“Cool Hand Luke” is easy to make fun of because it’s so slick and earnest. It got teased from pretty much the second it hit screens in 1967, and even though it was a hit that won some awards and got nominated for more, it’s still a film that dares to be shrugged off or winked at. Directed by Stuart Rosenberg, from a screenplay by former safecracker and Florida convict Donn Pearce (who wrote the source novel) and Frank R. Pierson (“Dog Day Afternoon“), “Luke” epitomizes an all-but-vanished kind of Hollywood filmmaking: the big-budget art house movie with mythic tendencies. It’s one of the great ones, provided you can meet it on its own terms. I’ve seen it four times since the eighties—one viewing in each decade, now that I think of it—and each time it grows a bit in my estimation. Perhaps this is because the final note is not one of youthful defiance and, well, coolness (qualities that made generations of young men put “Cool Hand Luke” posters on their walls), but a sense of limitedness, even futility, in the face of unchanging institutional power, and a recognition that in a world where bad guys keep winning, if you don’t have dreams and aspirational figures to embody them you might as well crawl in a hole and die.

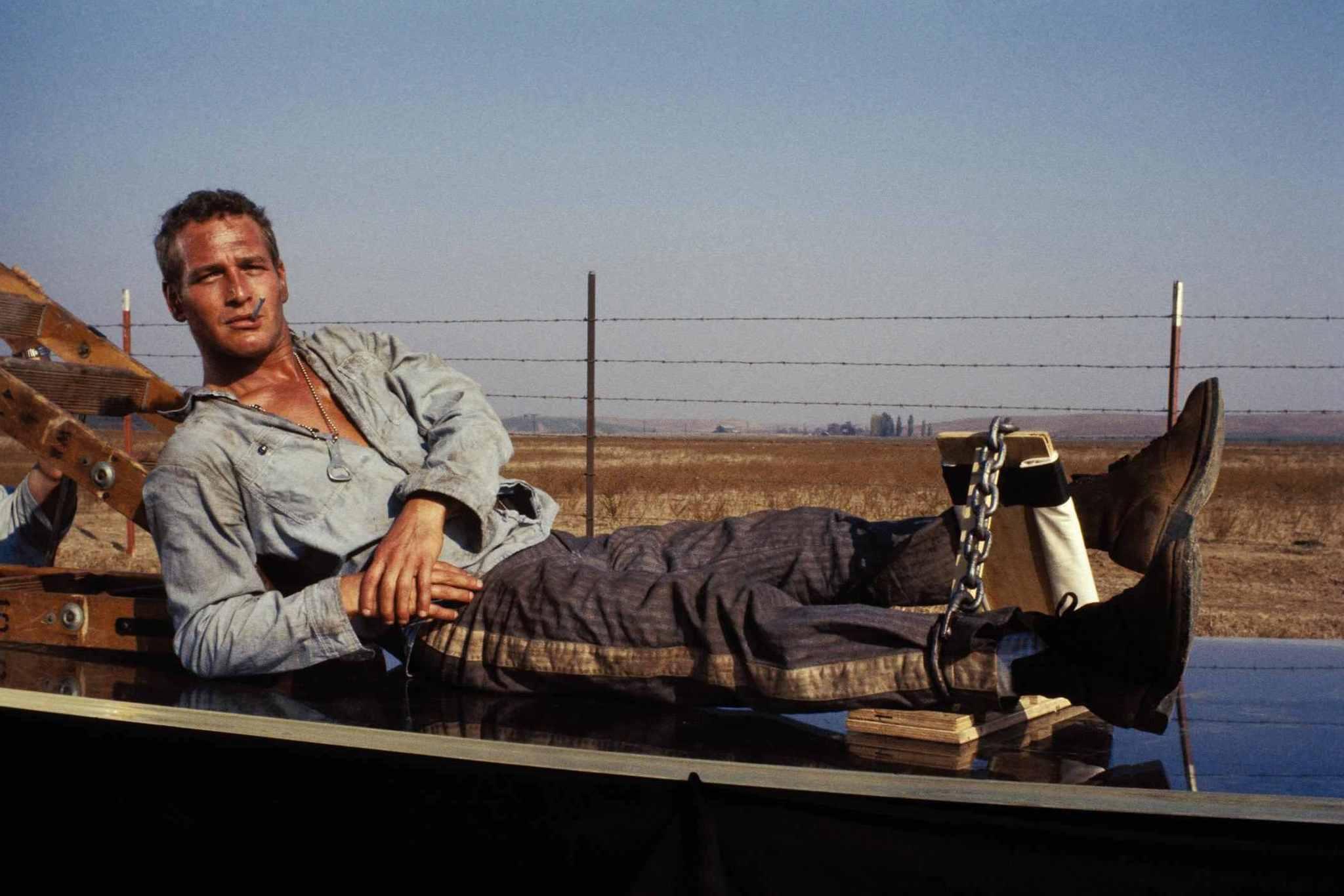

The story is so thin that you have to accept the film at the level of a dream or a fable to accept it at all. Set mainly in a segregated Florida prison in the early 1950s, “Luke” is a widescreen lament, posing its convicts in moving tableaus as they chop away at weeds and help tar trucks seal down roads. Its title character, a disaffected war hero, is first seen cutting the tops off of parking meters; he later says that he couldn’t think of anything better to do in a boring small town. Consigned to a work camp, Luke keeps to himself, reacting more often than speaking. He is often shunted to the corners of frames or into his own closeup, the better to showcase star Paul Newman‘s unmatched ability to push introspection right up to the edge of navel-gazing vanity.

