it will spur a reexamination of his work or inspire a quirky biopic, it does offer viewers an eye-opening look into one of the weirder and darker corners of cinema history.

As a further boon to Milligan scholars, the fest additionally presented screenings of two Milligan features that had been thought to be lost for many years: 1967’s “The Degenerates” (a post-apocalyptic chamber drama in which three soldiers happen upon five women living in a farmhouse and things quickly go sideways) and 1968’s “Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me!” (a frustrated housewife makes a play for her inattentive husband’s best friend and things quickly go sideways). While these showings may not have had the cachet of the fest’s other retrospective screenings of such classics as “Casino,” “Best in Show,” or “Shivers,” my guess is that no one who attended these will ever forget them, no matter how hard they may try.

Not surprisingly, New York itself was a central feature of a number of documentaries in the lineup, led by “Sixth Borough,” Jason Pollard’s engaging and exciting look at Long Island’s often-overlooked contributions to the rise of hip-hop culture through the work of such local heroes as Public Enemy and De La Soul, who used their music to both celebrate and critique their experiences growing up there. Somewhat less enlightening was Josh Swade’s “Empire Skate,” a somewhat glib examination of the city’s skateboard culture as it grew in the ’90s, as seen through the perspective of the celebrated skater brand Supreme. Produced by ESPN as part of their “30 for 30” series, the slickness of the film too often seems at odds with the world it is trying to celebrate.

That said, “Empire Skate” feels like a Frederick Wiseman epic in comparison to the likes of Matt Tyrnauer’s “Nobu” and Greg Oliver and Karin Raoul’s “Raoul’s: A New York Story,” films about two of the city’s dining institutions that feel more like extended commercials than legitimate films especially in the case of the former, which is co-owned by festival co-founder Robert De Niro, who makes several appearances during its running time. Of the two, “Raoul’s” may be slightly better as some of the stories told during its duration are a little more interesting, but in either case, they will leave viewers hungry afterwards for a good meal and a better film.

There were also several films touching on LGBTQIA+ issues, both past and present. On the historical side, Daniel Junge and Sam Pollard’s uplifting documentary “I Was Born This Way” recounted the story of Carl Bean, who fled a childhood marked with abuse to make it as a singer, first as a gospel performer and later with the 1977 gay anthem “I Was Born This Way” before shifting gears in the 80s by responding to the growing AIDS crisis by forming the Minority AIDS Project and the Unity Fellowship Church to minister to LGBTQ+ people of color, through animated interludes and interviews with the likes of Billy Porter, Lady Gaga, Dionne Warwick and Bean himself.

Even more powerful is “Just Kids,” Gianna Toboni’s alternately angering and heartbreaking look at three transgender kids and the specific ways in which their lives are thrown into upheaval by the draconian laws against gender-affirming care. (These laws, it must be said, being instituted throughout the country by people who would never have the spine to watch this movie.)

Likewise, Chase Joynt’s “State of Firsts” follows Delaware politician Sarah McBride on her campaign to become the first transgender person elected to Congress and, following her convincing victory, the appalling treatment she receives from MAGA slime like Nancy Mace who cheerfully go about enacting bathroom bans explicitly aimed at her and misgendering her at every opportunity. These moments are enraging, of course, but they don’t wind up overwhelming things thanks to the perseverance on McBride’s part that Joynt wisely allows to take center stage.

Of all the documentaries that I saw, there were three that really stood out for me and which you should put on your radar. Zippy Kimundu’s “Widow Champion” unveils how in areas of rural Kenya where tribalism and patriarchy still rule, widows are often cruelly dismissed and booted off of land that they should rightfully inherit by their former in-laws and how one woman, Rodah Nafula Wekesa, a widow herself, has taken on the task of mediating between the parties in order to bring peace and justice to both sides while recognizing both the old and new ways.

Ole Juncker’s “Take the Money and Run” takes one of the weirder art-related stories of recent years—having been loaned an enormous sum of money as part of an museum installation revolving around economic inequality, Danish artist Jens Haaning instead only presented two blank canvases and refused to return the money, suggesting that this act was itself the work—as a way of exploring issues of creation, ownership and authenticity that become all the more complicated when they become the focus of the inevitable legal ramifications of his act.

The real jaw-dropper, however, is Suzannah Herbert’s “Natchez,” which explores the still-unreconciled history of the American South and who should ultimately get to tell its story—those who still cling to the romanticized vision of hoop skirts and lavish plantations or those with a tale that doesn’t quite correspond to those “Gone with the Wind”-inspired fantasies. These issues are represented by a wide array of locals, ranging from a preacher who serves as a tour guide to the area who somehow manages to be jovial without glossing over the realities of what he is showing to his clients to one person who, towards the end, is caught on camera cheerfully saying the kinds of things you would never want to be caught saying on camera.

“Natchez” proved to be the big winner in the documentary section of the festival’s awards presentation, scoring the Best Documentary prize as well as special Jury Mentions for its cinematography and editing.