A titanic pledge consumed Czech writer/director Václav Marhoul for over 11 years. Although others had fruitlessly sought permission to adapt Jerzy Kosiński’s 1965 novel The Painted Bird into a feature film, he was granted the opportunity to finally materialize it. Revered as a literary masterwork, the text centers on a Jewish boy left to fend for himself and traverse Eastern Europe during World War II. Each stop along his journey brings about a new encounter with despicable cruelty and sorrow—an aspect of the story that remains just as affecting in Marhoul’s screen version.

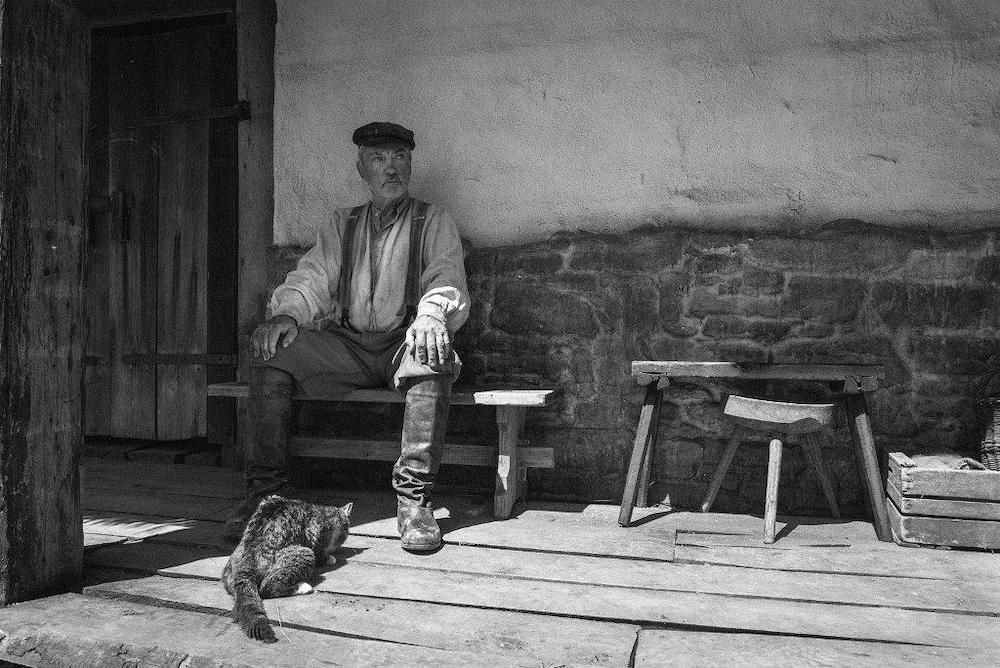

Executed with striking black-and-white cinematography, this retelling of “The Painted Bird” features a devastating performance by non-actor Petr Kotlár as the young protagonist, as well as a stellar global cast that includes Harvey Keitel, Stellan Skarsgård, Udo Kier, Julian Sands, and Barry Pepper. Marhoul, who was a producer for several years before jumping on the director’s chair, elicited evocative imagery out of Kosiński’s pages without downplaying the harshness of the reality he described: a world where being different makes you a target for evil.

Unwarranted controversy, believes Marhoul, has followed the movie since its premiere at last year’s Venice Film Festival due to the implied violence that plagues the narrative. But despite how grueling some have found it, the artistic merits of the filmmaker’s third effort have also been just as highly praised and landed it on the nine-film shortlist for the Best International Feature Film Academy Award representing the Czech Republic. A cinematic achievement of utmost humanity, Marhoul’s “The Painted Bird” is one of the most rewarding and astoundingly poetic viewing experiences of the year.

All three of your feature films to date have been adaptations from novels or plays. What was your entry point into “The Painted Bird”? Were you able to infuse a personal touch into a pre-existing work of such fame?

While I was researching what had been said about “The Painted Bird,” I found that many people thought it couldn’t be turned into a film because it was too brutal and complicated of a story. Jean-Claude Carrière once said—and I think he is absolutely right—that the problem of any adaption from any book into a movie is that each person will have his or her own key into the material. He said that maybe the key is for you to read the book, open the window to throw the book out in the street, and then sit and write what you remember. That’s your key, what you remember is your key, is what you consider important. Other things might not be important for you but could be important for another screenwriter.

