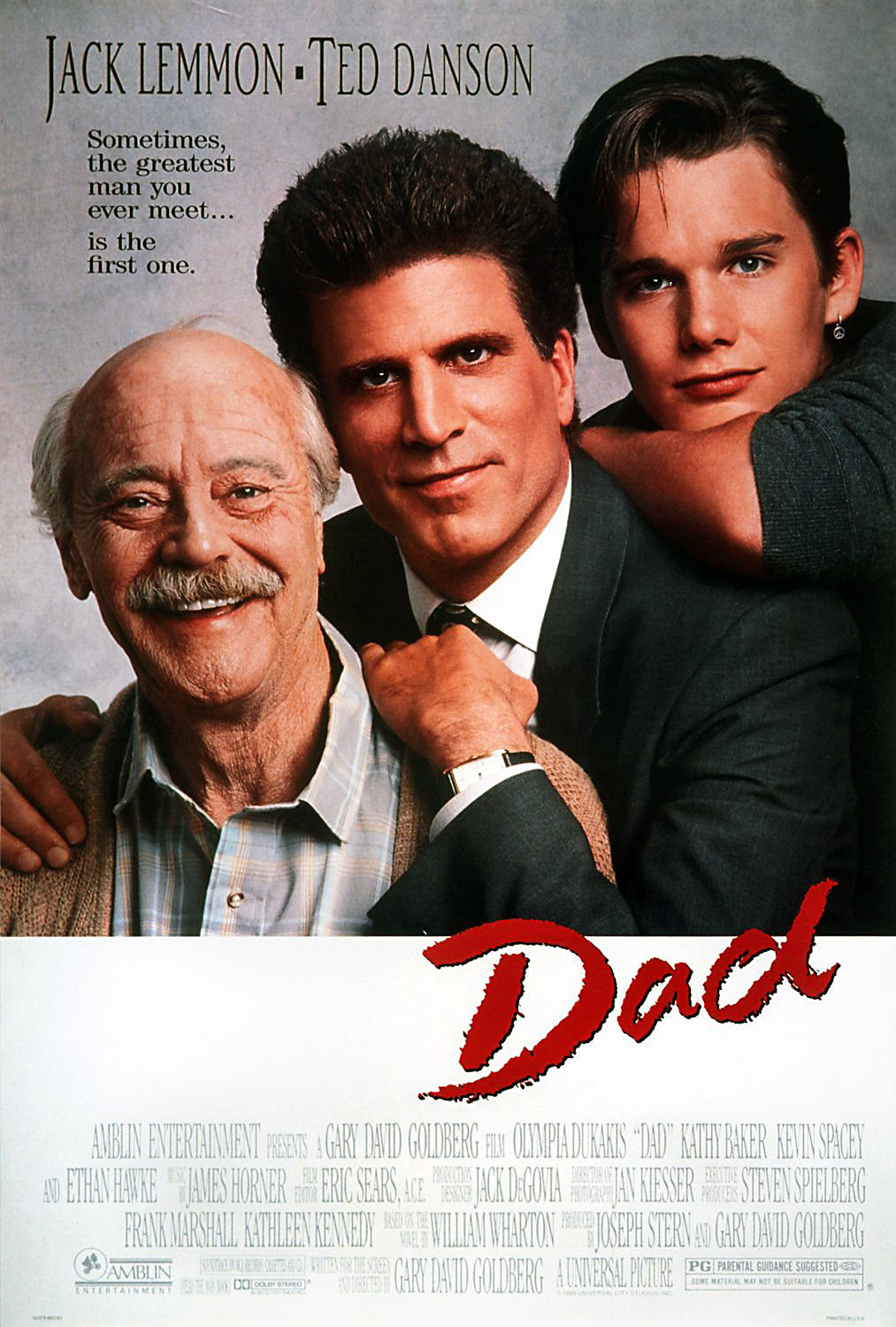

“Dad” is a case of a movie with too much enthusiasm for its own good. If the filmmakers had only been willing to dial down a little, they would have had the materials for an emotionally moving story, instead of one that generates incredulity. The proof of the movie’s promise is in the opening scenes, which work powerfully. The film doesn’t go bad all at once; it derails about halfway through The story involves an elderly married couple (Jack Lemmon and Olympia Dukakis) whose lives have settled into a rigid routine. She does everything – even squeezing the toothpaste onto his brush in the morning – and he has grown completely dependent on her. Then one day, during their ritualistic trip to the supermarket, she has a heart attack and is rushed to the hospital. Suddenly Dad is on his own.

The kids doubt if he can cope with daily life. There’s a sister (Kathy Baker) who still lives in the hometown, and a son (Ted Danson), a banker in the big city who has grown so remote from his family that he can’t even remember if he was home last Christmas, or the year before. Danson returns for a few days and tries to train his helpless Dad to do simple household tasks. He has a system of color-coded file cards, for example, with instructions like 1) “Fill sink with warm water” 2) “Squeeze in liquid soap.” The amazing thing is that Dad turns out to be more resilient than anyone would have guessed. As played by Lemmon, he seems at the beginning of the movie to be tottering on the edge of senility, allowing himself to be treated almost as a baby. But gradually he improves. And gradually the bond between father and son, which had almost been severed, re-establishes itself.

Danson returns to work briefly, taking his dad along to a board meeting at the bank. But then tragedy strikes: Dad turns out to have a virulent form of cancer. Danson goes on leave from his job and returns indefinitely to his small town, where he now finds himself acting as parent to his parents. This is a role many people are playing these days, and “Dad” might have had something useful to say about it, but it’s at just this point that the movie loses its wits and becomes unbelievable.

What are we to make, for example, of the scene where Danson grows angry with the hospital treatment Dad is receiving and literally picks up his father and carries him out of the hospital and takes him home? The filmmakers no doubt thought this would be an emotionally shattering scene, but they got carried away by their own zeal. No one who has seen an elderly parent through major surgery could believe the scene for a moment; such an experience would cause the patient excruciating pain and might kill him.

But Dad is a tough old bird – and, played by Lemmon, maybe too tough. With a sentence of death, he takes a new lease on existence and decides to taste joy and spontaneity for the first time in his life. To hell with what people think: He’s going to trust his feelings! It’s a good inspiration, but the movie takes it and goes berserk with it, turning into a silly sitcom just when we want to believe it the most.

I could believe, for example, the scene where Dad takes Mom (now mending from her heart attack) to visit the neighbors they’ve never met. This scene, played in a low key, is effective. But what about the absurd scene where Dad visits a used clothing store at the beach and comes back with what must have been a carload of purchases, since he stages a costume party in the living room? As Lemmon pops through the doorway in a series of quick cuts, wearing funny hats and silly shirts, I wanted to get out my scissors and go to work on the movie. The sequence is disastrous. And it ushers in a series of scenes that seem more inspired by sitcoms than by real life.

What went wrong? Why couldn’t the filmmakers tell their story simply and truthfully? “Dad” is based on a novel by William Wharton (who also wrote Birdy), and was written and directed by Gary David Goldberg. It’s his first feature, after years of directing TV’s “Family Ties.” Did he stop to reflect that movies allow their makers the freedom to be more thoughtful and observant, to take risks instead of treating the audience like simpletons? From the moment Danson carries his father out of the hospital, “Dad” abandons a realistic setup and flies off into fantasy. “Dad” plays a dirty trick on the audience by getting us to care more deeply about the characters than it has the courage itself to care.