There’s no avoiding the contradictions in “Bombshell.” They’re baked into the film’s DNA. It’s story about a pervasive culture of abuse affecting countless women whose lives were irrevocably changed by the acts of powerful men, centering on women who would, by and large, reject the term “feminist”; a portrait of three women working within an organization actively ridiculing stories like theirs. That tension is a feature, not a bug. “I hoped that people on the right, especially,” director Jay Roach tells RogerEbert.com, “might pay attention to this film because of Megyn Kelly. That somehow, because it’s someone they knew as a star of that network, might watch her take on this issue.”

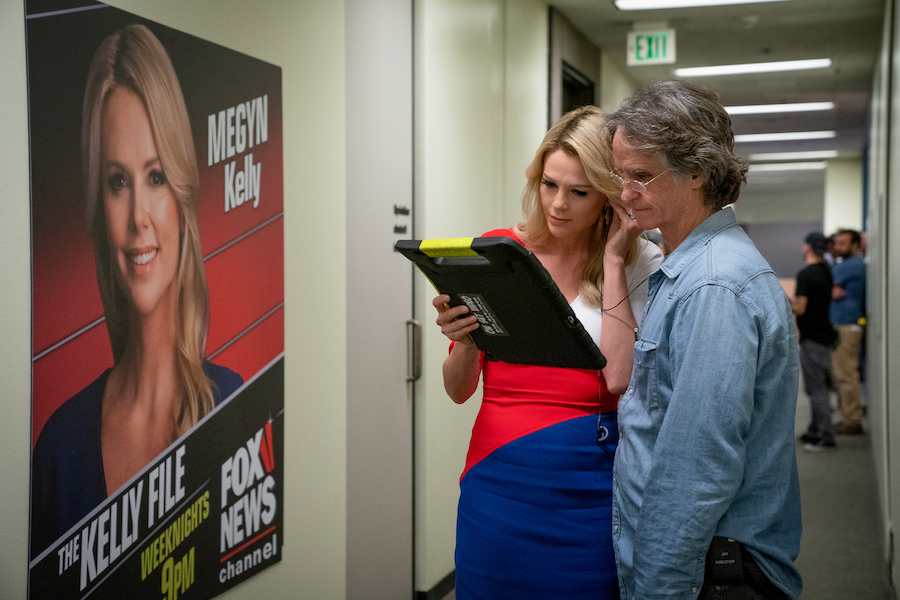

That’s a big hope for a movie, but Jay Roach isn’t new to such hopes. In recent years he’s made a habit of tackling big political stories and exploring the soft, human underbelly and the toxic result alike. Think of Julianne Moore’s Sarah Palin melting down in a situation she’s not equipped or prepared to handle, then giddily embracing her newfound celebrity and power in “Game Change.” Such moments can be found in “Recount” and “All the Way,” but “Bombshell” is a film full of them. It’s also a film anchored by tremendous performances: Charlize Theron’s Megyn Kelly, an uncanny impression that’s also a vivid, nuanced exploration of a contradictory woman; Nicole Kidman’s Gretchen Carlson, a portrait of tightly-capped, patient fury; Margot Robbie’s Kayla, a character created by screenwriter Charles Randolph to stand in for the women without fame to shield them from blowback, played by Robbie buoyant charm and immense vulnerability.

RogerEbert.com spoke with Roach about helping Theron, Kidman, and Robbie shape those performances, all the contradictions contained within the film, and the reasons Kate McKinnon should appear in more dramas.

“Bombshell” isn’t your first exploration of real people. What attracts you to those stories and, more specifically, to the stories of polarizing figures?

That’s a good question. I don’t usually think about it as being attracted to polarizing figures, but they are all often very polarizing. It’s hard to kind of make a blanket statement about them, but I’m just worried about how things are going. I’m always worried. I’m a worrier, so maybe this won’t help, to get into these stories, but I feel like because I care about how it goes, I’m always curious. Like, “How did that happen? How did they let this occur this way, and who was brave enough or strong enough or thoughtful enough to stand up against some of these people who it feels like we’re sort of victims of in a certain way?” We’re all sort of being constantly victimized by these ego-driven, power-abusing, power-obsessed people, but it’s always so interesting to see who dares take them on.

I hadn’t really thought about it, that that is something that’s in common in all of those situations. I grew up watching films like “To Kill a Mockingbird” and “All the President's Men,” or even “One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest,” where you would walk out of the theater saying, “Yeah, God damn it. Somebody’s got to fight for this.” When I come upon any story like that, it’s like, “Yeah, somebody should tell this story. Oh, I guess maybe I’ll spend my next two years telling it.” That’s how I felt when I read this script. What Gretchen Carlson did is incredible. I didn’t know she [spoke out against Roger Ailes] a year before the Me Too thing really kicked off with the Harvey Weinstein news. It had obviously been around thanks to [civil rights activist and Me Too founder] Tarana Burke, but it hadn’t exploded yet. So for them to think they could take on this incredibly powerful dude at this time was remarkable.

