Agnes Varda is almost 90 years old and she is still making films. That alone should be cause for dancing in the streets. But wait, there’s more: Agnes Varda is almost 90 years old and she is still making fantastic films. Searching, compassionate, provocative, funny, sad ones. This is one of them. You should see it, and then go dancing in the streets.

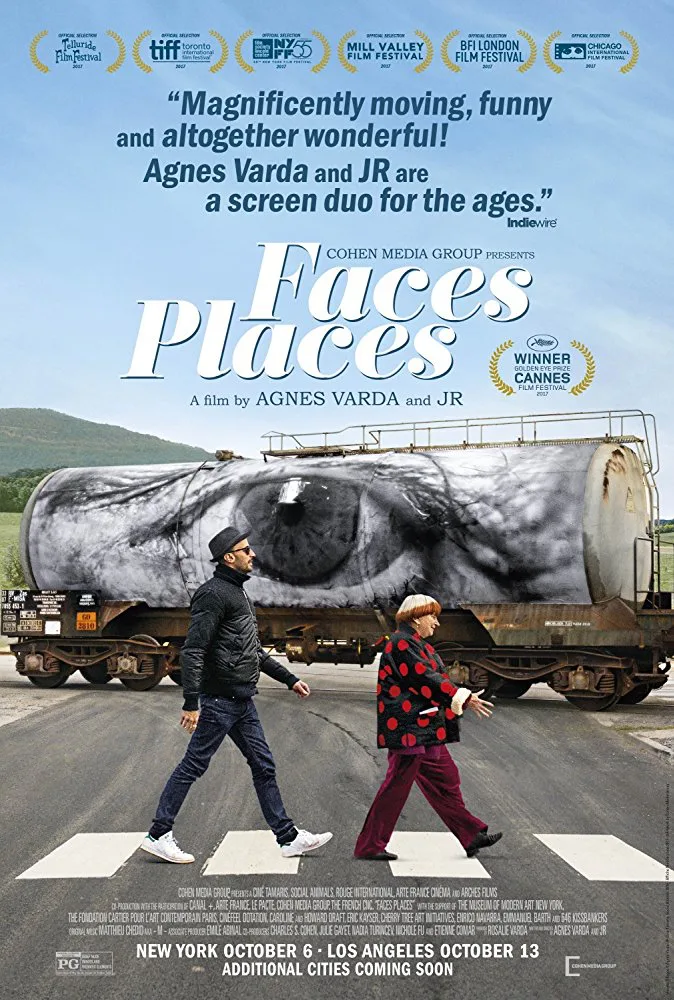

Varda has been making films since 1955, and throughout her career, which saw her as one of the key figures in the French New Wave, she’s been a generous and ingenious collaborator. For this movie, which is part character drama (with real-life characters), part road documentary, and part essay-film, Varda co-signs with the French artist who calls himself JR. A bit over one-third Varda’s age, he always sports a hat and dark glasses. His work is in photography and public art. He travels through Europe in a van that’s a photo booth, creating large-format portraits of people he meets. He goes even larger with some of his other works, creating giant pictures that he then affixes to the sides of buildings, or train cars, or ships. After which he documents that work, and lets nature take its course—the images are generally washed away by time. In this film, one is very dramatically swept off by the tide.

JR’s is a humanist artistic mission; he gets ordinary people to partake in his work, which inevitably delights them. This movie, which has the French title “Visages Villages,” opens with scenes set in various places where, Varda and JR explain in voiceover, they did not meet. (Included is a funny scene at a disco, where a spry Varda—her unusual bowl haircut totally white on top, with a thick ring of vermillion at bottom, a kind of tonsure—dances up a storm at the other end of the floor from JR.) Once each describes the others’ work, and their mutual admiration, they’re off in JR’s van.

Varda’s ideas for photo work bring her to places she visited long ago, and her own earlier films. They visit the village of Cherance, in Normandy, where Nathalie Sarraute, the great writer to whom Varda dedicated her amazing 1985 film, “Vagabond,” lived. They find the well-hidden graves of Henri Cartier-Bresson and his wife, and pay homage. But while they honor the dead, they concentrate on celebrating the living. At one village, they see a row of one-time miners’ houses, waiting to be torn down. The hold up is one woman, the surviving daughter of a miner, who’s staying put. Her portrait, along with vintage images of the miners from the town, is pasted to the houses. The port at Le Havre, a man’s world clotted with ship’s containers, sees its largely unheralded women celebrated with a triptych pasted to a block of stacked containers. An enlarged portrait of Guy Bourdain, a one time collaborator of Varda’s who went on to become a celebrated photographer, is put on a concrete bunker that Germans abandoned in World War II and ended up off a cliff and embedded in a beach. A visit to a goat farm inspires an artwork calling for goats to be permitted to own their own horns.

As they make their way, sometimes merry, sometimes melancholy, a double-portrait of the artists forms. It’s very moving. Varda’s sight, which served her so well so many years, is getting dimmer. At the same time she wonders why JR always wears dark glasses. This habit, she tells him, reminds her of an old friend, Jean-Luc Godard. The resemblance sets up the film’s finale, which is puzzling, heartbreaking, but ultimately celebratory. And wobbles the line between documentary and fiction so strongly that the vibrations will linger in your heart for days afterwards.