We are republishing this piece on the homepage in allegiance with a critical American movement that upholds Black voices. For a growing resource list with information on where you can donate, connect with activists, learn more about the protests, and find anti-racism reading, click here. #BlackLivesMatter.

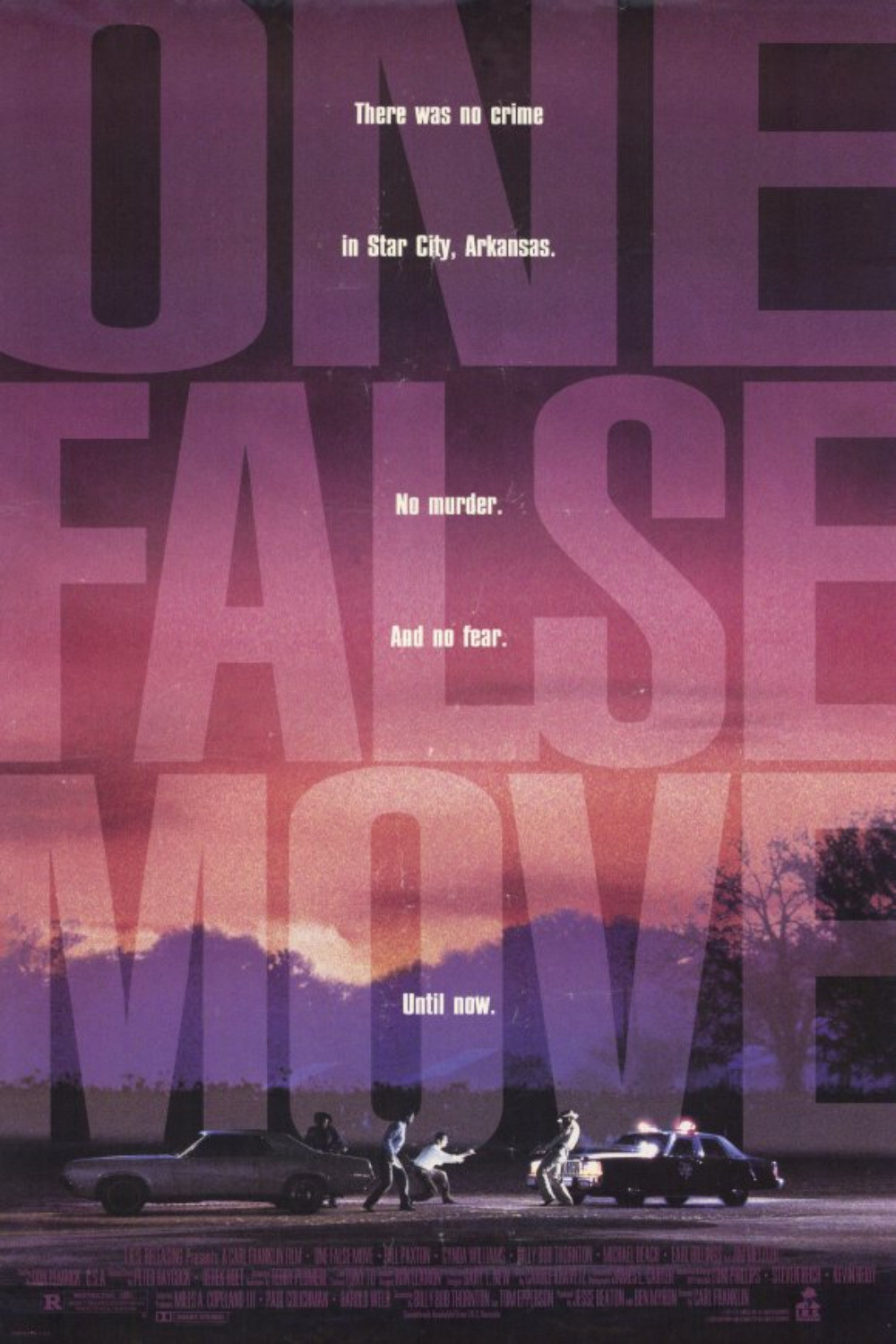

Here is a crime movie that lifts you up and carries you along in an ominously rising tide of tension, building to an emotional payoff of amazing power. On the very short list of great movies about violent criminals, “One False Move” deserves a place of honor, beside such different kinds of films as “In Cold Blood,” “Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer,” “Badlands,” “The Executioner’s Song” and “At Close Range.” It is a great film – one of the best of the year – and announces the arrival of a gifted director, Carl Franklin.