I don’t know. It’s therapeutic. I need some inspiration from somebody, and these characters that take on these abusive, powerful people … It’s not just men, obviously. I thought Sarah Palin was a powerful person too, who also was very ego-driven, but it’s most often men. That’s just the way it works.

Where in your mind is the line, when you’re working with actors, between doing an impression and creating a character? Charlize Theron is doing is both a great impression and giving a great performance; the same is true of Julianne Moore in “Game Change” among others. How do you go about helping an actor find that balance?

This is something we talk about a lot going in, and it’s different for different people. The all-encompassing answer is that I very much trust the actor’s instinct about how far to go, but I obviously have an opinion. In some cases, as with Charlize and a little bit with Julianne, they were so driven to get as close to a match as they could, mostly because it helped them get out of themselves. Charlize said to me, “I’m going to get this accent down, I’m going to have her body language completely down, and when I look at myself in the mirror, I don’t want to see my face while I’m doing it.” It helped her to get really close physically. Sometimes I also try to be the voice saying, “I really appreciate what you’re up to, but I also want you to let yourself come through a little bit because that’s where the audience is going to get in, because they have access to some aspect of your soul, your heart.” Once in awhile I’ll say, “Just do one that’s looser. Just let it go a little bit.”

But Charlize especially, she just had a great instinct for how far to go with that, and it’s quite close [to Megyn Kelly]. We’ve had people, smart, sophisticated people, wonder if we were doing archival footage at the beginning. She was that close. But I think she succeeds in having it feel more like she’s channeling the experience than that she’s doing a caricature or a mimicry. It won’t work if it’s only a match. But I think the audience really enjoys the high-wire act of the match—it’s more difficult, you can tell the actor’s having to sustain this other identity while also delivering on the performance. I try to give the actors whatever they need to get there, and I trust their instincts about it.

You’ve got this set full of people playing famous figures, many of them political figures. Then there’s Kate McKinnon, someone who’s well-known for doing just that on “Saturday Night Live,” and she’s playing a composite character. What was that like?

She and Margot are both composite characters. They’re both representing women that we didn’t have access to talk to directly, and we couldn’t name them even if we did. We had access to their stories, and we talked to women who [had similar experiences], but because they weren’t publicly out, if you will, we had to use these composite characters. We knew they would always be in scenes together. I wanted Kate McKinnon because the world of Fox has a certain amount of absurdity. There’s just a dark sense of humor that a lot of people have when they talk about their experiences there. I knew Kate could capture that. I knew she would find irony and, when she’s giving the tour [and talking about] what makes a Fox story, that she could take something that especially people on the left would be angry about when you talk about what Fox is up to … find an ironic distance, a kind of sense of the absurdity of it. You need funny people to do that.

I did not know Margot Robbie was going to be so capable of keeping up with her, even in the improv moments. [Most of] the script is not improvised, but a few of those moments with Kate and Margot are. The moments in bed, some of those moments where she’s telling stories about how she couldn’t get work anywhere so she took the job at Fox, but once she was at Fox she couldn’t get work either because she worked at Fox. A lot of that stuff was stuff they were just riffing on. I very often cast what I call comedy-capable people to be in dramas. You just don’t want, ever, it to be so heavy that there’s not … People cope with hard things with comedy, with sometimes dark, gallows humor and sarcasm. I needed people in every role, almost, who got that. Even John Lithgow, who’s playing one of the most dangerous and power-obsessed villains ever—he, as he in real life, was charming and funny. People described Roger Ailes as being one of the funniest guys you could hang out with at a party, even if you didn’t like anything about him. So I wanted to make sure we always cast people who could get that tone. To be more authentic, really, not just to be entertaining, although it’s more entertaining that way. It’s actually more authentic.

The most dangerous people are often “likable.”

Sometimes. Yeah, they’re dangerous because you let them in, let them close.

One of the most distressing scenes in the film is—

Margot.

Yeah. [The scene in question is Kayla’s first encounter with Roger Ailes; without revealing exactly what happens, it’s an upsetting and extremely vulnerable scene.] Given that there are also some very deep-rooted problems in the entertainment industry, how did you go about building that scene with those actors and making sure that it was a safe, healthy thing to play?

One of the most important things I did on this film, and I try to do it in all my films, is to acknowledge that I don’t know enough. I wouldn’t even be able to puppeteer people into some previsualized performance. I trusted Margot especially to [shape the scene]. We had done a ton of research, I had interviewed a lot of people who were at Fox and went through some of these things, and I conveyed to her what I had heard and what I had been told, but admitted that, “I’m a man, I could never possibly really imagine what this is like, so help me find it through your sense [of these things] as a woman, what you’ve been through, stories you’ve told, and I’ll put you with one of the great actors of all time as your nemesis. Playing Roger Ailes is John Lithgow, and he’s going to come at you. We won’t do all that many takes, we’ll shoot opposing angles. There won’t be coverage. We’ll shoot one direction, then shoot another direction, then go close. We’ll do the whole thing live and,” I even anticipated, “we probably won’t edit it down. I want it to be slow and excruciating, but you’re going to find it.” And she did. When you come up and find her face, after she’s been fully humiliated, I’ve never seen anything quite like that reveal.

