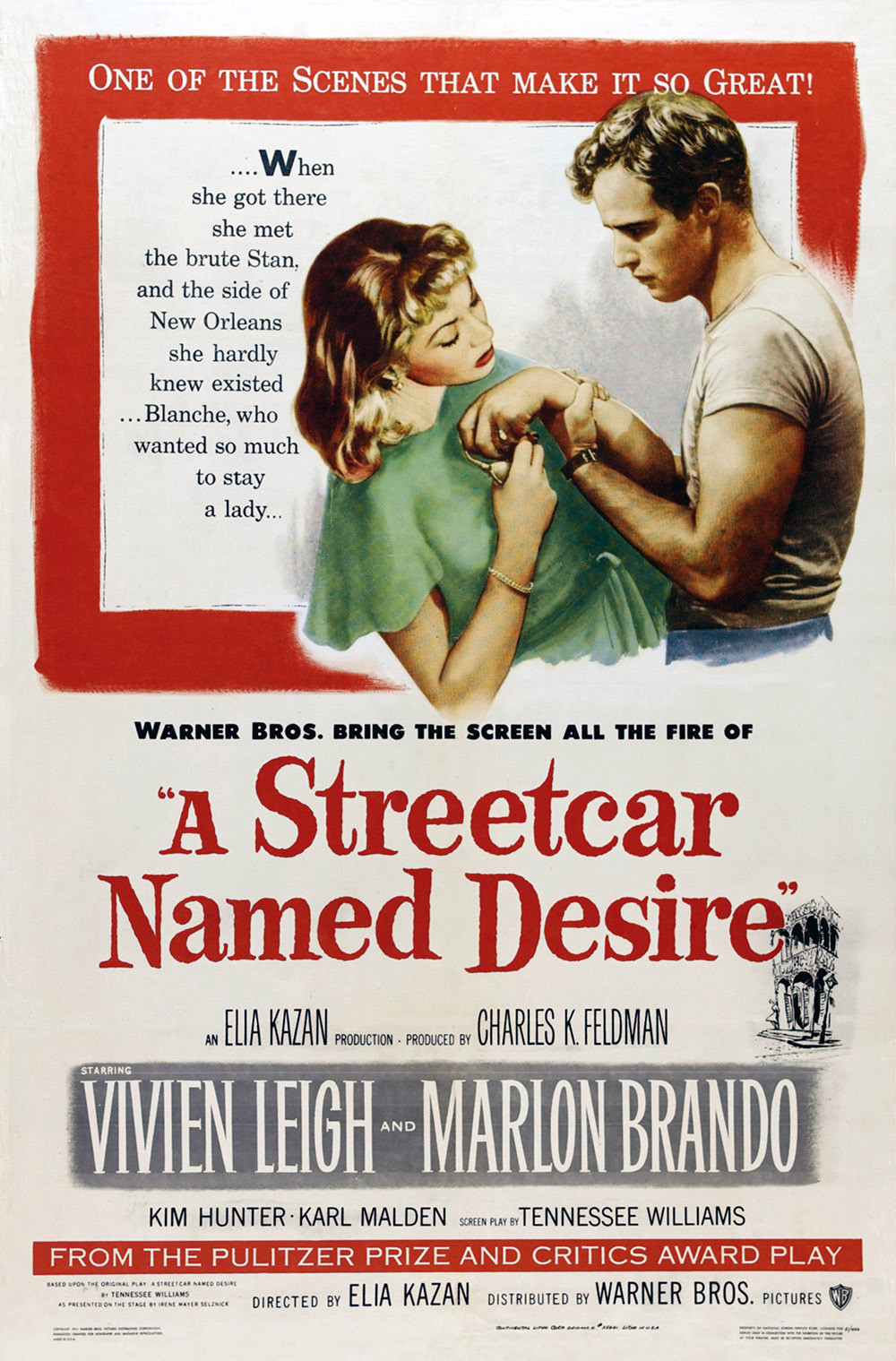

Marlon Brando didn’t win the Academy Award in 1951 for his acting in “A Streetcar Named Desire.” The Oscar went to Humphrey Bogart, for “The African Queen.” But you could make a good case that no performance had more influence on modern film acting styles than Brando’s work as Stanley Kowalski, Tennessee Williams’ rough, smelly, sexually charged hero.

Before this role, there was usually a certain restraint in American movie performances. Actors would portray violent emotions, but you could always sense to some degree a certain modesty that prevented them from displaying their feelings in raw nakedness.

