To kick off the 10th anniversary presentation at Chicago’s Music Box Theatre, “Noir City,” a week-long festival celebrating the history and glory of film noir running August 17-23, will be presenting an Opening Night tribute to one of the modern masters of the genre, director Carl Franklin. A former actor who kicked off his filmmaking career working in the trenches for Roger Corman, he had his first big breakthrough with “One False Move,” a harrowing and powerful 1992 neo-noir about a trio of homicidal criminals (Cynda Williams, Michael Beach and Billy Bob Thornton, who co-wrote the screenplay with Tom Epperson) on the run to a small Arkansas town following a series of drug-related murders and the local sheriff (Bill Paxton in one of his first lead roles) who is preparing for their arrival and who shares a long-hidden secret with the woman. Although the film would go on to be celebrated as one of the best of the year and announce Franklin as a filmmaker to watch, the production company behind it had consigned it to direct-to-video oblivion and it was only due to the enthusiasm of critics like Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel, who saw it and raved about it whenever they had the chance, that it was given what proved to be a successful theatrical release.

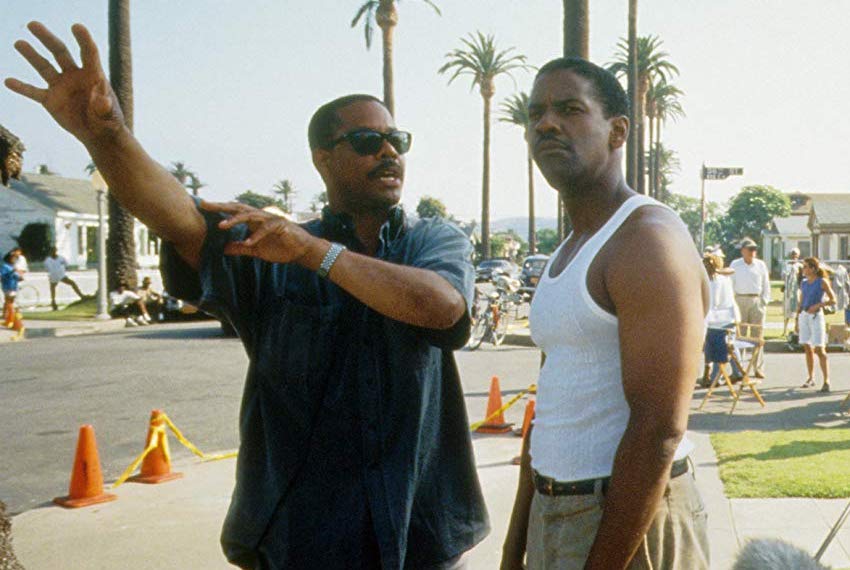

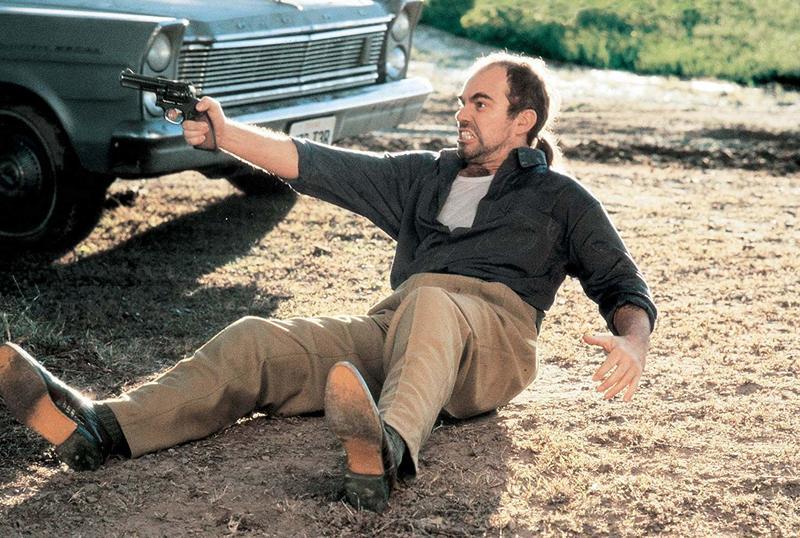

The success of “One False Move” brought Franklin to the attention of the studios and, with the assistance of Jonathan Demme, he was able to set up an adaptation of Walter Mosley’s 1990 novel “Devil in a Blue Dress” (pictured above), the first of a series of mysteries set in post-war L.A. and centered around the character of Easy Rawlins. A machinist unable to find work and struggling to make the payments on his cherished house, Easy (Denzel Washington) agrees to navigate the city’s predominantly African-American milieu in search of a missing white woman (Jennifer Beals) and quickly finds himself contending with crooked cops, sleazy politicians and an increasing number of dead bodies that he is about to be arrested for murdering. A near-perfect evocation of the noir form without ever becoming a slave to its elements, this proved to be an almost insanely entertaining film that told an engrossing story, looked fabulous and was further supercharged by performances by a pitch-perfect Washington and a then-relatively unknown Don Cheadle, whose turn as Easy’s loyal-but-homicidal pal Mouse was one of the great star-making turns of the decade. Alas, when it came out in 1995, it did not fare well at the box-office, meaning that one of the few attempts to establish a film franchise where one might actually want to see future installments never got off the ground beyond the first, albeit masterful, effort.

Franklin, whose subsequent career has included such further noir-influenced projects as “Out of Time” (2003) and episodes of such television shows as “The Riches,” “House of Cards” and the upcoming miniseries “I Am the Night,” will be appearing at the Noir City festival on the evening of August 17 for screenings of “One False Move” and “Devil in a Blue Dress”—both presented in 35MM—and will be doing Q&A’s after each one. Recently, Franklin got on the phone to discuss his fascination with film noir and the appropriately twisted journeys that “One False Move” and “Devil in a Blue Dress”—both of which are as good today as they were when they first came out—took to make it to theaters.