If you are adapting a book or anything into a movie, you are not only adapting the book, but also your life, your experiences, through that book. My own life is channeled into the screenplay. When I was 15 years old, I started attending the film secondary school here in the Czech Republic, but it was a boarding school and all students lived together. There, older students bullied all of us younger students very brutally. It wasn’t about them telling me, ‘Give me your money’ but about physical violence. That was the first time in my life that I really encountered evil in people. I learned what people could do to each other. There are those who bully another person who is younger or who is weaker, and they are really pleased to do it. They enjoy being evil. Let’s say that my access into that character, a small Jewish boy, was a personal one because I can say very openly that I did understand it much better because of the years I spent at the boarding school.

Since you were able to relate on an intimate and human level with the boy’s circumstances, was it more challenging to fully comprehend the macro elements of the war unfolding around him and how these affect the individual?

There are also two other experiences that influenced me. The first is that I’m still serving in the Czech army as a professional reservist, and in the past few years I’ve been on missions in Kosovo, Iraq, and Afghanistan. I saw so many people suffering. The world of war is a different world. War is the most terrifying thing in the world. My grandfather fought in WWII against the Nazis, and I’m convinced that if you are confronted with evil you have to do something. It’s not that I like uniforms or armies, but I do believe that somebody must do something. In those missions I witnessed terrible things, like the Taliban killing 12 children because they were playing volleyball. I couldn’t just stay home while that was happening, and hope somebody else will solve it. Fortunately, I was never in a position where I was forced to take anyone’s life.

The last thing is that for many years I’ve been working for UNICEF and last year I spent 10 days in the refugees camps in Rwanda to organize nutrition programs for all the refugees—supplies and water—from several African countries. These are people who escape their countries because they are running away from criminal gangs. All of these experiences from the past few years, my life and my sensitivity, were implemented in the writing.

Had others tried to adapt the book into film and failed? Are you aware of any of those attempts?

Many people had tried to get rights and to shoot “The Painted Bird” before me. For instance, one of my actors, Julian Sands told me that Warren Beatty, who I love from “Bonnie and Clyde” and “Reds,” had tried. Beatty is such a famous director and actor and he was a really close friend of Jerzy Kosiński, so he asked Kosiński to get the rights to make a movie, but Kosiński never approved it. I’m the first guy in the world that got the rights from the Spertus Institute for Jewish Learning and Leadership in Chicago.

Once you had the green light to make “The Painted Bird” into a film were you concerned about how to tackle the brutality within the book’s pages?

For me it wasn’t about the violence and the brutality, for me it was about the three most important things in our lives: love, good, and hope. When I would say this people looked at me and said, “You must be crazy. It’s not about those things,” and I said, “Yes it is because this story is based on their absence.” The COVID-19 pandemic is an example, because we only realize how important it is to be healthy when we get sick, before then you don’t think about it. We only think about how important it is to live in peace when we are living in war. “The Painted Bird” is about the absence of love, good, and hope, because we only realize how important these things are when we are missing them. That was the key for me. The violence and the brutality in the story are only a frame but not the picture. What’s important is the picture inside, not the frame. Violence and brutality are only the logical consequence of a conflict. The presence of violence wasn’t important for me, but logical.

I feel the film is more about what the audience thinks is happening, rather than what’s actually shown on screen. But even so, some might find it unbearable to withstand. It definitely causes a reaction in people. Love it or hate it, one can’t be indifferent.

If you see the movie you know that in fact I never show the violence. I shot the violence with decency. The camera is always behind the violent action happening. For example, when the women are killing Ludmila on the meadow, you know what’s going on, but me, as a director, I would never show it. I never tried to make a shocking movie. My ambition was to make a truthful movie. Even if you can never shoot the absolute truth, any fiction should try to be truthful. If an art piece is truthful people feel an emotion. Any art piece, whether it’s music, literature, or film are about emotions. If you are listening to music and you are shaking, you are feeling an emotion. Then logically that’s good music. If you aren’t feeling anything, then that’s shit. My ambition was to make a truthful movie that brings questions but no answers. That’s how I felt about the book, which brought me so many questions and no answers. Questions like, “Why did God create human beings? What’s the reason? What’s the difference between really believing in God and only visiting a church to pretend I’m a god Christian?” Or, “Why does evil seem stronger in comparison to good?”

Those were some of the questions I asked myself reading it. One of my intentions was for the audience to follow me on my path through this film so that they can find their answers by themselves. I’m not proposing any answers. I didn’t want to be sentimental, or romantic. I understand that for some people my movie is very hard to watch, but it’s not because they actually see violence on screen, but because they are feeling what’s going on and that’s more powerful. They are going to have to think about these questions, and sometimes it’s painful to think.