Brando held nothing back, and within a few years his was the style that dominated Hollywood movie acting. This movie led directly to work by Brando’s heirs such as Montgomery Clift, James Dean, Jack Nicholson and Sean Penn.

The film itself, hailed as realistic in 1951, now seems claustrophobic and mannered – and all the more effective for that.

The Method actors, Brando foremost, always claimed their style was a way to reach realism in a performance, but the Method led to super-realism, to a heightened emotional content that few “real” people would be able to sustain for long, or convincingly.

Look at the way Brando, as Kowalski, stalks through his little apartment in the French Quarter. He is, the dialogue often reminds us, an animal. He wears a torn T-shirt that reveals muscles and sweat. He smokes and drinks in a greedy way; he doesn’t have the good manners that 1951 performances often assumed. (As a contrast, look at Bogart’s grimy riverboat captain in “The African Queen.” He’s also meant to be rude and crude, but beneath the oil and sweat you can glimpse Bogart’s own natural elegance.) At the same time, there is a feline grace in Brando’s movements: He’s a man, but not a clod, and in one scene, while he’s sweet-talking his wife, Stella (Kim Hunter), he absent-mindedly picks a tiny piece of lint from her sweater. If you can take that moment and hold it in your mind with the famous scene where he assaults Stella’s sister, Blanche DuBois (Vivien Leigh), you can see the freedom Brando is giving to Stanley Kowalski – and the range.

When “A Streetcar Named Desire” was first released, it created a firestorm of controversy. It was immoral, decadent, vulgar and sinful, its critics cried. And that was after substantial cuts had already been made in the picture, at the insistence of Warner Bros., driven on by the industry’s own censors. Elia Kazan, who directed the film, fought the cuts and lost. For years the missing footage – only about five minutes in length, but crucial – was thought lost. But this 1993 restoration splices together Kazan’s original cut, and we can see how daring the film really was.

The 1951 cuts took out dialogue that suggested Blanche DuBois was promiscuous, perhaps a nymphomaniac attracted to young boys. It also cut much of the intensity from Stanley’s final assault of Blanche. Other cuts were more subtle. Look at the early scene, for example, where Stanley plants himself on the street outside his apartment and screams, “Stella!” In the censored version, she stands up inside, pauses, starts down the stairs, looks at him, continues down the stairs, and they embrace. In the uncut version, only a couple of shots are different – but what a difference they make! Stella’s whole demeanor seems different, seems charged with lust. In the apartment, she responds more visibly to his voice. On the stairs, there are closeups as she descends, showing her face almost blank with desire. And the closing embrace, which looks in the cut version as if she is consoling him, looks in the uncut version as if she has abandoned herself to him.

Another scene lost crucial dialogue. Stella tells her sister, “Stanley’s always smashed things. Why, on our wedding night, as soon as we came in here, he snatched off one of my slippers and rushed about the place smashing the light bulbs with it.” After Blanche is suitably shocked, Stella, leaning back with a funny smile, says “I was sort of thrilled by it.” All that dialogue was trimmed, perhaps because it provided a glimpse into psychic realms the censors were not prepared to acknowledge.

The 1993 version of the film extends the conversation that Blanche has with a visiting newspaper boy, making it clear she is strongly attracted to him. It also adds details from Blanche’s description of the suicide of her young husband; it is now more clear, although still somewhat oblique, that he was a homosexual, and she killed him with her taunts.

Despite the overwhelming power of Brando’s performance, “Streetcar” is one of the great ensemble pieces in the movies. Kim Hunter’s Stella can be seen in this version as less of an enigma; we can see more easily why she was attracted to Stanley. Vivien Leigh’s Blanche is a sexually hungry woman posing as a sad, wilting flower; the earlier version covered up some of the hunger. And Karl Malden’s Mitch – Blanche’s hapless gentleman caller – is more of a sap, now that we understand more fully who he is really courting, and why.

The movie was shot, of course, in black and white. Dramas made in 1951 nearly always were. Color would have been fatal to the special tone. It would have made the characters seem too real, when we need them exactly like this, black and gray and silver, shadows projected on the screens of their own dreams and needs. Watching the film is like watching a Shakespearean tragedy. Of course the outcome is predestined, but everything is in the style by which the characters arrive there. Watch Brando absently scratching himself on his first entrance. Look at the way he occupies the little apartment as if it were a pair of dirty shorts. Then watch him flick that piece of lint.