True artists can’t be disallowed from expressing themselves, as legendary Iranian director Jafar Panahi has been demonstrating throughout the first half of his 20-year filmmaking ban in Iran. This is partly why even the mere idea of watching a new film by Panahi comes with a certain incontestable gratification. A savvy rebel, he continues to laugh in the face of that sentence and produce one fascinating cinematic oeuvre after another, manipulating and evolving the art form he’s mastered with startling finesse.

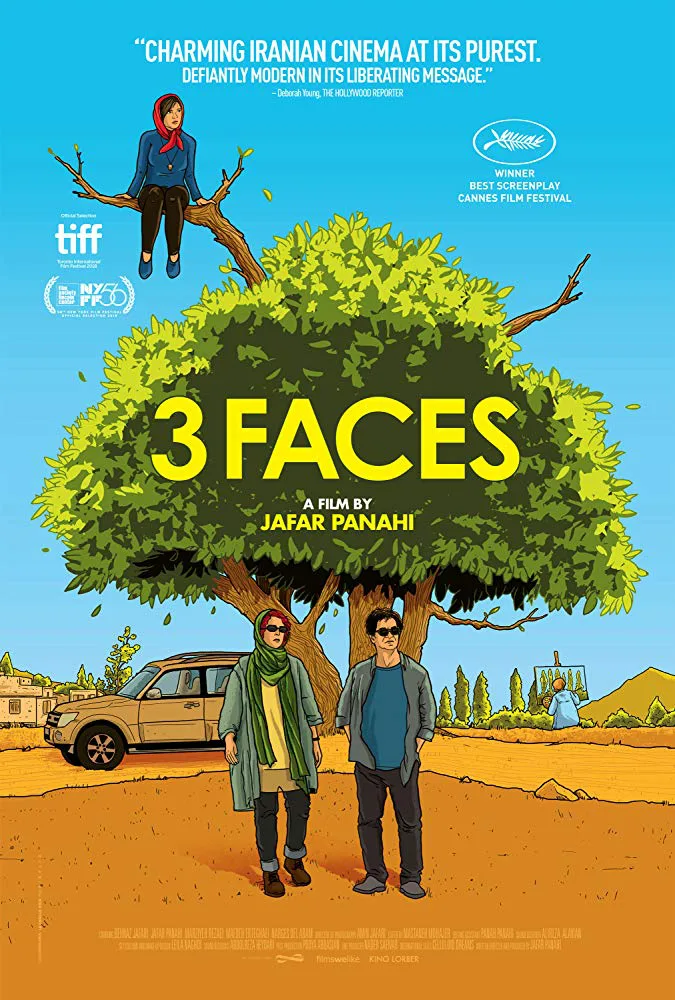

His restrictive era started with the claustrophobic yet thematically expansive “This Is Not A Film” in 2011 and continued with “Closed Curtain” (2013) and comparatively free-feeling “Taxi” (2015). Now he breaks out of his chains once again with “3 Faces,” his fourth feature written and made under the legal bar. While Panahi travels through the countryside and observes more than his immediate reach this time, his latest still fits with the rest of the above-mentioned pieces of the puzzle, even if it’s not the best of them. With “3 Faces,” writer/director Panahi solidifies his artistic handle on his unjust situation by inventing new ways to work around it and remains, more than ever, an effortless blender of documentary and fiction through mystifying methods.

“3 Faces,” in which everyone plays a fictitious version of themselves, starts with a film within a film, shot by the young Marziyeh Rezaei on her cell phone. Marziyeh’s defeated face pleads inside the phone screen with words that sound like a suicidal farewell. Walking and talking frantically, she talks about her broken dreams of becoming an actress; about how she couldn’t study at the prestigious Tehran drama school her heart desired after getting married off by her disapproving family. Addressing her close friend at first, and then the celebrated Iranian actress Behnaz Jafari (whom she apparently tried to contact before to no avail), Marziyeh finally reaches her destination in a cave, puts a noose around her neck and from what we can see, ends her life.

For a film that starts off with an apparent suicide, “3 Faces” unfolds rather whimsically with a serene tempo. Distraught that she wasn’t able to help out this poor, perfect stranger (she says she hasn’t received any of the young woman’s cry-for-help messages on Instagram), Behnaz ditches her professional duties in an ongoing production and recruits her friend Panahi to take a road trip towards Marziyeh’s town in order to solve the mystery of the suicide note. Not unlike Agnès Varda and JR’s “Faces Places,” the duo’s journey weaves together a series of pastoral tableaux, while tipping its hat to various rural Abbas Kiarostami films (such as “Taste of Cherry” and “The Wind Will Carry Us”) that concern themselves with existential matters. Through narrow and winding roads between Turkish-Azeri speaking villages, the pair comes across a wealth of wry-humored idiosyncrasies among town folk who hold on to their traditions for dear life. A shepherd brags about his sick cow’s hard-earned reputation as a stud, an old woman decides to try out her newly dug grave (it sounds grim, but it comes across strangely amusing) and a group of villagers mix the pair up with repair persons, only to dismiss them as “entertainers” with pointed disappointment later on.

That visible annoyance segues into Panahi’s subtle critique of the society’s views on art and the longstanding perspective of women who act for a living. While Panahi works his way towards an eventual (and pleasant enough) resolve for Marziyeh’s mystery, he makes a political and gently feminist statement on Marziyeh and the women that came before her—in fact, the film’s title refers to three generations of female artists in that regard. In addition to Marziyeh and Behnaz, we get to learn a great deal about the iconic pre-revolution Iranian actress, poet and dancer Shahrzad (who famously starred in Massoud Kimiai’s 1969 film “Qeysar”)—she never appears in the movie, but her fall from grace often gets cited by locals as an example of the bleak fate that eventually awaits women of her sort. Gradually, Marziyeh’s troubles assume an even deeper dimension when seen through this context.

Shot by Amin Jafari through a lens that captures dusty, sun dappled hues and endless horizons ahead of narrow rural roads, “3 Faces” resolves to a surprisingly positive, yet open-ended note in its final shot. Panahi can’t help but flaunt optimism wherever he sees it—he lets it rise above it all despite the odds.