It’s troubling how simplistic films geared toward teens tend to be, considering that there is nothing simple about adolescence. This year’s Nicholas Sparks adaptation, “The Choice,” infantilized its audience by treating them like a child whose pet lizard had just died. Rather than deal with the difficult questions posed by its own premise, the film whipped out an insultingly artificial deus ex machina in its final moments, rendering the titular choice irrelevant. “The Choice” could’ve easily served as the title for Valerie Weiss’s “A Light Beneath Their Feet,” since its characters find themselves faced with questions for which there are no easy answers. Yet just as Weiss opted for a title more provocative than generic, the film itself is so much deeper than its “teen movie” surface would suggest. The genre staples are all here—mean girls, attractive loners, a song-filled soundtrack, even a prom sequence—but they are all deceptive. There are no heroes and villains or freaks and geeks in this story, just ordinary people struggling to create a sense of normalcy in their day-to-day existence.

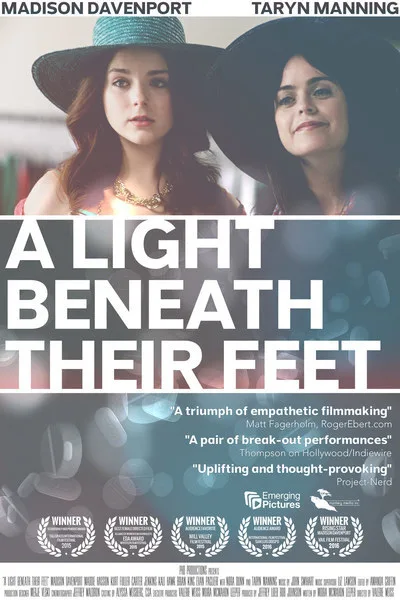

At the center of the film is Beth (Madison Davenport), a high school senior who, like most people her age, is uncertain about her future. Her mother, Gloria (Taryn Manning), was diagnosed years ago with bipolar disorder, which subsequently led to the dissolution of her marriage. “I loved her but I needed to leave her,” explains Beth’s father (Brian King), and his words will resonate with anyone who has ever loved someone with a similar affliction. Unfortunately, his absence from the house has caused Beth to become Gloria’s full-time caregiver, a role that repeatedly threatens to consume the entirety of her life. Though Beth is planning to enroll at Northwestern University, the college located in her hometown of Evanston, Illinois, she secretly yearns to attend UCLA, in part because of the familiar weather patterns on the West Coast. What a rejuvenating change of pace this would provide from the volatile temperature shifts in the Midwest, as well as the volatile emotions at home. The fact that Gloria takes great comfort in her daughter remaining close to home naturally makes Beth all the more reluctant to leave.

Rarely have the dynamics of a loving yet unhealthy relationship been explored with as much tenderness and insight as they are here by Weiss and screenwriter Moira McMahon. The deep and abiding love between mother and daughter is never in doubt, and since Gloria had Beth at a young age, there are moments when the two women resemble twins, particularly in the exquisite shot where they regard their reflections at a clothing shop. Beth laughs at their matching hats and flamboyant poses, but her smile gradually crumbles upon the realization that she’s poised to follow in her mother’s footsteps if she stays fixed at her side. When Gloria insists that she can take care of herself, it is a charged statement, since she has made it explicitly clear that she is staying on her meds solely because it is in her daughter’s best interest. Otherwise, she finds no reason to take pills that dilute her days of vitality. I was reminded of the bipolar couple in Paul Dalio’s terrific “Touched With Fire,” who experience a powerful bond when they go off their meds together, while surrounded by the spirals of light from Van Gogh’s “Starry Night.” One senses that Gloria sees those same spirals as she lies on the floor, staring up at the “stars” on her ceiling.

What Gloria doesn’t realize is that she must be on her meds for nobody but herself if she truly wants to get better. Beth cannot fix her, she can only love her, and love isn’t enough. Cinematographer Jeffrey Waldron finds subtle ways of framing the women in a way that reverses their familial roles, such as when Beth drops Gloria off and waves from the driver’s seat of her car, like a mom wishing her kid a good day at school. The performances Weiss elicits from her two leading ladies are nothing short of sublime. Davenport is adept at conveying tremendous feeling with the slightest flicker of longing or heartache that registers on her face. She’s well-matched with Manning, an actress unafraid of chewing the scenery, as evidenced on “Orange Is the New Black.” Such an approach would’ve been the wrong one for Gloria, and Manning wisely resists any semblance of caricature or crowd-pleasing quirkiness in her portrayal of the character’s manic state. Gloria’s failed attempts at appearing stable while toiling away as a lunch lady, greeting students with overenthusiastic zeal, is painful to watch. She nails the impulsiveness and restlessness that people with bipolar disorder experience, as well as the vacancy in their expressions when their minds are clouded by the haze of illness. Sometimes all you can do as a caregiver is wrap yourself around the person to prevent him (or, in this case, her) from harming himself, and that is precisely what Beth does during an especially frightening episode.

These two people are so compelling and so fully realized that one could imagine a version of the film that was simply about them. Indeed, when Beth and Gloria are together, the rest of the world evaporates. When Beth attempts to remove them from their snug cocoon, suggesting that they dine inside a restaurant rather than order takeout and eat in their car, Gloria stubbornly resists. It is to the credit of the filmmakers that more characters are brought into the story in a way that doesn’t feel forced, and none of them are the clichés they may appear to be at first glance. Beth’s crush, Jeremy (Carter Jenkins), has been deemed a social pariah by his peers, and has resigned to spend his high school days on the outskirts of town, for fear of having to engage with anyone. Some of the film’s most amusing scenes occur at the ice cream parlor where Beth works. As she locks eyes with Jeremy, her smitten co-worker (Evan Paglieri) becomes increasingly jealous, and strives to shield her from a guy he believes is trouble (the way Paglieri softly whimpers, “I love you,” after Beth leaves is priceless). Jeremy’s former lover, Daschulla (Maddie Hasson), is the closest thing the film has to a “villain,” but she’s as wounded as anyone else onscreen, and her actions are ultimately directed at her father (Kurt Fuller), a psychiatrist who pays more attention to his patients than his own daughter. McMahon finds just the right note for each scene, never overwriting moments that could’ve easily dribbled off into expositional overkill. When Daschulla looks at her father and says, “You didn’t do anything,” the line speaks volumes.

“A Light Beneath Their Feet” is a triumph of empathetic filmmaking. It will enthrall viewers merely seeking a coming-of-age yarn, and it contains one of the loveliest prom scenes in recent memory. But for those viewers who, like myself, can personally relate to the story and have been forced to answer the same questions, the film will bring catharsis, tears and perhaps a few epiphanies. I didn’t “get” this film so much as it “got” me.