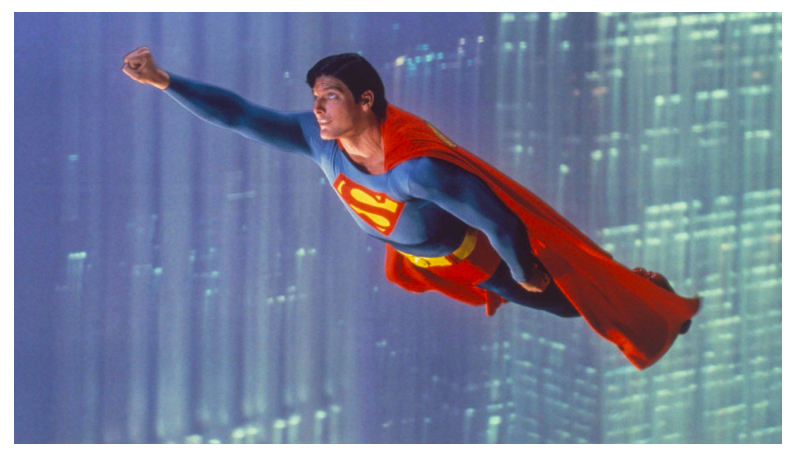

Modern superhero cinema begins with “Superman,” so it’s only fitting that it would kick off with its own version of the Big Bang. It has a momentous quality that somehow never came across as heavy or self-involved. Like Superman himself, it’s denser and more powerful than any superhero film that had been made up until then, yet it still takes off, like a bird, like a plane. It delays its full flight for quite a long time. But when it soars, it never stops.

This was an immense production, supposedly the most expensive American film up until that point, with a lot of creative minds overlapping and reworking one another: Mario Puzo’s 500-page first draft was rewritten by Robert Benton and David Newman, who were rewritten by Newman and his wife Leslie Newman, who were rewritten by Tom Mankiewicz (credited on the finished product as well as on “Superman II” as “creative consultant”). That the result feels as unified as it does is a small miracle, attributable to the steady hand of director Richard Donner and his cast.

Margot Kidder’s Lois Lane is a screwball comedy dame who smokes cigarettes and isn’t shy about asking Superman if his bodily functions are “normal”—a prize-winning reporter and hardheaded career woman whose first line is, “How many p’s in rapist?”, and frankly admits that she never wanted anything like the life of her sister, a suburban homemaker with children. Gene Hackman’s Lex Luthor proclaims himself “the greatest criminal mind of our time,” then nearly proves it, and you believe that he’s really that diabolically brilliant, but also an insecure person who knowingly keeps company with the dumbest henchmen on earth and a girlfriend who tells him every day that she only loves him for his money.

Ned Beatty’s right hand man Otis is a lumbering oaf whose gait earns the tuba melody that composer John Williams saddles him with: he’s like one of those dimwitted cartoon dogs who gets an idea, and the thought balloon over his head contains a birthday candle instead of a lightbulb. Valerie Perrine’s wisecracking moll Miss Teschmacher landed one of the evilest, wealthiest men in the world but seems disappointed at how easy it was, and makes wisecracks about how Lex wooed her with promises of a Park Avenue address but gave her one “500 feet below Park Avenue.” Former child star Jackie Cooper’s Daily Planet editor Perry White gets high on beating the competition: he’s a joyous doodle of journalists who give themselves ulcers trying to live up to a stereotype of the job.

Glenn Ford and Phyllis Thaxter as Clark’s adoptive parents, Jonathan and Martha Kent, are Norman Rockwell characters living in Andrew Wyeth’s waves of grain, but you believe them as people, because you want the world to be filled with people too good to be true, and these two raised Superman, therefore they fit the description. (Jeff East deserves a parenthetical shout-out as well: he might have nailed Reeve’s unaffected earnestness anyway, but Reeve’s dubbed voice and a bit of prosthetic makeup—good enough that in over 40 years, it never occurred to me that it was makeup—puts the gambit over the top.)