Many of the projects that you have worked on throughout your career have contained elements of film noir—“One False Move” and “Devil in a Blue Dress,” of course, but also things like “Out of Time” and some of the television shows that you have done episodes for, as well. When did you first become interested in the genre and what is it about it that holds such an appeal to you?

Even before I really understood film noir—and I am not saying that I do now—when I was a kid, there would be those old movies on television like “The Big Sleep” or “Lady in the Lake” and Robert Mitchum, who should have been the quintessential Phillip Marlowe, in “Farewell, My Lovely.” Of course, “Chinatown” was an incredible film—I don’t know how many times I’ve seen that one. It is a genre that I have sparked to but interestingly enough, “One False Move” was not my creation. They came to me with that. I did some work on it but basically, that script was Billy Bob Thornton and Tom Epperson. It was a great marriage for me in terms of what I like to do. “Devil in a Blue Dress” was something where my wife, Jesse Beaton, responded to the cover of the book in a bookstore and sparked to the story because at the time, she was having to sell her house and that paralleled Easy’s issue. Then I read it and I loved the world, especially the look at black Los Angeles at that time—it was noir that represented something I had never seen.

You had directed a couple of films for Roger Corman before doing “One False Move.” How did that screenplay end up coming your way?

Jesse had been in sales and acquisitions at Island Alive, who had marketed some pretty special films like “Baghdad Cafe,” “Mona Lisa,” “River’s Edge,” “The Trip to Bountiful” and “She’s Gotta Have It.” There was a guy named Larry Estes from Columbia/Tri-Star Home Video at the time, they were funding IRS Media. She met him at a party and he was very impressed with the work she had done and told her that if she get a good script and a director and a lead they approved of, they could make a low-budget film through the deal with IRS. She looked through a bunch of directors, and they had to be non-union since the budget was so small and they couldn’t afford to pay an established director. I had done some stuff for Roger Corman and what happened was that she contacted one of the producers over there and they suggested me. Other people had been suggested as well but it was really my short (“Punk”) that I had done at the American Film Institute that convinced her that I should do it. She hired me and IRS had actually tried to get me to do a film a year earlier, which was kind of a racial comedy with some. It was kind of edgy and the comedy was such that it really depended upon its offensiveness—I told them that I didn’t want to rewrite it because that would take the guts out of it but it just wasn’t something that I could do. They had already approved of me to do that film so they were fine with me doing “One False Move.”

