There is in show biz something known as “a bad laugh.” That’s the laugh you don’t want to get, because it indicates not amusement but incredulity, nervousness or disapproval. John Waters‘ “A Dirty Shame” is the only comedy I can think of that gets more bad laughs than good ones.

Waters is the poet of bad taste, and labors mightily here to be in the worst taste he can manage. That’s not the problem — no, not even when Tracey Ullman picks up a water bottle using a method usually employed only in Bangkok sex shows. We go to a Waters film expecting bad taste, but we also expect to laugh, and “A Dirty Shame” is monotonous, repetitive and sometimes wildly wrong in what it hopes is funny.

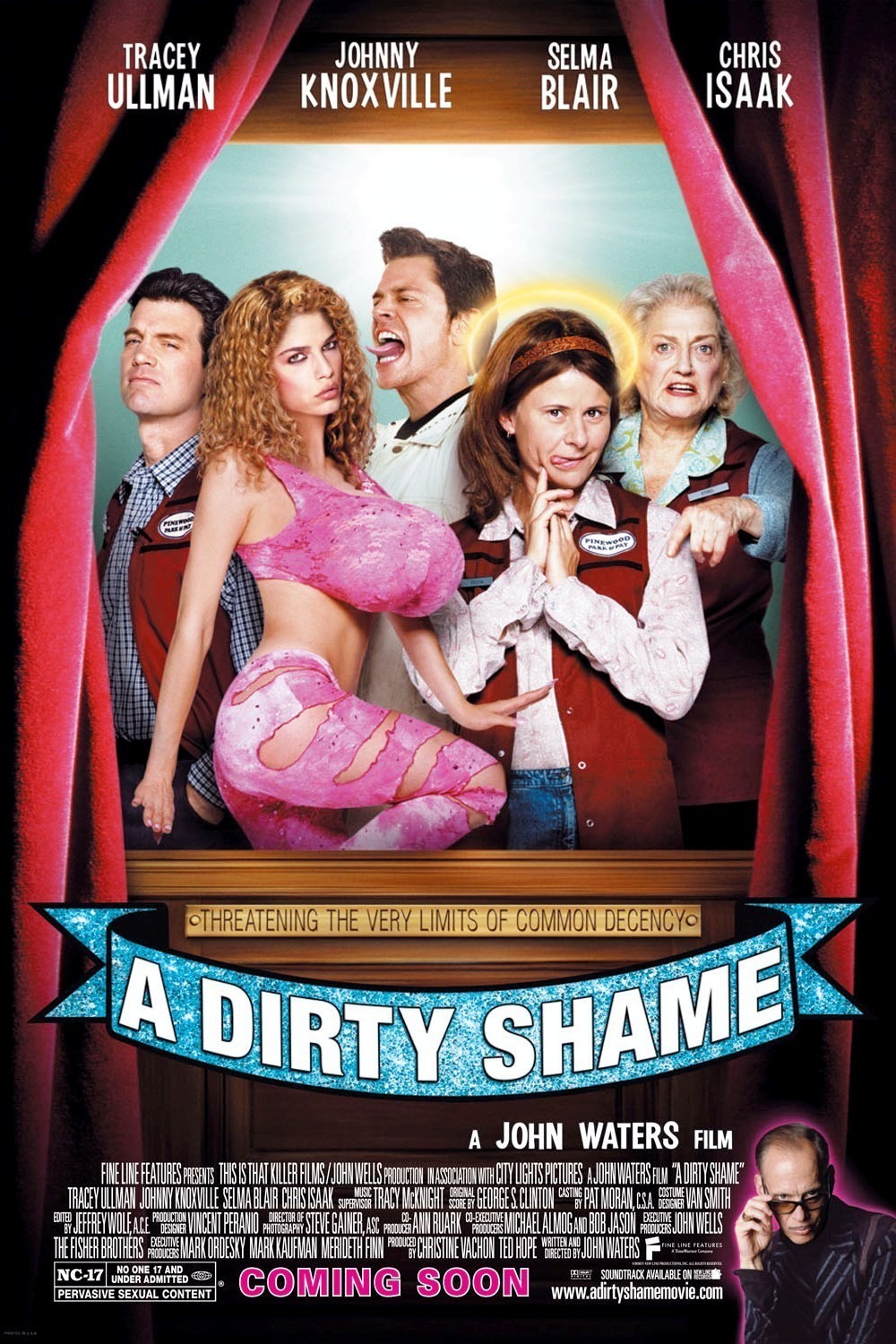

The movie takes place in Baltimore, as most Waters films do. Stockholm got Bergman, Rome got Fellini, and Baltimore — well, it also has Barry Levinson. Ullman plays Sylvia Stickles, the owner of a 7-Eleven-type store. Chris Isaak plays Vaughn, her husband. Locked in an upstairs room is their daughter Caprice (Selma Blair), who was a legend at the local go-go bar until her parents grounded and padlocked her. She worked under the name of Ursula Udders, a name inspired by breasts so large they are obviously produced by technology, not surgery.

Sylvia has no interest in sex until a strange thing happens. She suffers a concussion in a car crash, and it turns her into a sex maniac. Not only can’t she get enough of it, she doesn’t even pause to inquire what it is before she tries to get it. This attracts the attention of a local auto mechanic named Ray-Ray Perkins, played by Johnny Knoxville, who no longer has to consider “Jackass” his worst movie. Ray-Ray has a following of sex addicts who joyfully proclaim their special tastes and gourmet leanings.

A digression. In 1996, David Cronenberg made a movie named “Crash (1997),” about a group of people who had a sexual fetish for car crashes, wounds, broken bones, crutches and so on. It was a good movie, but as I wrote at the time, it’s about “a sexual fetish that, in fact, no one has.” I didn’t get a lot of letters disagreeing with me.