First among equals is Christopher Reeve as Superman/Clark Kent, mainly a stage and TV actor when he was originally cast. He beat out countless established stars and delivered the most iconic debut male lead performance since Peter O'Toole in “Lawrence of Arabia.” As Clark Kent and Superman—respectively, a square and a super-square—he held his own with actors who were known, often beloved quantities.

A through-line of unaffected goodness connects Superman’s biological parents, Superman’s adoptive parents, and Superman himself. Reeve understood that Superman wasn’t just a character or a corporate property, he was an idea. And he played the idea in every scene, while still giving you a sense of Superman and Clark Kent as individuals (or the latter as a tamped-down, powerless version of the former). This is a super-being who could’ve been evil, and would’ve have easily ruled the world had he been evil.

But he was raised to be good, in honor of his deeply implanted memories of his lost home planet, Krypton; his posthumous nurturing by his birth mother and father, whose lessons he ingested in the form of recordings en route to Earth; and the Kents, who gave Superman/Clark models of ground-level decency to emulate. Once Superman leaves the nest, he continues to choose to be good, honoring both sets of parents. (Ford’s “You are here for a reason,” followed by his sad/disappointed “Oh, no” as he feels his pulse, is one of the greatest and least-appreciated line readings of that decade: the essence of a man packed into just two words, along with crushing disappointment at the realization that he won’t see anything more.) This Superman is a man on a mission to be America’s (fantasy) vision of itself; or, perhaps more accurately, the incarnation of its best self; or the ideal it strives toward but rarely achieves.

I used to think of Reeve’s Superman as a man with no emotional interior. But watching it again recently I was embarrassed to realize how wrong I was. Quite the contrary: Reeve’s Superman performance is filled with hints that this is a man who knows himself well, such as the way he smiles with amusement and admiration as he looks at and listens to Lois on her terrace, and the moment at the end of that extraordinary sequence (“Can You Read My Mind?”) when he flies off into the night, and the camera slowly moves screen left to catch Clark knocking on Lois’ door, “embarrassed” about having to ask if she forgot about the date she agreed to have with him that night. Superman doesn’t love Lois because he wants to save her. He loves Lois because she doesn’t expect anyone to save her, and because she tries to be as good at her job as Superman is at his. Her love for him is evolved lust plus admiration. His love for her comes out of respect.

Reeve’s Superman exerts great discipline to continue to be a person who inspires, and bases his attitude towards others on how hard they are trying to treat everyone else, especially strangers, as if their lives matter. He has might what we might call a “Jesus gaze”: he forgives them, for they know not what they do. He’s as nice and kind as a super-powered person can be.

Chris Evans’ Captain America, Chadwick Boseman’s Black Panther, and Gal Gadot’s Wonder Woman are the only modern superheroes who get close to the Reeve vibe. They give performances as people who are serene and confident in their goodness. They seem to know that if you can play that kind of energy without winking at the audience to signal that you’re not actually square, it’ll be as arresting as any villain’s scenery-chewing.

Watch how Reeve-as-Superman looks at everyone, really looks at them, really sees them. He seems to feel varying degrees of sadness when he realizes that they’re not there yet, and probably never will be. But you never get the sense that he’s measuring himself against them, finding them lacking, and elevating his own self-image over their existence. He knows this isn’t a contest. There are no winners or losers. Superman only scorns those who aren’t good because they aren’t interested in being good. He hates them not for the bad deeds they do, but their comfort in doing them.

This is why he neutralizes Otis with a look—he knows a guy like this doesn’t deserve worse. And it’s why he reacts to Luthor unveiling his plan with horror and revulsion so primal that he loses his composure, calling out to Eve about the “millions of innocent” people who will die if Luthor detonates a stolen nuclear missile in the San Andreas fault line. Reeve’s choices here are the most daring of any actor in the film, because the rawness of the character’s emotions, and his expression of them, punctures the airy-light tone that Donner has established elsewhere, so decisively that it might never have recovered from the follow-up sequence: Superman, saved by Eve, keeps his word to her by stopping the missile aimed at Hackensack, her mother’s hometown, but arrives in California as the bomb goes off, setting in motion a series of catastrophes that only Superman can avert. Save one: the death of Lois Lane.