When it came out, I remember that there was some degree of controversy about the level of violence in the film. However, once you get past the undeniably brutal opening scenes, there really isn’t that much violence to be had for most of the remaining running time. However, the threat of possible violence can be felt throughout and is hard to shake, even if you have seen it more than once and know what will or won’t happen. What was your approach toward staging the film’s violent content?

You watch movies because you want to see what other people are doing. I watched a lot of movie that had handled violence like that and you saw a lot of really violent acts but nobody was responding to them. I remember “Total Recall” in particular because you had people being held up as shields and et cetera but the only time anyone really responded was when a goldfish bowl broke and the goldfish were gasping for air. So I thought that I wanted people to respond to the deaths of people. That was important because, as you say, you start with the violence and it really sets the tone of who these people are who have committed these acts. The structure of the movie is not a traditional one where you have your protagonist go out into the world and comes up against the opposition and overcomes it by being active. In this case for our protagonist, the opposition comes to him so we needed to establish the threat that they represented so that we care and so that there was dramatic expectation throughout. The violence was necessary but I didn’t want to do graphic stuff.I wanted it to be like local news violence where you actually did have a sort of emotional commitment and emotional response to what you see, as opposed to just having people get exhilarated from the violence, like with gunfights with a lot of lead flying and a lot of activity.

Watching “One False Move” today is now a different experience than it was when it came out in 1992 because it now plays as a testament to the talents of the late Bill Paxton. Before doing this film, he had attracted a lot of notice in supporting roles in films like “Aliens” and “Near Dark” but this was one of the first opportunities he had to play a leading role. What was it that led you to casting him in the lead and what memories do you have of working with him?

He was a guy that, for whatever reason, we immediately thought of but Bill’s profile wasn’t strong enough at that time for the production company to hire him. We actually had to go out and see a lot of other actors first, who all turned us down. Thank God, because we wanted Bill. Bill was one of those people—and you can kind of tell it from watching him—where what you see is what you get. He’s a very upfront guy—I don’t know if Bill is capable of lying. He was a guy who was guileless—a clear channel. The thing about him is that because he had done roles like “Aliens” where the character was a little broader and he was playing it almost as comic relief, he wasn’t sure about himself as a leading man. I wouldn’t say that it was a challenge but it was something new for him, that he was actually a guy who could play the straight man in this. He was fantastic and I cannot see anybody else in the part. I always felt that it would be something that would take him into that next area and that he was a leading man. Bill was one of those guys who was always excited about what he did and honest and hardworking.

One of the most incredible facts about “One False Move” is that it even though it had a successful theatrical run, it almost bypassed theatrical release entirely to go directly to video and was only saved from that fate thanks to the help of critics like Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel. Looking back, what are your thoughts on that part of the film’s history?

Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel gave me a career. I get a little choked up. What happened was that IRS Media was primarily a straight-to-video company and weren’t really equipped to market films theatrically. They didn’t really have a lot of faith in “One False Move.” What happened is that my wife, Jessie Beaton, who produced the film, got it booked and Anne Thompson saw it at the Palm Springs Film Festival and John Hartl saw it in Seattle. Then Sheila Benson saw it and took it to the Floating Film Festival. That is where Roger Ebert saw it and he and Gene Siskel just became champions for it and talked about it on whatever show. They single-handedly became our marketing. My wife convinced the production company that it would get strong reviews in three places—Seattle, Los Angeles and Chicago—and if it was given a release in those three cities, those reviews would come out and they would be able to quote them on the boxes and sell more units. Then, because of people like Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert, it just caught fire and played in 51 markets. I don’t know how to thank them enough. Chicago is very important to me because of that.

“Devil in a Blue Dress” was both your theatrical followup to “One False Move” and your first work for a major studio. How did that all come together for you?

I was interested in the book and “One False Move” had come out and gotten great reviews and become a kind of classic little cult film. Now the studios were interested in maybe giving me a chance to direct a studio film. One of those studios was Sony/Tri-Star and it just so happened that Denzel was there. Jonathan Demme was interested in the Easy Rawlins books, Denzel wanted to play the character, Sony was interested in me being there and I was interested in doing it. Jonathan asked me what I wanted to do since he had a deal there and I said that I wanted to do “Devil in a Blue Dress.” It all coalesced and all the forces came together to allow us to make the movie.

