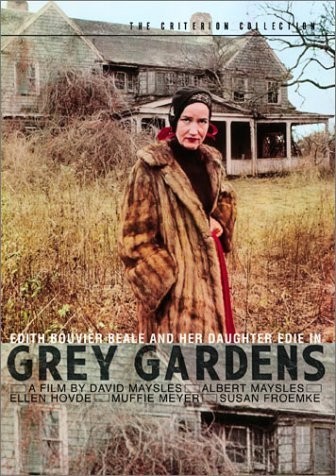

Edith Bouvier Beale sits on her bed, wrapped in a housecoat, surrounded by cats, singing in a reverie: “Tea for two, and two for tea. . . .” And we wonder if it occurs to her that the song is the story of the last, long chapter of her life. For more than 20 years, she and her daughter, Edie, have lived together in a crumbling old mansion by the sea. They are surrounded on both sides by the summer homes of the wealthy – of people from their class — but Grey Gardens stands in Gothic decay.

The house was beautiful once, and so were the Beales. They look through old scrapbooks, this woman of 82 and her 56-year-old daughter, and we see them when they were the cream of society. Edith on her wedding day. Edie modeling at a charity fashion show. Now a slow disintegration has set in; rooms of their mansion and areas of their lives have been closed off, one at a time, left to the forages of raccoons and memories.

Still, they’ve preserved a few things, while abandoning so much. They still have wit, style and what I would define as sanity. “Grey Gardens,” one of the most haunting documentaries in a long time, preserves their strange existence, and we’re pleased that it does. It expands our notions of the possibilities. It’s about two classic eccentrics, two people who refuse to live the way they’re supposed to, but by the film’s end we see that they live fully, in ways of their own choosing.

The film was made almost by accident. Albert and David Maysles, the directors of such documentaries as “Salesman” and “Gimme Shelter,” were approached, by the two Bouvier sisters, Jacqueline Onassis and Lee Radziwell. Would the Maysles like to make a movie about the Bouviers? They might. Jackie and Lee supplied them with information about the family, including their two reclusive cousins in East Hampton, NY The Maysles shot, on and off, for several months. Then they reviewed their footage and decided there wasn’t a movie in Jackie and Lee – but there seemed to be one in Edith and Edie.

They went back to Grey Gardens and all but moved in for two months, using portable cameras to follow the Beales in their daily routines. Many of the routines seem intended for the stage, Mrs. Beale, once a highly regarded concert singer, sings several songs for them. Edie, who’d always dreamed of a career as a dancer, improvises a soft shoe to the Virginia Military Institute fight song. And the two women, in ways that have been exquisitely refined over the years, fight a little among themselves.

It is here that the film has its fascinating, mysterious center, We gradually realize that these two women are absolutely dependent on one another; that they form a composite personality (or, as the Maysles put it, a “closed system”), Edie never married. She brought a few boys home, but her mother didn’t like them. So that’s one thing to fight about. “That was just after the fall of France,” Edie says at one time, dating a memory. “France fell,” her mother says, “but Edie didn’t.” The house is surrounded, as Edie observes, by a “sea of green.” The grounds have grown wild. “I lost a lovely blue scarf in there one day and never found it again,” she muses. Inside, plaster is crumbling from the walls, and raccoons coexist amicably with the Beales and a large family of cats. Old phonograph records are played once again, and on Sunday night the girls tune in Norman Vincent Peale from New York. “First, think,” he advises. “Then, try . . .”

Edie dresses up in bizarre costumes. She likes to wear skirts upside down. She is never seen without a turban. She dresses in lace curtains, in bedspreads, in bathing suits that were last seen on the cover of Life, circa 1948. She and her mother talk all the time, sometimes at the same time — they both know all the words. And out of this existence comes a movie that, curiously enough, is comic and bright, as well as sobering. It’s hard not to find these two odd women likable.

Moments: Edie feeding the raccoons a loaf of Wonder Bread. Edith placidly observing that a cat is defecating behind her portrait. Edie, nearsighted, standing on a scales and reading her weight with binoculars. Edith confessing that she can’t turn around just at the moment because her bathing suit has no back. The two women at night, alone in their room, the crumbling mansion extending around them, listening to old songs and replaying old memories. Me for you, and you for me, can’t you see, how happy we will be. . . .