The entire performance is a setup for a series of punchlines that could be summed up as, “Yes, he really is that good. It’s not a bit.” And once the punchline lands, the recipient becomes a true believer, sees Superman as representing the best part of themselves, and cheers for him as he does good deeds because his existence is aspirational.

That, I think, is what spurs Superman’s shriek of rage right before he turns back time to save Lois: his disappointment at himself at not being Super enough, and the pain of reliving the death of his father, about whom he said, at graveside, “All those powers. And I couldn’t even save him.” (I can’t have a conversation with anyone who thinks Superman turning back time is “too much,” or “unrealistic”; not only is this a story about a bulletproof extraterrestrial immigrant who can fly, the act itself is a swooningly grand romantic gesture, like something out of a fable: he’s Orpheus descending into the underworld to find Eurydice and bring her back to the world of the living, but he heads in the other direction, out into space.)

But let’s go back to the moment before Superman finally fails, because it’s integral to the goodness of Superman, and “Superman.” After Luthor fits him with a Kryptonite necklace and leaves him to drown in a pool, Eve saves him. Eve’s reaction shots establish that she’s initially impressed by Superman’s handsome face and chiseled physique (as a committed gold-digger would do). Then she immediately figures out that yes, in fact, Superman really is that good, it’s not a bit, he means it. And this leads Eve to measure Lex against Superman and realize that (1) she’s gotten into a relationship that’s entirely superficial, based around money and clothes and jewelry and material goods and proximity to power, and that (2) she did that because she doesn’t respect herself (probably because she’s been with a lot of guys like Lex, though probably without the money); and (3) a guy like Superman will never be within Eve’s grasp because she’s not trying hard enough to be the kind of person Superman would respect.

That moment in the swimming pool is about a character bettering herself after seeing Superman up close. It’s a moment of transformation. She kisses him (against his will, when he’s still powerless) because she thinks she’ll never have another chance with him, or with somebody even remotely like him. She does not, for the most part, respect herself. Which makes that moment where she dives into the water and saves Superman’s life so powerful. We’re seeing Super-Eve: a woman releasing her suppressed potential for goodness.

Reeve’s performance is so strong, in fact, that it validates the boldest storytelling gamble in the movie: we don’t see Superman in costume at all during the first part of the film, save for a glimpse of the character flying away from the newly-created Fortress of Solitude, and we don’t get to the first night of Metropolis heroism until 65 minutes into a two-and-a-half hour running time. It’s the same tactic used in Godzilla movies, horror films, and suspense pictures, but applied to a savior instead of a threat. A film that takes its sweet time unveiling something like King Kong, Godzilla, the xenomorph, the shark in “Jaws,” the mothership in “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” or the title creature of “The Thing” is betting that if they deliver something that’s worth the buildup, the audience will be overwhelmed.

Viewers in 1978 were overwhelmed, and not just because a live-action movie had finally convinced them that a man could fly. They were overwhelmed because Reeve acted the role with so much sincerity that it knocked down their cynical defenses, which is a different sort of superheroic feat. The film’s sense of humor has some “this would never fly today” clunkers, like the black dude with fly threads complimenting Supe’s “baaaad outfit,” and Eve letting Lex pimp her out as bait during the missile theft. And the special effects have dated, as special effects always do.

But the greatest special effect of all, Reeve’s performance, will never date, because it comes from a series of brilliant choices by a self-assured young actor, and thoughtful guidance from scriptwriters and a director who were all on the same page about the most important thing, whatever other differences they might have had during filming.

The movie feels like a case of an entire production rising to the level of its lead actor, who happens to be playing the biggest square in the galaxy, a guy who would rather be decent than cool. This could not have been easy to pull off in the 1970s, a time when antiheroes, cruelty, and cynicism were in vogue, and a public exhausted by nearly two decades of domestic unrest, foreign war, and official corruption had started to think happy endings were superficial and/or a fantasy about what life could be, but isn’t. Reeve’s Superman saved “Superman.” His performance is the reason it still flies.