Editor’s note: The following is a reprint of a 2002 Star-Ledger profile I did of the influential documentary filmmaker Albert Maysles, who died last week at 88. It is not available online. The preceding year, Maysles had won the cinematography prize at the Sundance Film Festival for shooting “LaLee’s Kin,” a film by Maysles, Deborah Dickson and Susan Froemke about the legacy of cotton farming in the American south. I’d spoken at some length to Maysles at an HBO party a couple of weeks earlier, in advance of the movie’s cable debut, and he invited me to visit the headquarters of Maysles Film, then located in midtown Manhattan. I spent a few hours there, and while this reported feature gives a sense of what it was like, I wish I’d saved the entire tape.—Matt Zoller Seitz

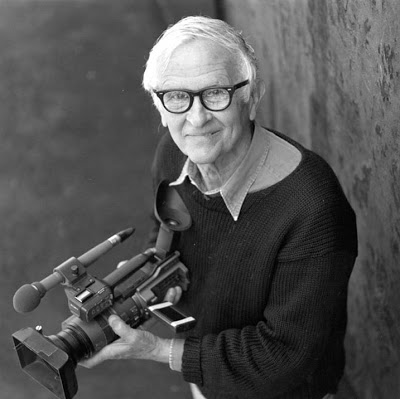

FOR ALBERT MAYSLES, life is an accident waiting to be

filmed. So, of course, he goes looking for accidents.

“Orson Welles once said to me, ‘What is film but a

series of divine accidents?'” recalls the skinny, bespectacled,

75-year-old filmmaker, interviewed last week in the memorabilia-strewn Midtown

Manhattan headquarters of Maysles Films. “The director’s role lies in

noticing what’s going on around him – things that other people see but don’t

catch on to.”

That’s not a bad way to describe Maysles’ way of making

movies.

In the ’60s and ’70s, the Maysles brothers helped pioneer

what is now called “Direct Cinema.” That means a nonfiction film that

has no narrator or host and is less interested in politics than people.

Maysles Films has released about three dozen documentary features

since its founding in 1957. The company’s short list of classics includes

“Meet Marlon Brando” (1965), a sketch of the method-acting icon

during a rocky career patch; “What’s Happening: The Beatles in the

U.S.A.,” about the British rockers’ first visit to the States;

“Salesman” (1969), a meticulous, haunting portrait of

door-to-door-salesmen; “Gimme Shelter” (1969), about the infamous

Rolling Stones concert in Altamont, Calif., and “Grey Gardens”

(1975), a portrait of two eccentric female cousins on the fringes of the

Kennedy clan.

To pay the bills, the company also makes corporate films and

commercials. It is a for-profit company that operates like a collective.

Some films assign director credit to Albert and David (who died of a stroke in

1987), others just to Albert, still others to the Maysles and one or two key

collaborators – an editor, a co-producer, anyone who made a profound

contribution. The company’s most recent effort, “Lalee’s Kin,” is

co-credited to Maysles and two longtime Maysles Films employees, filmmakers

Susan Froemke and Deborah Dickson.

Early on, the Maysles brothers divvied up the work and the

credit. Albert ran the camera, shooting his subjects with a zoom lens from

across the room; David did the sound, often with a shotgun microphone. They

worked this way to give their subjects enough space to be themselves. The

process generated mountains of footage, most of which was discarded during

editing, leaving hard, sharp, offhand details arranged with affection but

without judgment.

In essence, the company makes collages of life – a

comparison that is borne out by a visit to the office, whose walls are covered

with ragged, faded, strangely haunting photo collages by David Maysles.

Direct Cinema is not as well-known as another influential

mid-century film movement, the French New Wave, but it was arguably just as

important. The Direct Cinema filmmakers – whose ranks include D.A. Pennebaker

(“Don't Look Back“) and Frederick Wiseman (“High School“) –

revolutionized how movies were made.

These mostly young directors built new hand-held 16mm

cameras with synchronized sound and special attachments that let filmmakers

mount a battery on the back of the camera, allowing the crew to follow their

subjects anywhere. The filmmakers weren’t worried about getting pretty shots;

if a subject said something interesting in a room with dim lighting, they would

use the moment anyway. “In cinema, production value isn’t everything,”

says Maysles.