Do you think that’s why some people walked out of your film during some festival screenings? How much truth is to those accounts?

Oh my God, the walkouts. That started in Venice, where we had the World Premiere, because a Polish journalist started writing about alleged mass walkouts. I don’t know why they would write that, because on YouTube you can find a clip of the ten-minute standing ovation at the end of the screening in Venice, and the screening room was absolutely full. Maybe only about five or so people left. Some might say that I’m only saying that to save face, but the corpus delicti, the proof, is in that video. In any case, this fame has been following my film since then, and some of the stories are hysterical and crazy. The Sun in the U.K. wrote an article about “The Painted Bird” saying that somebody tried to escape from the cinema at a screening, and that I personally held the door so they couldn’t leave! The truth is that among all the films selected to the main competition in Venice, “The Painted Bird” was the only really controversial movie. Even though “Joker” is much more violent than “The Painted Bird,” that movie didn’t have this problem with the jury or the audience.

However, I must tell that my biggest success with this movie, beyond getting into the Oscars shortlist and Venice, was that in some cinemas where they sold popcorn to the audience about to watch my movie, when the screening finished, all those people who bought popcorn, they didn’t eat it. I hate popcorn at the movies, so it was wonderful to see that when the screening ended they just threw away the popcorn in the dustbin. They simply couldn’t sit and watch my movie while eating popcorn. This is one of my biggest achievements with this movie.

Why do you think people are okay with the type of violence portrayed in a film “Joker”?

The explanation is quite easy. “Joker” is simply a fiction. It’s a fairytale tale based on a comic book character, and even if it’s much more violent, people are able to enjoy it. The problem with “The Painted Bird” is that it’s truthful, and “Joker” is not truthful. Since the “The Painted Bird” is a truthful film, it brings much more emotional pain to audiences.

Since your approach and Kosiński’s are much more blunt about the depiction of events, do you find that American movies about the Holocaust, such as “Schindler’s List,” perhaps romanticize them to make them more palatable for audiences?

I’ve watched so many movies about the Holocaust. In my opinion, Spielberg’s “Schindler’s List” is a good movie. Even though it’s a very sentimental film, it’s not part of what I call the Holocaust industry. Some of my colleagues are shooting Holocaust stories because they think they will get noticed. They think they are going to get awards or Oscars. As someone with Jewish heritage, I call those films the Holocaust industry because they are only speculating about the Holocaust. They are not truthful. I feel like I can recognize a good movie and a bad movie, and for instance one of the best Holocaust movies I’ve ever seen is the Hungarian movie that won the Oscar, “Son of Saul.”

But for me “The Painted Bird” is not a Holocaust movie, it’s not about the Second World War. I refuse for it to simply be a movie about the Holocaust. Yes, it’s set in the Second World War and the main character is a Jewish boy, but for me “The Painted Bird” is about very big principles. It’s timeless. The main idea can work in a story about a Black man among white people, or any story where the issue is that you are different from the majority. That’s why “The Painted Bird” has a great symbolic scene when the bird catcher puts the bird back into the sky, and its flock kills him because he is different. It’s not only about the color of someone’s skin, but the problem we faced when we are different for whatever reason. That’s why I always say it’s not only a Holocaust movie, or a wartime drama, because if I were to shoot it as a science fiction about a child from Earth who is abandoned in Mars it would still work. What happened in Eastern Europe during the war happened everywhere, and it’s still going on. In this very second as we talk to each other, there are children around the world who are dying.

Often when people ask directors, ”Why did you make this movie?” and most of my colleagues say, “I make my films for the audience.” But I’m very frank and I say, “I’m making my films for myself.” Of course, I’m glad if the audience enjoys them and that’s wonderful. I always say that for filmmakers, and maybe for all artists, there are only two paths to take. The first one is the path of sex and the second path is love. Sex means that you are going to direct maybe 50 commercials a year, plus two TV series, and maybe one feature. That’s sex because you are doing all those things for money. Then there’s love, which means that you have only one lover, one project, you fall in love and you must do it. In all my films I’ve followed the path of love, I would never like to take the one of sex.

Young actor Petr Kotlár is truly a revelation in how he conveys a wide range of emotions in a nearly silent performance. Was he found through an arduous casting process or did you have someone in mind before you started the project?