Yet no words of praise can quite reflect the seductive strength of “One False Move,” which begins as a crime story and ends as a human story in which everything that happens depends on the personalities of the characters. It’s so rare to find a film in which the events are driven by people, not by chases or special effects.

And rarer still to find a story that subtly, insidiously gets us involved much more deeply than at first we realize, until at the end we’re torn by what happens – by what has to happen.

The movie was written by Billy Bob Thornton and Tom Epperson, who begin by telling one story – about three criminals on the run from Los Angeles to Arkansas – and end by telling two. The second story involves the interaction between a small-town Arkansas sheriff and two tough Los Angeles cops who fly out to join him in a trap for the fugitives. The movie pays full attention to the dynamics of both groups, the cops and the killers, and then quietly reveals a hidden connection between them – a secret that I will not reveal, because it generates such a moral and emotional force at the end of the film.

“One False Move” begins in Los Angeles with a series of brutal murders of people in the drug underworld. Three people are involved: two men who have teamed up to steal drugs and money, and the girlfriend of one of them. They’re played by Billy Bob Thornton as a violent, insecure red-neck type; Cynda Williams as his lover, a black woman obviously deeply wounded in the past, and Michael Beach as the partner, a black man whose wire-rim glasses and impassive reserve conceal a capacity for sudden, cold violence.

Their original plan is to sell the drugs in Houston, but after they’re identified as the fleeing murderers they change course, heading for the small Arkansas town where Williams’ Fantasia was born and raised. The movie cuts ahead to the town, where we meet a cheerfully ambitious young sheriff, nicknamed “Hurricane” and played by Bill Paxton as the kind of guy who knows everybody in town and has never had to draw a gun in six years. He is mightily impressed when two Los Angeles detectives (Jim Metzler and Earl Billings) fly out to join him. He thinks he might be able to make the big time in L.A. himself some day.

The screenplay intercuts between these two storylines in a way that makes it increasingly important to us what will happen when the fugitives arrive in town. This isn’t the usual formula of the cops and criminals drawing nearer, but a more subtle approach, in which secrets about the past are gradually revealed that raise the stakes.

One of the strengths of the film is the way it draws its interpersonal relationships. As the Thornton and Williams characters veer unhappily between protestations of love and outbursts of accusations, Beach sits quietly to one side – on a motel bed, in the back seat of the car – talking in a low, controlled voice. Most of what he says makes sense, and is disregarded. Meanwhile, in Arkansas, the two visiting cops, one black, one white, joke about the aspirations of the local lawman, whom they see as a naive greenhorn.

But his knowledge about the town goes very deep, and what he knows about the fugitives provides the key to the movie’s last 30 minutes.

Carl Franklin’s career has been mostly in acting until now, on stage and in several TV series. He directed some low-budget exploitation films, attended the American Film Institute and then got “One False Move” as his first substantial film project. It is a powerful directing job. He starts with an extraordinary screenplay and then finds the right tones and moods for every scene, realizing it’s not the plot we care about, it’s the people.

One of the unique qualities of the screenplay, and his direction, is that this is a film where the principals are three black people and three white people, and yet the movie is not about black-white “relationships” in the dreary way of so many other recent movies, which are motivated either by idealistic bonhomie or the cliches of ethnic stereotypes. Every character in this film, black and white, operates according to his or her own agenda. That’s why we care so very much about what happens to them.