“When life turns into death, I’ve seen bodies shining like stars,” says Sandra, who tells her story in “Kissed.” “Each of them has its own wisdom, innocence, happiness, grief. I see it.” From early childhood, Sandra has been obsessed with dead things. She and a playmate would find dead birds and bury them, but then, “after dark I’d go back and give them a proper burial.” In a ritual by flashlight, she rubs her body with the dead bird in what she calls “the anointment.” In her late teens, working for a florist, she makes a delivery to a funeral home, absorbs the atmosphere and states simply, “I’d like to work here.” The mortician is happy to show her around. Opening the door to the embalming room, he says with plump satisfaction, “This is where it all happens.” Soon she is working there.

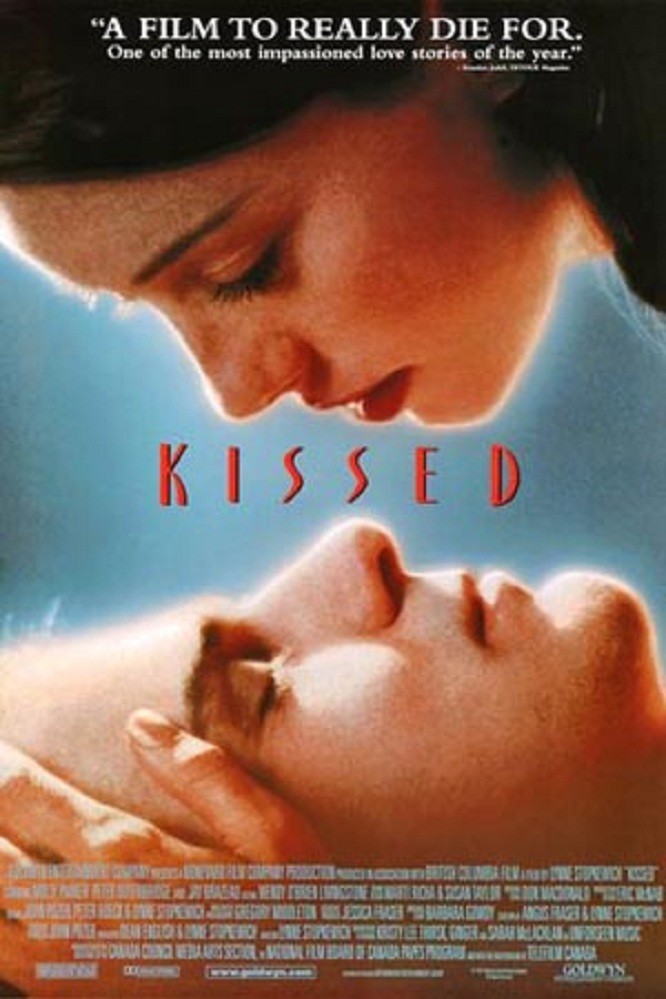

“Kissed” is about a necrophiliac, but in its approach, it could be about spirituality or transcendence. Sandra, played with a grave intensity by Molly Parker, does things that are depraved by normal standards, but in her mind she is performing something like a sacrament. The dead are so lonely. When she comforts them with a farewell touch from the living, the room fills with light, and an angelic choir sings in orgasmic female voices.

“Kissed” was, needless to say, one of the most controversial films at the Toronto and Sundance festivals. Mostly people talked about how Lynne Stopkewich, its co-writer and director, had gotten away with it. One would think there was no way to film this material without disgusting the audience–or, worse, making it laugh at the wrong times. Stopkewich does not disgust, and when there are laughs, she intends them (there is a quiet mordant humor trickling through the film). What is amazing, at the end, is that we feel some sympathy for Sandra, some understanding.

Humans seem to be hard-wired at an early age into whatever sexuality they eventually profess. There is little choice in the matter. Most are lucky enough to fall within the mainstream, but for those who are attracted to obscure fetishes, it is a question of acknowledging their nature, or denying themselves sexual fulfillment. Of course, some compulsions are harmful to others, and society rightly outlaws them; but the convenience of necrophilia, as the joke goes, is that it only requires one consenting adult.

In the case of Sandra, her sexuality seems to be bound up with her spirituality. She feels pity for the dead bodies in her care. Stopkewich makes it clear that sex does take place, but like many women directors she is less interested in the mechanics than in the emotion; the movie is not explicit in its sexuality, although there is a scene about embalming techniques that is more detailed than most of the audience will require. In Sandra’s mind, she is helping the dead to cross over in a flood of light to a happier place: Her bliss gives them the final push.

Then Sandra, who has never dated in a conventional way, meets a young man in a coffee shop. His name is Matt (Peter Outerbridge). She is stunningly frank with him. “Why would you want to be an embalmer?” he asks. “Because of the bodies,” she says. “I make love to them.” He is fascinated. Soon she finds a notebook he is keeping, a sexual journal cross-indexed with obituaries from the local paper.

“It’s not about facts and figures!” she says. “It’s about crossing over.” “I have to do it,” he vows.

“I *need* to do it,” she tells him. “It’s not something you force yourself to do.” If Sandra’s obsession is unnatural, Matt’s is much more common: His male pride becomes involved in pleasing the woman he loves, and he finds himself in competition with the dead. Jealousy drives him–and jealousy’s accomplice, love. But how can he possibly compare with his rivals? “Kissed” is a first film by Stopkewich, who is 32 and lives in Vancouver. Talking about the film at Sundance, she said she read the original story, “We So Seldom Look on Love,” by Barbara Gowdy, in a book of erotica for women.

“It haunted me. Sandra is in charge of her sexuality. Although she is a fringe dweller, she achieves something we all search for. We’re all looking for transcendence.” Oddly enough, this is a feeling the movie largely succeeds in conveying, although there is perhaps an insight in something else Stopkewich said: “At the end of the shoot, every single person working on the film said they would choose cremation.”