It was by accident. I met him at a sports stadium. I write all my screenplays in a wonderful medieval town in the south of the Czech Republic. It’s a very mysterious town. All of my screenplays I wrote in the same hotel, in the same room, same table, same chair. Around the corner from the hotel there’s a park, and everyday when I finished working, I went to that park to drink a glass of wine. Petr’s grandparents run this park. One day his grandparents invited me to the sports stadium, and that’s where I met Petr. At that time he was only six-years-old, three years before principal photography began. I’m crazy, because I simply felt that he was the character. I didn’t do any casting. I didn’t try to find another boy who could have been “better,” I just felt it was him. He had never been in front of a camera, but I was certain. My heart told me it was him.

Since your lead actor was a young boy and the material contains some very harsh sequences, how aware was Petr of the situations his character faced and how did you ensure his psychological safety throughout the production?

In general, he knew what the story was about, but he wasn’t aware of the details of what was going on. I worked with him very carefully. For example, the scene I mentioned when those women are attacking Ludmila in the meadow. Because of the editing, people feel that the boy is present and that he is watching the scene, but in fact that morning I shot the five shots that only show him because with camera shooting from the left angle. Then I sent him away and we turned the camera around and shot the brutal scene. Later the editors put it together. I use that method many times throughout the production. There’s also the scene when he is sleeping the first night in Labina’s house, and she is masturbating behind his back. He is standing in front of the camera, and Labina is behind him. I told the wonderful actress Júlia Vidrnáková to only do the physical movement pretending she was masturbating but to be totally silent. And to Petr I said, “This is your first night in Labina’s home, she went to sleep, but she is snoring loudly.” His reaction you see on screen is him thinking that she was snoring very loudly.

Sometimes I would use his dog as a tool to connect him with his emotions. He is a boy who loves animals and he loves his dog very much. When I wanted to build up emotion on his face and mostly in his eyes, I would say, “You are walking your dog and then suddenly he disappears. Where’s your dog? Maybe some bad guy stole him.” He is a very sensitive child and his face would reflect those emotions that I needed, even if he wasn’t outright crying.

Still, sometimes, I had to tell him the truth. For instance, I did mention that the bird catcher was going to commit suicide and that his character would jump on him to add weight and help him go faster. I have four children and children are not stupid, they understand so many things. At the time Petr was already 10 years old. I explained to him, “This sometimes happens in our lives. Some people fall in love, and when they lose that person they don’t feel like they have a reason to continue and they choose to leave this world.” He understood. I always told him it was only a movie and not the real world; “We are just pretending.” Before shooting he was tested by one of the best Czech children psychologists to ensure his emotional safety. He is simply a happy child, but he doesn’t want a career in acting. This was it for him.

Has Petr seen the completed movie? Even if he is probably too young to do so, he must be curious right?

His parents finally decided he could watch it for the first time at the Prague premiere. I didn’t like this idea. Like with the screenings before, I thought he would only be there for the introduction and then after the film. But he is not my son, and his parents decided he could watch it. I eventually agreed because I knew that even if he watched the movie, he still wouldn’t really “see it” at this age. Many actors, when they see a movie they are in, they don’t watch the movie; they are watching themselves on screen. I thought Petr would make the same mistake, and that’s exactly what happened. He was bothering people sitting around him because he would point at the screen and say, “Look at me!” He was being loud and commenting about the scenes [Laughs]. He watched it, but he’s never “seen it.”

Over the course of the film we see both Petr, as his character, change both physically and emotionally. It’s a gradual evolution that resonates strongly as we go further into his journey.

Principal photography took one and a half years. We had 104 shootings over that time in 47 locations across Ukraine, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and Poland. I also shot it chronologically. If I had said to any producer, “I would like to shoot the story chronologically,” they would have said I was crazy and that we must save money. But thankfully I did have a wonderful producer: myself. Me as my own producer understood why I needed to do that. That’s why I was able to shoot it chronologically, because I produced it myself.

This decision was of course because of the changing seasons that we needed to show, but also because I really tried to follow Petr’s transformation. I didn’t want to use makeup to make him look older. It had to be truthful. I believed this was the only way to achieve that. It was obvious that Petr was going to change throughout the making of the movie, not only physically but also mentally. It was so important to follow him, to observe him, and to understand how he is growing up in front of out eyes. When we started to shoot he was nine-years-old, and by the time we finished the shooting he was 11. There was such a big difference between those two years. By the end he was much more mature, because the film gave him so many experiences. It was hard for him because he was around only adults for such a long time.