I just tried to make it so that all of the forces at play were as deadly dangerous as they could possibly be, really for both characters. He’s the powerful person but he’s about to do one of the most soulless, heartless things ever, to put her in that position. In a weird way, both of their souls are at stake, so to somehow convey that to the actors —”This is a major thing. It happened with him many times with other women, but in relationship with you two together, nothing’s ever going to be the same for whenever you see each other again. She’s pushed to cross over a line, which you knew she would never cross, and then here she is crossing it.” By doing that, he gets his hooks in her. “You can now never talk about this. I know that, and I’m going to use that against you.” Again, it’s a great script, great writing, and just the most incredible actors, who take it to that other level of just utter dehumanization and abuse of power. So it’s just trusting actors.

You’ve said that sexual harassment is a nonpartisan issue.

It should be, right?

In your mind, and when talking with the actors, how did you reconcile the cognitive dissonance of what Fox News as an institution has done, what some of the women in the film have done—Megyn Kelly still says things like describing gender pay gap as a “meme,” she’s called the idea of affirmative consent “anti-men”—How do you sort of reconcile all that in your head? On the one hand, it’s obviously a horrendous wrong and a terrible abuse of power, and what she did is incredibly courageous. On the other hand, she’s also perpetuating the system she’s fighting against.

It’s something we’ve talked about a lot. I don’t agree with so much of what she says about those issues. She has a tendency, sometimes, just because something seems politically … that people are being attacked out of political correctness, therefore it’s her job to become the champion of the opposite. I guess I hoped that people on the right, especially, might pay attention to this film because of Megyn Kelly. That somehow, because it’s someone they knew as a star of that network, might watch her take on this issue. Even though she so vehemently denies being a feminist and doesn’t like that word, she did something that was inherently feminist. That’s complicated. There’s a conflict going on within her that clearly makes her right away a more interesting character.

Same with Gretchen. Gretchen has actually done a huge amount against forced arbitration, forced NDAs. Gretchen’s on a really interesting campaign to try to change all this. But I thought people, like in my conservative family, might pay attention because it was those women [and think], “Oh. I’m a little thrown off balance by this. My presuppositions are scrambled now because it’s those women taking on this issue.”

For people on the left, I hoped that it would become a feature of the story that women that they would’ve judged based on specific opinions they had, that they were somehow not capable of taking an issue on like this, or not deserving of respect for having stood up to a powerful man whose pattern of abuse is so similar to patterns of abuse in all walks of life. Certainly all news networks, evidently, or a lot of news networks, and a lot of entertainment business, but also in hotels, schools, fast food places, wherever. That somehow people on the left would say, “Well, just by having my prejudices challenged by what went on, does that mean I have to rethink Megyn Kelly or Gretchen Carlson?” That’s provocative at least. I don’t know, somehow it just seemed by just having it be that complicated, it might force it to become a topic of conversation. That it might challenge expectations on both sides. Whenever I see a film that shakes up my prejudices, I appreciate that, and I hope the film might do the same thing.

[This answer contains plot details from the end of “Bombshell.”]

There’s a sense of past, present and future with the three central women in the film. We’re encountering Gretchen after she’s decided to take action, Megyn as she’s in the process of deciding, and Kayla, who makes her decision in the final moment. It’s difficult to avoid thinking about in terms of the different waves of feminism. We’re told repeatedly in the film, and Megyn Kelly has said repeatedly in life, that she’s not a feminist, but it’s hard to kind of avoid that point. How do those stories sit in conversation with each other?

I think Gretchen identifies as a feminist now, probably, because she’s actually done a huge amount of work lobbying against forced arbitration and NDAs. I’m really proud of the way our film ends, because they tell her, “You’re going to get the apology, get the money, but you’re going to have to be muzzled,” and she says, “Maybe.” We did not know how much that was going to tap into what’s going on right now. But I have to credit Charles Randolph for the dynamic between all three of them. It was in the script, it was really well laid out in the script.

It was also a power thing, because Megyn Kelly, she’s a rising rock star and is going to end up getting access to as many attorneys as she wants and a big settlement. Gretchen is a somewhat-waning star at the company and has lost a lot of power. When she gets fired and sues, then she has zero power, and is actually at risk of losing all power that she’s ever had. In fact, she doesn’t ever get to work in broadcast news again. That’s the price she paid for it. Margot’s character, Kayla, is a powerless person entirely. She wants to get on the air and she wants to achieve some level of power. So I think Charles’ instinct was to have three women at [different levels of power] makes you realize that it’s risky for everybody, but it’s much riskier for someone like Margot’s character to take this on, and very risky for Gretchen too.

There is obviously a generational thing that he was trying to get to, especially with Margot’s character. She is meant to represent a new wave of people who might be willing to just say, “You know what, I’m not putting up with this anymore.” and she might walk out at the end of the story. It’s obviously having all three women and trying to go as a three-hander. Obviously, Megyn’s stands out because we start with her, but the attempt was always to try to make you care as much about each woman’s predicament but to compare them. It’s meant to say something about the differences between their different predicaments.