This is the second in a series of articles about personal losses suffered in April. To read Part 1, “Hurricane Bettye,” click here.

Because my mom and dad got divorced and remarried when my brother and I were young, we had four parental figures growing up.

Only one was really worth a damn, and that was my stepmother, Genie Grant, who died April 25, 2009, of cancer.

Genie was a singer with a voice modeled on Peggy Lee and Rosemary Clooney—smoky and witty and insinuating but not vampy; not the iron lady or diva or femme fatale in the movie, but the no-nonsense best friend who tells it like it is, with a gleam in her eye. Born in St. Louis, Missouri and raised in Buffalo until age 19, Genie moved to Dallas in 1951, had five children by her first two husbands, then married my dad Dave Zoller in 1986 and acquired two more kids, my brother and myself. She was a dedicated union woman, serving as Secretary/Treasurer of the Dallas/Ft. Worth Professional Musicians’ Association Local 72-147 until her retirement in 1999.

She was short and plump, with apple cheeks and small hands and big forearms. When she moved across the room, you knew she was coming over to talk to you because she locked eyes with you and grinned as she advanced.

“Darlin,” she’d start half her sentences. “Darlin'!”

“Darlin’, listen to me.”

“Darlin’, now listen here!”

“Oh, darlin’—what are you gonna do now?”

Whenever I’d introduce Genie to my friends, I’d say, “This is my stepmother, Genie,” and she’d clarify: “Wicked. Wicked stepmother!”

But Genie was as far from wicked as a person could get.

The only thing wicked about Genie was her wit, which she only deployed against deserving targets.

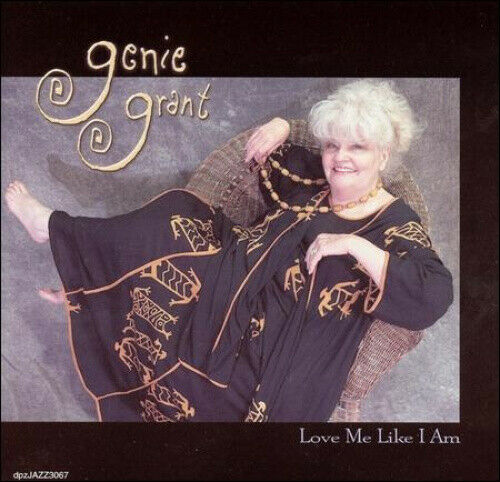

She and Dad were a great team. He produced and arranged and conducted her solo albums as a vocalist. My favorite of these is “Love Me Like I Am,” the cover for which (pictured at the top of this article) sums up Genie’s energy. I love that she’s wearing what she’d wear to a backyard barbecue. She’s not putting on airs. She’s not glammed-up. She’s not selling anything. She’s just Genie. The image is a joke on the seductive “girl singer” photo (as Genie would describe it) and yet, at the same time, sincere: “Damn right I’m fabulous! Just look at me!”

Genie was a model of how to be a sensitive, caring, but non-interfering adult—the kind of person that a child eventually grows out of seeing as an authority figure, and instead treats as a treasured friend and sounding board. When my father, pianist and composer Dave Zoller, died last year at 78, there was nothing left unsaid between us. It was the most altogether positive relationship I’ve had with another family member who was not one of my children. I have Genie to thank for that because, as I wrote in this piece about dad, she figured out how to repair the estrangement that had been growing throughout my childhood and adolescence.

Some of it was his fault. By Dad’s admission, he was a guy who probably shouldn’t have had kids when he had them. He was a young man committed to his art. He didn’t have space for much else.

But truth be told, a lot of the angst came from anti-daddy propaganda, fed to me and my younger brother Jeremy by our mother and stepfather for years and years on end. Mom and Bill cultivated an “us against the world” energy that transformed our home, a bungalow near Love Field Airport in Dallas, into a cult compound consisting of four people, plus pets.

My mother Bettye, a singer-songwriter, actress, and voice teacher, had all sorts of issues. As Genie once put it, Mom’s issues had issues. Mom’s second husband, Bill Seitz, was the perfect match for her, and I don’t’ mean that as a compliment. They amplified each other’s most drastic melodramatic and dysfunctional traits. Of course they were madly in love, never more so than when a third party was coming after them seeking redress for some (usually valid) offense, or taking issue with some aspect of their strange and sometimes frightening behavior.