Tell me about working with cinematographer Vladimír Smutný again, who is best known for “Kolya,” and the decision to tell the story with a stark black-and-white palette.

“The Painted Bird” was our third film together. I can’t really imagine doing it with anyone else. He’s not one of the best cinematographers because he’s great at composing shots, lighting perfectly, etc, but because his camera always serves the story, he tries to find its essence, its self-contained speech. That’s why his camera is actually different in every movie. “The Painted Bird” was such a challenging project. We spent one and a half years on it together while we were filming. Every day we talked, invented, searched. We were like twins. We’ve become one body, one soul. I’m one of those filmmakers who—even despite today’s amazing possibilities of digital filmmaking—is convinced that the negative is basically irreplaceable. That it gives every film a kind of magic. The negative is more authentic, and particularly for something like “The Painted Bird,” which is in black and white precisely to reinforce the basic narrative line. Filming it in color would have damaged it. It would have looked entirely unconvincing because my ambition was to film not the truth, but a truthful story. It was about making the most of the story’s possible authenticity, which could only be done using black and white.

You have an enviable ensemble cast that features some of the most renowned international actors from around the world. How much of a tough task was it to get them all on board for a project of this nature?

It was quite hard at the beginning, because they are in-demand talent. They have so many screenplays sent to them, and the problem is that nobody has the time to read so many screenplays. But there were two things that worked in my favor. One was that all of those international actors I cast knew “The Painted Bird” as a book. All of them had read it, and even if they did when they were 18 or 19, they remembered it because it was so influential in their lives. The second factor that really saved me was that they were all really curious about how I had been able to write the screenplay, because so many people thought that this book simply couldn’t be filmed.

The first one I persuaded was Stellan Skarsgård. He was so important to have as part of the project. He told me, “Look Václav, the screenplay must be really good. If the screenplay is really good I promise that I will act in your movie.” Once he saw the screenplay, he was the first one that I secured. Of course, if you are talking to those actors, their agents ask you, “Who else?” Barry Pepper I cast after I had already shot with Harvey Keitel, Stellan Skarsgård, Udo Kier, and Julian Sands. When Barry Pepper’s agent asked me who else was part of it, I just said all the other names, and the gate opened immediately. It was a stamp of approval. They thought, “It must be a good movie if those people are involved.” When I chose those big actors I was thinking purely as a director. I didn’t cast them because they are famous. I just realized they were the best. Also, since “The Painted Bird” is a worldwide bestseller I thought I could ask anybody even if I’m a Czech director living in Prague. This was always an international movie.

Was your decision to use the Interslavic language motivated by the need to have this international cast speak a common tongue or were there other practical or thematic reasons for this choice?

There were two reasons why I chose the Interslavic language. The first was because Jerzy Kosiński himself never said where the story is happening in his book. He never mentioned Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, or any specific country. I thought about that, “What does this mean? Where is the story going on?” But the second reason was much more important for me, I realized I had to find an unofficial language, because I didn’t want any specific nation associated with the story. The things the people in the story do happened everywhere. If I had used Ukrainian, then it would have unfairly been about Ukrainian people. That’s not fair for any country. I got the idea when I opened Google and typed “Slavic Esperanto” and it does exist, it’s known as the Interslavic language. Only about 40 around language actually speak it. It’s a mixture of all Slavic languages, except Russian.

I really pushed Julian Sands, Udo Kier, and Harvey Keitel because their characters had to speak the Interslavic language. It was so difficult for them. I still had to dub all of them, because for an American actor like Keitel it was impossible to make the required sounds of Interslavic language. That meant that, since they were going to be dubbed, part of their performance was about getting the lip-syncing right. Even if they weren’t able to pronounce the words properly, the lip-syncing had to be accurate. If I hadn’t focused on the lip-syncing and had asked them to speak in English, people would have realized they weren’t speaking Interslavic language even after dubbing, because the position of the lips in the pronunciation is very different. They all struggled a lot with the Interslavic language. It was particularly difficult for Harvey Keitel because he has more lines than the others.

On the subject of language, throughout the story we don’t know the boy’s name, and in sense that impacts his humanity. What’s the significance of discovering his name?

A little boy, our main character in a way represents the plight of thousands upon thousands of nameless children who have met the same fate. That we learn his name only in the film’s final scene is—along with the final song—a symbolic expression of the hope that he will find his place again, his human nature (which he gradually, and not by his own admission, loses) so that he can perhaps return to the light from the darkness of his battered soul.