John Waters also goes fetish-shopping in “A Dirty Shame,” treating us to such specialties as infantilism (a cop who likes to wear diapers), bear lovers (those who lust after fat, hairy men), and Mr. Pay Day, whose fetish does not involve the candy bar of the same name.

We also learn about such curious pastimes as shelf-humping, mallet whacking and tickling. As the movie introduced one sex addiction after another, I sensed a curious current running through the screening room. How can I describe it? Not disgust, not horror, not shock, but more of a sincere wish that Waters had found a way to make his movie without being quite so encyclopedic.

The plot, such as it is, centers on Sylvia and other characters zapping in and out of sex addiction every time they hit their head, which they do with a frequency approaching the kill rate in “Crash.” This is not really very funny the first time, and grows steadily less funny until it becomes a form of monomania.

I think the problem is fundamental: Waters hopes to get laughs because of what the characters are, not because of what they do. He works at the level of pre-adolescent fart jokes, hoping, as the French say, to epater les bourgeois. The problem may be that Waters has grown more bourgeois than his audience, which is epatered that he actually thinks he is being shocking. To truly deal with a strange sexual fetish can indeed be shocking, as “Kissed” (1996) demonstrated with its quiet, observant portrait of Molly Parker playing a necrophiliac.

It can also be funny, as James Spader and Maggie Gyllenhaal demonstrated in the film “Secretary” (2002). Tracey Ullman is a great comic actress, but for her to make this movie funny would have required not just a performance but a rewrite and a miracle.

Fetishes are neither funny not shocking simply because they exist. You have to do more with them than have characters gleefully celebrate them on the screen. Waters’ weakness is to expect laughs because the idea of a moment is funny. But the idea of a moment exists only for the pitch; the movie has to develop it into a reality, a process, a payoff. An illustration of this is his persisting conviction that it is funny by definition to have Patty Hearst in his movies. It is only funny when he gives Ms. Hearst, who is a good sport, something amusing to do. She won’t find it in this movie.