In addition to directing, you also wrote the screenplay as well. What were the particular challenges in adapting Moseley’s book into a film?

The challenge that is always there in turning a book into a film is that in a book, you can have an internal conflict within a character while in a film, the conflicts have to be between the characters so that there is something to see and so that you can have the visual component. What is interesting is that Walter Moseley had written a few drafts of it—I think it had been at Universal—and they had sent him down a very difficult road because they wanted to combine the characters of Easy and Mouse so that Easy would become more of a traditional Hollywood take-charge kind of character. So Mouse was not even in the draft that I read. Jesse and I were in Minneapolis shooting “Laurel Avenue,” which was a HBO miniseries, and she saw that Walter was going to be at a book signing. We raced over there that night and she had her books for him to sign and I was there. When we got to the head of the line, I asked him why he had taken Mouse out of the screenplay and he said “How did you read my script?” I told him I had seen it and he was very happy to let me write it because they had put him through so many obstacles and hurdles during its development at Universal. In the meantime, a woman named Donna Gigliotti helped us get it out of there and we got it over to Sony, where they allowed me to do the script.

With “Devil in a Blue Dress” being a more classical example of the film noir genre, were there any films in particular that you looked at as part of your preparations?

“The Big Sleep” was the movie in terms of the look that I wanted. Tak Fujimoto was the cinematographer and I told him that I wanted it to look like black and white in color, to have that feel. One of the things that we did was we desaturated everything. We had no real primary colors, just a lot of earth tones with the girl in the blue dress being the only really vivid color. We beat everything down in the wardrobe and we tried to select what we shot. That was one of the things that Coppola did on “The Godfather”—instead of using a lot of filters, they actually made sure that they shot orange and black. That was one of the things that we decided to do—to shoot certain colors—so that it would have a certain immediacy while at the same time help make the period look seem convincing. I decided to approach it more as social realism because I figured that the noir would take care of itself because the elements were there. It wasn’t really like we tried to have the lights and moonlight streaming through the blinds and cigarette smoke and the kinds of things you normally associate with the stereotypical visual elements of noir. We kind of felt that if we used pools of light and kept things dark and contrasty and muted, the world that we saw would take care of itself.

One of the things that makes the film work so well is the casting. Denzel Washington was the perfect Easy Rawlins—even today, I cannot think of anyone who could even come close to being a better fit for the part. As for Don Cheadle, this was, I think, his first significant film role—he was doing “Picket Fences” on television at the time as I recall—and turned in one of the great out-of-nowhere scene-stealing performances of recent memory. How did he come about in the casting process?

I had worked with Don before—he was in the film that I shot as my thesis film at the AFI—so I was familiar with him. The concern I had about Don was that he was younger than Denzel and they are supposed to be contemporaries. We had to age Don a little bit and Denzel just does not look his age at all—he looked like he was around 30 years old and Don was about that age. He came in to audition and just blew us away. When he worked with Denzel, it was just the perfect fit, the two of them. Once I was convinced that they could be contemporaries, it was an easy choice.

In preparation for this interview, I put on “Devil in a Blue Dress” for the first time in a long while to serve as a refresher. When it came out in 1995, I remember liking it a lot but watching it again, I was completely knocked out by how great it really was. Therefore, it strikes me as being even more baffling that this film did not go on to inspire an Easy Rawlins film franchise.

Interestingly enough, that genre—as much as we may like it—has not ever really been a particularly commercial genre with the American public. “Chinatown,” as fantastic as that movie was, and it is a perfect film in my opinion, was not a huge success financially at the time. Even “L.A. Confidential” really only became financially successful after it got all the awards. It is just not a big moneymaker. We like noir and I think people who love cinema like noir but the average moviegoers who are into the big action films, especially at the time when we were coming out, it did not reach them until it hit DVD and cable television. Nowadays, people know the film but at the time, it was not a big box-office hit. With the studio paradigm that everything has to hit big in its first or second weekend, they just did not feel they could make the kind of money they needed off of it. The idea was to do a series based on the books. At the time, we optioned all three of the then-existing books—Devil, Red Death, and White Butterfly—but we didn’t get a chance to make the sequels.