I had insomnia from the fourth grade onward. It started in the summer of 1977, after my stepfather beat my mother so badly that she didn’t work for two weeks because she didn’t want to have to explain the black eyes, split lip and the choking marks around her throat. Much of the time, though, it was Mom instigating violence. She would get drunk and needle and tease and mock Bill, and even throw objects at him, until he’d finally detonate in a rage. There were multiple guns in the house and Bill would fire them into the ceiling, walls and baseboard when he wanted to make a point or “let off steam.” The very first night my brother and I moved into the converted garage that would become our shared bedroom, after five years of being stashed in Kansas City with our maternal grandparents following the divorce, I noted a hole in the ceiling, and Bill explained that he and my mother had a fight a few days earlier, and she wouldn’t stop yelling at him, so finally he fired a .38 revolver over her head to shut her up.

Some day I might need to write a play about the the day in 2005 when Mom and Bill had a drunken confrontation at a Mexican restaurant and Mom locked Bill out of their house. My brother and stepbrother tried to broker a detente. They behaved like adversaries in a preliminary divorce hearing until we broached the subject of the two of them going into rehab for alcohol abuse, at which point they sat next to each other in a tight two-seater couch and started finishing each other’s sentences.

Despite such madness, we were raised to believe Dad was a bad parent, in sad contrast to Bill and Mom’s unquestioned excellence. We were told that Dad was a flake and a pothead and somebody who lived inside his imagination and didn’t have much interest in, or talent for, fatherhood.

All these things were true, but not nearly to the extent that we were led to believe. I later found out that her most scandalous and often-repeated stories about Dad—like how he cheated on her, and that he was so incompetent with money that she’d give him cash to go downtown and pay the electric bill and he’d come back two hours later with a crate full of new albums—were things that Mom had done. (A few months before Mom died, we were talking in the nursing home, and she blurted out, “He slept with anything that moved.” I said, “Dad told me he didn’t step out on you until years of you stepping out on him,” and she laughed and said, “Well yeah, that’s true!”)

We were also told, on more than one occasion, that Dad wasn’t wired right, that he wasn’t capable of love, that there was something wrong with him that prevented him from being a good dad, and that was why he wasn’t around much. With the fullness of hindsight, I now know that things were considerably more complicated than that—and that, like those tales of Dad cheating on Mom, and blowing utility money on vinyl records, there was a lot of projecting going on.

I got my first gray hairs at 12. By 16, I had salt-and-pepper hair, and was going white at the temples.

I took Bill’s last name in high school, in part to assure him and Mom that my allegiance was to them (“Whose bread I eat, his praises I sing” proclaimed a calligraphic card thumbtacked to the cork board over Bill’s desk). I definitely did it in part to hurt my father for not being much of a presence in my life. I didn’t have the guts to tell him, though. He found out at a fundraiser for the family of a musician who died of a heart attack. He was one of the performers. I painted a commemorative portrait of the deceased. When it was unveiled, the guests realized that I’d signed it “Matt Seitz” and gasped.

Dad got drunk at the bar.

Not long after that, Genie called me and said, in so many words, that she was tired of Dad and me not getting along when it was obvious to anyone with eyes and ears that we’d be “thick as thieves” if we could just talk to one another honestly.

I was taken back to be addressed so intimately. I didn’t have much experience around Genie. Jeremy had started spending time over there a couple of years earlier, when I was at college and he was still in high school, but neither of us had logged a lot of time in their house because it wasn’t that kind of parent-child relationship. I liked Genie a lot from the very beginning, even though I didn’t really know her that well, because of how Dad acted once they got together. Dad was a ladies’ man who had a lot of girlfriends, one after the other, in quick succession. He wasn’t a cad or a wolf. He was just good-looking and talented and single and a jazz musician. It was the ’70s. He owned a waterbed. Dad met Genie in 1978 and they became exclusive not long after that because Genie told him she didn’t want to share him with anyone else.

Mom used to make fun of Dad for settling down with Genie. Dad dated conventionally attractive singers and actresses and dancers, women who tended to be curvy or slim and about his age or slightly younger. Genie was a pumpkin of a woman with a big laugh, a big appetite, and zero tolerance for any sort of bullshit. She was also thirteen years his senior. “What does he see in her?” Mom would say. “She’s not a looker. She’s an OK singer but she doesn’t have my range. She’s almost old enough to be his mother. Maybe that’s it? Maybe he needed a mother?” She couldn’t imagine that Dad just dug Genie for all sorts of reasons and wanted to live the rest of his life with her. Mom thought there had to be some mysterious element she was missing, or some kind of subterfuge or false front, or that perhaps Dad was just settling, for reasons that only a therapist could unpack.