This is no small feat when you consider all the pseudo-Biblical situations and images threaded throughout “Luke” (the title shares the name of one of the books of the New Testament). Newman’s chief rival for big roles during this period was Marlon Brando, and it’s fascinating to imagine what Brando, who’d played many a Christ figure already, would’ve done with such a star-worshiping role; he probably would have been ten times weirder and more off-putting, but probably deeper, and less easy to project upon. (Such a film might’ve been equally homoerotic, though; with its nearly all-male cast full of soulful, shirtless guys caked in sweat, dirt and blood, “Luke” is one of the gayest mainstream Hollywood films of the sixties, and Brando and Dean were rivals in pansexual beauty.)

But it’s the blank slate aspect of Newman’s performance that makes “Luke” almost impossible to resist. There’s a gentleness to him even as he’s smirking and practicing a wiseass’s version of passive resistance, refusing to knuckle under to the whiny hisses of The Captain (Strother Martin), and barely accepting the cold authority of The Captain’s overseer, Boss Godfrey (Morgan Woodward), whose mirrored sunglasses move Luke’s best friend Dragline (George Kennedy) to dub him “the man with no eyes.” The hero is often framed amid bunkmates who eventually come to seem like his disciples or followers. He enters and exits the hole (solitary confinement) while wearing a white gown and waits to be reborn in a few days or a couple of weeks. He partakes in miracles which mingle in the mind with torments, scourging or crucifixions. The famous scene where Luke eats 50 eggs on a dare feels like a bizarre inversion of Jesus Christ’s feeding of multitudes (which appears in all four Gospels) as well as a simultaneously self-exalting and self-punishing communion, with echoes of the traditional Easter egg hunt thrown in for good measure.

In the horrendous near-climax, the escaped-and-recaptured Luke is marked for breaking and humiliation and forced to dig his own grave, then fill it in, then endure a beating by guards (one of many inflicted in the film). His sobbing and agonized groveling for forgiveness (“I got my mind right!”) is pure Christ-on-the-cross: a demigod pushed to the limits of even His endurance. It turns out that Luke’s collapse both is and isn’t a ruse. He confesses to Dragline that he didn’t spend his subsequent stint as a water-and-gun-fetching handmaiden merely biding his time until he could steal a truck and make one last break for freedom (“I never planned anything in my life”). By Luke’s admission, The Man really did break him—for a while, anyway. But that renegade spirit must’ve been in the back of his mind somewhere, because he’s Luke.

Luke has his official “Why hast thou forsaken me?” moment in an abandoned farmhouse near the end of the film, right before his crucifixion by gunshot. He even peers up into the rafters as if expecting God to answer him back. God doesn’t—but the film had already established, in a long, painful scene between Luke and his chain-smoking mama, that The Father ducked out a long time ago. (Perhaps not coincidentally, Time Magazine had posed the cover question “Is God Dead?” two years earlier, in 1965.) Religion, leadership, hero worship and celebrity blend in the character of Luke and through the performance of Paul Newman when the hero is returned, bleeding and close to death, after an escape attempt, then chastises his bunkmates to “Get out there yourself! Stop feeding off me!” Bob Dylan and John Lennon probably dug that. Probably a lot of superstars still do.

“Cool Hand Luke” is very much of its period, but what a fascinating period it was! Counterculture attitudes were bubbling up into mainstream entertainment all over in the mid-sixties. Nineteen sixty-seven, the year of this film’s release, was a watershed, marking the appearance of “The Graduate,” “Bonnie and Clyde” and “In the Heat of the Night.” Just five years earlier, novelist Ken Kesey had scored a major critical and popular success with “One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest,” another blatantly allegorical prison drama about, basically, a badass Christ figure who stuck it to The Man (though in Kesey’s case, the prison was a mental hospital and The Man was a woman named Nurse Ratched). Another 1962 novel, Anthony Burgess’s “A Clockwork Orange,” was a more formally daring and hard-to-stomach take on similar subject matter. Stanley Kubrick’s film version might make for a fascinating double feature with “Luke,” particularly for scenes where antisocial types are abused, humiliated and (in theory, anyway) broken, not so much for any specific crimes but because they pose a threat to authoritarian control.

“Luke” is one of those movies that seemed almost irredeemably dated maybe thirty years after it came out, but then left period associations behind and became timeless. It has its absurd or regrettable touches—such as that moment where the sexy young farm wife washes a car, nearly fellating a hose and squashing her breasts up against a passenger side window; images quickly appropriated by TV ads and sketch comedy shows—but its vagueness has proved more a benefit than a liability. The filmmakers, including cinematographer Conrad Hall, really did know what they were trying to do, and how to do it. Newman, his costars and the land itself earn the overused adjective “iconic.” At times they are posed like figures in a 17th century oil painting, a church ceiling mural or a stained glass windowpane. It’s easy to imagine people from any culture watching this film and seeing themselves in it. It is a masochistic fantasy but also a story of survival, and the need for heroes, even flawed, reluctant or inscrutable ones.

“He was smiling,” Dragline tells his bunkmates after being returned to the camp after Luke’s death. “That’s right. You know, that, that Luke smile of his. He had it on his face right to the very end. Hell, if they didn’t know it before, they could tell right then that they weren’t gonna beat him. That old Luke smile! Old Luke, he was some boy! Cool Hand Luke. Hell, he’s a natural-born world-shaker.”