I have long admired Ethan Hawke but I was suddenly aware of the fact that he wasn’t in a lot of comedies, and that he as an actor didn’t have a long history of making me laugh. My colleague Will Tizard for Variety had asked him at this roundtable about the preparation he undertook before playing John Brown for the mini-series “The Good Lord Bird” and he mentioned going to his grave, picking up his straight razor, holding his gun, seeing where he lived. I found it interesting but my mind wandered to a scene in that series where his ward and audience surrogate Onion (Joshua Caleb Johnson) has finally had enough of Hawke-as-Brown’s lunacy and will be getting off the merry-go-ground. Onion later drifts into the church where Brown is speaking and Hawke plays him as comically depressed, barely able to get the syllables out, and there’s this cartoon elasticity to the performance that makes his sadness so charming and his inevitable bounce back so gratifying. Even when they gun him down you get the feeling he’s still out there, like some righteous avenging version of Sylvester The Cat. It’s a beautiful performance and it happened 35 years into his career. It’s like he’s just getting started.

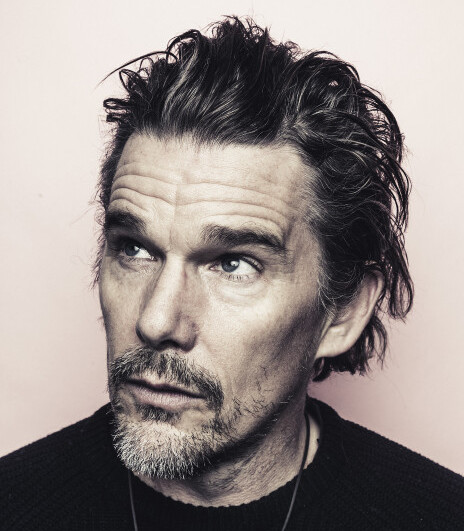

Karlovy Vary is giving him a lifetime achievement award at age 50, which he appreciates as a chance to look backwards appreciably and get excited for what’s next. He’d been interviewed by Neil Young before an audience an hour before they let a small group of us into a hotel room to get some slightly more intimate face time. Neil had brought up the laundry list of legends with whom Hawke co-starred early in his career and he’s still in a reflective mood, thinking about his “Dad” co-star Jack Lemmon, when he sits down.

“It’s crazy when I was a kid, Jack Lemmon was so famous and now young people they don’t know him at all.” Hawke went on a small tear during the talk about how bummed he was that young people don’t do their homework the way he wants them to. He’s met kids who profess to love film, his art, and yet willingly let blindspots stand. It winds him up. I can sympathize. “They still know Paul Newman and Steve McQueen but they don’t know who Jack Lemmon is at all. When he was alive he was very famous. Multiple Oscars … Those movies haven’t aged as well as other movies. My favorite is ‘Days of Wine and Roses, which does hold up. What’s the one with Marilyn Monroe?” He asks. “Some Like It Hot,” I remind him. “That’s it. Though they remember Marilyn Monroe, they don’t remember the two bumbling idiots.”

I seize on Tony Curtis because to me Hawke going from a sort of beautiful every-teen (a genuine teen idol, posters on every fourth bedroom wall) to a character actor without losing his Texan-by-way-of-New York dialect, the way words escape from behind his teeth like a heavy steam (a product of braces coming off prematurely so that he could star in “Explorers,” his first film role), reminded me a bit of Curtis. Curtis was an incredible performer, but you always knew it was him under there, even under all that ludicrous make-up in “The List of Adrian Messenger.” Lately however, Hawke has started to remind me of Sterling Hayden, especially his John Brown performance. Ever the know-it-all I take the opportunity to recommend the documentary they made about Hayden from the ’80s, “Pharos of Chaos.”

“Sterling Hayden, I like that. These are interesting comparisons. You ever read his book? The Wanderer? He’s an interesting guy. He was a troubled guy, more troubled than I am. I don’t know how other perceive you and your career is that interesting. Because it’s always different than how it feels. One of the things I’ve worked really hard to do is not think about it. Because if you think about it too much you start living in some weird forgettable biography instead of being present and living your life. You start going, Oh I’m this kind of actor and this kind of actor shouldn’t do this kind of thing. I remember … I hope you won’t mind me saying that Philip Seymour Hoffman told me the hardest thing that ever happened to him besides failure was winning an Oscar. You start to think about yourself in the third person, you know you’re in a taxi going: I’m an Oscar winner, why am I in this shitty cab? I should be in a nicer cab than this. And you go What is this voice in my head? It’s the way the flames of our ego get fanned. It can destroy us.