What she couldn’t see, or recognize, was that Genie was a healer. She went about her life trying to make things better. Day by day. Person by person. Problem by problem.

There was a distance between Dad and Genie and Jeremy and me that had not yet been closed. Genie’s call to me that day made it clear that she intended to close it.

And so Dad and I met in a public park in Dallas. Neutral territory.

He told me, “You didn’t have to cut my balls off in public.”

Things got messier from there.

But by the end of the afternoon, we were talking again. I mean really talking.

Over time, we became truly close. Genie engineered all of it. Dad and I were in agreement that she was primarily responsible for repairing the rift between us. She did that sort of thing for countless friends and relatives over the decades. She was a diplomat and negotiator, somebody who could stand back and see the big picture and how to improve it.

Genie invited me and Jeremy over for dinners and lunches and weekend visits. We became such regular presences at the house that we began apportioning holidays into sections of the day, to make sure that we gave Dad and Genie a few hours instead of letting Bill and Mom have the lion’s share. This pissed them off. They felt neglected and perhaps betrayed in some way. Who were these interlopers, , taking away their family time with their boys? Where had they been all those years, etc. etc. (Jeremy and I knew the truth now—and so do you).

When I was a freshman in college, I self-published a collection of three short stories. The third, “Clay,’ was set in 1975. It was about a boy who lost his father in Vietnam and seemed to have somehow inherited his father’s rage and PTSD. When another boy comes to him for defense against bullies, he doesn’t just beat them up, he stabs one of them in the stomach with a switchblade and cuts off two of his fingers. Genie called me up after she read it. She said she was worried about me. I said, “Genie, I’m not gonna go postal, don’t worry. It’s a fantasy.”

She said, “That’s not what I’m worried about. I had no idea that you had enough anger and pain in you to produce a story that sad.”

“Well, did you like the writing, at least?” I asked.

“Darlin’,” she said, “It was somethin’ else.”

And I knew she meant it. That was the ultimate compliment coming from Genie. If she liked it, she said it was good. If she loved it, she said it was “out of this world.” But if it moved her, to the core of her being, she’d say, “Now that was somethin’ else.”

That was when I started talking to her and Dad about what was really going on in Mom and Bill’s house, with the drinking, the thrown objects, the beatings, and Bill fetishizing guns and shooting them off inside the house.

I wasn’t living there anymore and Jeremy was just about to go off to college himself, so there was no point calling the police on them. They’d have just closed ranks anyway and deny anything untoward had occurred. But the stories deepened their appreciation for what Jeremy and I had been through. It also gave Dad feelings of guilt that persisted throughout the rest of his life, despite my and Jeremy’s assurances that we forgave him for not being there, and for not knowing.

Again, this is all messy stuff. There are no easy answers in situations like this. The point of my sharing it is by way of insisting that, in the end, I believe it’s better for families to have the full stories about each other than live with lies, half-truths, evasions and omissions.

Genie taught me that.

Genie was—and I don’t use this word lightly, because so many self-serving narcissistic charlatans claim it, and devalue it— an empath. Truly an empath. She could sense stirrings in the Force, so to speak. There were times when my brother or I were upset about something—”girl problems,” a lost opportunity, a professional setback, you name it—and we’d get a call out of the blue from Genie, just wanting to see how we were doing. She always seemed to call at the precise moment that we needed someone to talk to.

I often got the impression that Genie served as a model for Dad in being a parent. He was certainly a loving and involved parent to Genie’s children, who were in junior high and high school when they first got together. Jeremy and I often discussed the question of whether Dad was always a good parent but never really got a chance to show it to us, or if he learned from being around Genie. Probably more the latter. Or, to be more precise, maybe being around her awakened something in him that would’ve stayed in hibernation if he’d remained married to Mom, or if he’d stayed single or married somebody different.

In my junior year at Southern Methodist University, I got a job recording every word in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary for a series of ESL tapes (long story, some other time) and called Dad to ask if I could come over to his house to do the recordings because the college apartment complex was too noisy. This was not true. The apartment complex was only noisy on weekends. What I really wanted was an excuse to move in with Dad for a while, just to see how it felt. It felt great. We sat up late watching movies, and I got to listen to him practice piano, something I hadn’t gotten to do since I was six.

Genie found my mother’s indestructible crush on Dad hilarious. Sometimes she’d treat it as a spectator sport. One time my first wife and I went to lunch with Mom and she got drunk on margaritas and insisted that, instead of dropping her at home before going to Dad’s house, she’d come along with us. Jen and I thought that was absurd and potentially disastrous, but he was adamant and insisted she’d be on her best behavior. I called the house and Genie answered. I told her what Mom said, and she laughed and said, “Sure, why not. Let’s add one more clown to the clown car.”