As if to prove he’s not kidding, he later leads a reporter

to a poster on the wall that collects 100 small portraits of American

cinematographers, part of a 2000 tribute by Kodak. Maysles locates his own

portrait among the 100 and asks, “Notice anything about this

picture?”

When no answer is forthcoming, he grins and says, “It’s

the only one on the poster with bad lighting.”

Extending the form

Maysles is being self-deprecating. In “LaLee’s Kin” – a searing look at the effects of cotton farming on generations of

African-Americans in Mississippi, co-directed by Froemke and Deborah Dickson –

there are lovely pictorial shots of cotton fields at dawn and dusk. Yet when

the story moves inside, talking to poor, often unemployed people in trailer

homes, Maysles records their cluttered lives and weathered faces with curiosity

and respect, returning some of the dignity their lives stole from them.

Last year Maysles, who photographed about 80 percent of the

film himself with a 16mm camera, was awarded the cinematography prize at the

Sundance Film Festival, the first time in the festival’s history that the award

was given to a documentary.

“In various ways, I’ve been trying to extend the

documentary form,” says Maysles. He compares Direct Cinema to a similar

movement that was happening in print, the Nonfiction Novel – an offshoot of the

so-called New Journalism, practiced by the likes of Tom Wolfe, Truman Capote

and Norman Mailer. In both mediums, the storyteller tried to notice as many

details as possible while appearing to fade into the woodwork.

Direct Cinema often captures uneventful moments, and it is

equally interested in unhappy and happy characters. The people in “LaLee’s

Kin” live lives of desperation, but they also enjoy themselves and their

friends and family, and the movie makes sure we see that.

Maysles and his brother pursued a similar strategy in

“Grey Gardens” (1975); the women gave the filmmakers such access to

their chaotic lives that the Maysles were accused of exploiting the mentally

ill. The only way to get around such criticism was by portraying the sisters as

miserable. The Maysles wouldn’t do it, because it didn’t feel true.

“I like to show people functioning in fairly normal ways,”

Maysles says. “It seems like you’re always having to look at families

killing one another. It’s like people are following Tolstoy’s misguided

statement that all happy families are alike in their own way, but every unhappy

family is different. That makes people conclude, ‘Well, why bother with the

happy ones?'”

Maysles Films is one of the happy families. The company has

had the same name for 45 years and the same office for 20. It has employed the

same key people since the 1970s; many had never made films until they got jobs

there.

Says Froemke, who started out at Maysles Films as a temp

secretary, “The Maysles never wanted to hire anybody who went to

film school. They wanted people who were interested in people, and in everyday

life.”

The list of people who once worked for the Maysles reads

like a Who’s Who of modern documentary cinema – Barbara Kopple (“The

Hamptons”), Bruce Sinofsky and Joe Berlinger (“Paradise Lost: The

Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills”) and longtime employee Dickson, who

just finished a portrait of novelist and social critic Gore Vidal for PBS’

“American Masters.” “Everybody we hire wants to be a filmmaker,”

Froemke says. “We like that. We like to nurture young, up-and-coming

filmmakers.”

Maysles is 45 years past being labeled an up-and-comer, but

there is still something impetuous, even adolescent, in his energy. When he

gives a guest a walking tour of the office’s many framed photos of the Maysles

on location, he makes sure to point out ex-girlfriends. Unlike many veteran directors,

he isn’t threatened by the digital revolution. He adores the portability and

convenience of video and swears he will never shoot on film again; his reasons

are summarized in a photocopied manifesto he hands out to visitors.

He works on two or three movies a year. He never knows where

the next idea is coming from. Sometimes he just hops on a plane and visits

another city or country, looking for a new character, a fresh narrative. For his next project, tentatively titled “Lifetime

Stories,” Maysles will ride trains in six countries, armed with a small

digital video camera, meeting people at random and talking with them. “In

each country, hopefully I’ll find one person with a story good enough that

it’ll make me want to get off the train with them.” [Ed: Maysles didn’t get around to making “Lifetime Stories,” but he did direct or co-direct seven more features after this conversation.]

“You have to rely on luck to be a documentary

filmmaker,” Froemke says. “I think Al’s a very lucky guy.”

She thinks for a moment, then says, “There’s a lot of

luck that happens when you’re working with Al.”