I feel sometimes in the positive end, and I’ve never said this out loud so I’m trying to weigh how it’s going to sound coming out, but when I think about the young women in their college dorm rooms with the posters for ‘Before Sunrise’ or ‘Reality Bites’ or something, there is a positive part of that of trying to be worthy of that. I want this book to be good enough for those people, now adults, to read, and not be disappointed that they wasted their time being interested in what I have to say. It’s a positive challenge. There’s a certain community who are huge Richard Linklater fans and they love me from those movies, and those movies are super connected to me because I helped write them and Rick’s my friend and we dreamed them up together. I have pride in that! The positive manifestation of pride is not do anything that might diminish that work, but the downside of that is you stop taking risks. One of the things I really believe in is that when you stop playing the fool, you take yourself too seriously, you atrophy a little. I’ve seen the danger of this period of life, where you’re getting the lifetime achievement award, is that you can believe it. I’ve met a lot of famous people who … let’s say their high water moment was 1988? They’re still living in 1988. It’s like they live in formaldehyde in glass where’s it’s still 1992 or 2002 or whatever. I try to stay out of formaldehyde as much as possible. And one of the ways to do it is to make an ass of yourself. But at least you wanna make an ass of yourself, doing something interesting. You play John Brown for instance you can fall completely on your face but if you do, you were at least trying to play John Brown.”

It’s that attitude that’s turned Hawke from a reliable, handsome matinee idol into one of our most interesting actors. I tell him it was gratifying in the extreme to come of age in an era where he went from a star to a kind of a bulwark against Hollywood mediocrity. Directors like Linklater, Michael Almereyda, the Spierig Brothers, Noah Buschel, and lately The RZA have used him like a talisman. They know he’ll give it all to a project that might not have a fighting chance at the American box office. It’s what’s endeared me to him for so long. I ask if there’s a moment when he realized he could be this thing.

“That is the evolution that happens through any kind of success as an actor. When you study the career of Paul Newman, for example. What starts to be your job is how to use your success. DiCaprio can greenlight a hundred-million-dollar movie. But you start to have success and you realize, I can help this filmmaker get their movie made or I could not. What is my role in the community? One is, yes, I wanna thrive as an actor. I wanna take care of myself. I know the best way to do that is to facilitate opportunities for other artists. When you’re having a shared creative experience generally it’s better than when it’s just in service of yourself. That’s been the hardest part of my job is how to put myself in a position to succeed. How to help people who deserve help who aren’t getting it. If you don’t make anybody any money you don’t get to play. It’s a weird situation. You gotta pay to play. Even a filmmaker as successful as Richard Linklater struggles to get his films financed because they’re not commercial ideas, they’re revelatory ideas. They’re movies celebrated in an environment like this but they’re really hard to get financial backing for.”

Hawke talks for a moment about his proposed next project, a movie about the transcendentalists, Emerson, Thoreau, the Alcotts. Linklater is apparently peeved that Hawke flew to Karlovy Vary to collect a lifetime achievement award instead of staying in with him working on the script, he says with a glint in his eye.

“So finding a balance between supporting filmmakers and to make films that are still lucrative enough that you can do that. You also wanna be in a position where when a director likes your work, Robert Eggers or somebody, and they wanna work with you they can actually hire you. A lotta directors don’t get to hire who they really want because they need to finance their movies. ‘Well I think this actor’s ok and they’re really famous.’ You have that happen a lot. It becomes this huge balancing act. With the benefit of hindsight ‘Cool Hand Luke’ seems like an easy choice to make for Paul Newman but Stuart Rosenberg had never directed a movie. He could have easily said no, and everyone would have told him it was smart. When I did ‘Before Sunrise”’the perception of Rick at that moment was he’d tried to make a Hollywood film and it failed. Their conception of ‘Dazed and Confused’ was that it was a failure. That’s how stupid they are, but you’ve got to be smart enough to go anyone who thinks ‘Dazed and Confused’ is a failure is a knucklehead. You have to have the courage of your own belief. Also, I should say, there a lot of successful actors who don’t care about independent cinema, it’s not their thing, but for me those were the actors I loved. I remember as a kid watching Max Von Sydow and saying That’s the dream. Being in Ingmar Bergman’s theatre troupe. Like SHIT, that’s the gold standard. They don’t have all the ancillary negative elements of celebrity, they’re just making high art at a high pace and working with the most talented people. And that environment …” Hawke pauses and his beautiful eyes seem to find a point somewhere a hundred miles away, his voice turns to the chilled whisper he’s so perfected in his genre films. “… You know you’re lucky if it’s once a generation. It doesn’t … It’s not there for you.”

Hawke doesn’t put a lot of stock in awards, though he enjoys what they can remind him of. He keeps a space in his home his kids call the “hall of ego,” filled with awards and red carpet pictures and reminders of his many year friendship with Linklater because his confidence is so easily shaken. He remembers the failures more acutely than the success, so it’s nice to remember he had a good Tuesday once upon a time. He still remembers when Pauline Kael, his and his mother’s favorite reviewer as a young man, panned ‘Dead Poet’s Society.’ He says he was proud to get that negative review. His years in genre filmmaking, perhaps his most interesting period, have yielded many a negative review but he keeps going admirably unabated.