When we arrived at the house, Dad was sitting in the backyard in a wrought-iron chair at a small wrought-iron table, drinking iced tea and reading the New York Times. Clearly he wanted to make sure that whatever was about to happen didn’t happen in the house. Genie later said it was as if Dad was trying to lure Godzilla out to sea, so that he couldn’t flatten Tokyo.

Mom, who was still snockered from lunch and had somehow convinced the bartender to give her one more margarita in a plastic “To Go” cup, stumbled through the front door, breezed past Genie and her tiny yapping dogs, made a beeline for Dad in the backyard, plopped down across from him, and cranked the flirting dial up to 11. Genie and I and Jen watched through the glass patio doors.

“I’m getting a Miss Piggy and Kermit feeling here,” said Jen, watching Mom gesticulating and fidgeting and throwing her head back to roar at statements my Dad made that were almost certainly not intended as jokes.

“Miss Piggy had more dignity,” Genie said. “But what can she do? David put a spell on her almost forty years ago, and it’s never subsided.”

“Does it ever bother you that Mom is still in love with Dad and falls all over him in situations like this?” I asked.

“Oh, heavens no,” Genie said. “He’s embarrassed for her. He’s not gonna do anything. I think it’s a hoot. Watch this—she’s gonna go for the knee.”

A few seconds later, Mom went for Dad’s knee.

“Told you,” Genie said.

My fondest memories of Genie are of her and Dad performing together at jazz clubs around Dallas. They had a marvelous chemistry. They’d pretend to bicker and needle each other, but they were self-deprecating as well, carefully setting up moments where each could profess sincere affection for the other.

When Jen died in April, 2006 of an undiagnosed heart ailment, Dad and Genie were there for me emotionally in ways that Mom and Bill could never have been. Genie especially. Dad and Genie made several trips to New York to check in on me and children, Hannah and James. I still have vivid memories of their first trip a few days after Jen’s death: Genie banging around in the kitchen, whipping up a meal grand enough to feed ten people, while Dad was in the bathroom on his hands and knees with a scouring pad and Ajax, scrubbing the tub and tiles because he couldn’t stand the thought of company seeing it in such a “filthy” condition.

I grew even closer to the two of them, and briefly considered relocating to Dallas to be closer to them, and to have help raising the kids. But in November, 2008, Genie was diagnosed with cancer. It was an insidious variety, in that it seemed to be intelligent, to move when spotted or tracked. They found it on her liver, then it disappeared after chemo, then reappeared on her large intestine, then disappeared again, then settled on her stomach, then spread again to her liver. Then it metastasized. There was nothing doctors could do. To cut out the cancer, they would have had to remove half of her digestive and excretory system. She died the following spring. April 25, 2009.

It was one of the most devastating deaths I’ve witnessed, and by this point I’ve witnessed plenty. There’s something particularly unnerving about seeing a woman who was known for being hearty and full of life being physically reduced, denuded of her essence, evaporated, week after week, month after month.

At the end, she was barely recognizable as herself—as frail as my maternal grandmother, who died of bone cancer in 1985.

I learned from Genie’s daughter Robin how to be an attentive caretaker to somebody with cancer. Near the end, Robin was there at the oncology ward every day. I was there the day Genie died. Robin was by her side, along with Dad, feeding Genie ice chips and sips of water.

Genie’s death brought my father and I even closer together, because we’d both lost mates in April, two days apart. Jen’s death had occurred on April 27, three years before Genie.

I think about those final days often, especially when April rolls around.

“You can let go now, Mama,” Robin told Genie, on the day that they pulled the plug. Genie was long past being able to respond to her. But Robin told me she believed that he mother could still hear her, so she talked to her and touched her face and smoothed her hair.

You can let go now, Mama.

In 2001, eight years before she died, Genie received the first “Jazz Artist of the Year” Award by the Sammons Center for the Performing Arts, the prime spot for local celebrations of excellence in the field. Genie was the first honoree because she was a local legend, and because she was a pioneering and veteran officer in the union, and honestly, there was nobody better suited. To get that award, you have to be great at what you do, and loved by all. Genie was both.

Darlin’, she was something else.

Dad thought so, too.

He wrote a song about her.

Titled, appropriately, “Love Song to a Genie.”

<span id=”selection-marker-1″ class=”redactor-selection-marker”></span>