“The question you asked earlier about where to take your skills; I do like to go places where they want me. I like these genre films in a way because there’s something really unpretentious about them, They don’t pretend to be important. You can do really exciting work without anyone noticing.” I ask him about the shift from warm and handsome leading man to a more stark and chilling presence in the likes of “Daybreakers” and “Sinister” and “First Reformed.”

“It’s slow when that happens. That’s an interesting question … when I was younger I would have definitely called myself a first-person actor. Writers write first-person or third-person. Lotta my favorite actors are third-person actors. They’re playing a character and they’re almost shamanistic ally shape-changing themselves. Then there are … Newman’s a good example, a first-person actor. It always seems like it’s Paul Newman. But he’s always different. And he’s always leading you. Paul Newman’s a lawyer! Paul Newman’s going to prison! Paul Newman’s a cowboy! But it has integrity because he’s a classic leading man. He’s using his instrument. In a way the same could be said about Nicholson. In his best roles he’s always Jack. That’s what we want him to be. It’s not one thing, he’s different in ‘Cuckoo’s Nest’ than he is in ‘Chinatown’ but it’s still Jack. The mischievous soul we all kind of long to be. The person not afraid to say ‘F**k you.’

When I was first starting I really couldn’t understand a character if it wasn’t through the first-person lens. I was always trying to turn the character into a version of me. I was happy and proud to do that, it’s what I wanted to do. As time went by that got less interesting. So I started to feel more confident in playing in the third person zone. If you’re a first person actor, you don’t want to put yourself in horror films, because your imagination says I don’t want to be attacked by demons! I’d rather be the leader of the group in ‘Alive,’ I want to stand on a desk, I want to see myself in that way. But as you to divorce yourself from your own id and sit outside of it you start to see how much of who “you” are is extremely flexible. Much more flexible than you thought. It’s exciting! Playing Chet Baker, for example, changing your vocal range and your inflections and your body language. I’m kind of in a period of about 30 years transitioned from being a first person actor to a third person actor.

Jeremy Irons [his co-star in the movie “Waterland”] had a big impact on me. He had great advice about the way to expand your range. It’s not, in his estimation, to say ‘Next time I’m going to play a 500-pound man with a Russian accent.’ It’s to keep inching it out so you can do it with confidence. If you get too radical you don’t take the audience with you. When Harrison Ford, a great actor, one of my favorites, plays a Russian [in ‘K-19 The Widowmaker’] you think “Ooh, I wasn’t ready for you to do that,” you know? I’m not even sure it’s because it wasn’t well executed but I just couldn’t go with you. Meryl Streep meanwhile has taught the audience to expect anything. I’ve been kinda slowly pushing the boundaries and then it gets exciting to Not do it, as well.”

The interview is over, we’re about to leave but he stops me, and points at my lanyard, on which the site name RogerEbert.com is emblazoned. The name hasn’t meant a lot here in the Czech Republic. I’ve met dozens of people from here, from the rest of Europe, from New Zealand, who just don’t know who he is, which has startled me somewhat. I thought everyone knew. Today is my last day before I head back to America and Ethan Hawke stops me from leaving, despite his having limited time.

“You know, I wanted to tell you … the namesake you’re working under. This guy Roger Ebert was really special. He was … I wanna tell you one funny story. My first film [‘Chelsea Walls’] showed at a festival. I made it on DV for 100,000 dollars. I worked my ass off on it but it’s kind of a mess. I think it’s remarkable when you realize I made it with a toy camera for a hundred grand in a couple days. I’m proud of myself. But it has to be seen in the context of its moment. I have no regrets about it. Do I think you should spend your days watching it? Probably not. But he gave it a bad review and I went up to him. He’d been really nice to me, and I said ‘Why’d you say that … that’s not true, what you said about that.’ And he said ‘I saw it at two in the morning and I was really tired and that’s not fair. I’ll watch it again.’ And he watched it again, reviewed it again, and he said that in the review, ‘You know, the first time I saw the movie I did not think it was good, and it’s a problem with film festivals. I had seen too many films and I was super impatient. If it’s gonna look this shitty I wanted to be more engaging … but then I saw it on its own terms.’

I don’t think he was being nice! He gave me a lot of bad reviews after that, plenty of bad reviews. But not many people would do that and not many people would admit that they were tired and burnt out. I did some panels with him on digital vs film and one time he gave a toast to me at an event once that still haunts me. It’s not true anymore because it was right before ‘Training Day’ came out and he said, ‘To Ethan Hawke … the most famous actor in the world who’s never killed anybody. I used to think you couldn’t be famous without committing a murder.’ And I never really got successful until I killed someone.”

I laugh, I’ve laughed as much during this interview as I have during “The Good Lord Bird.” Hawke smiles, that warmth back again, that movie star smile, his face a little older, his charm intact. At 50, Ethan Hawke has seen it all, done it all. But you take one look at him and you just know he’s going to keep having fun.