Dubbed “Ambassadors of Compassion” by Chaz Ebert, nine Ebert Fellows graced the first panel of Ebertfest 2017, bringing a human face to the young generation tasked with spreading empathy at a time where there is very little in supply. A total of 24 Ebert Fellows are attending this year’s festival, many of whom were among the panel’s audience. Chaz called a few of them up to the mic, encouraging them to join in the conversation about how cinema can bridge gaps between different life experiences. Sara Pelaez spoke about a documentary she made about college sweethearts, and how she had to offer them her own vulnerability in order for them to open up on camera. Jason Yue contrasted the binary nature of science with the ambiguity of life, arguing that empathy is the bridge that can connect art and science. Robert Fowler pointed out that the more clearly defined one’s worldview happens to be, the more difficult it is for one to have empathy. Joshua Lee said that the internet has redefined the concept of community, providing people with a communal experience even while in physical solitude, though Kyle Burton mentioned how recent studies have shown that the empathetic nature of young people has decreased as their narcissism has risen exponentially.

The next panel featured several more of the festival’s cherished guests, each of whom discussed how empathy played a crucial role in their professions. Chicago Tribune critic Michael Phillips praised films that “transcend cheap sympathy and get into profound empathy,” citing how many romantic comedies “make it too easy for the audience” by clearly delineating the heroes and villains until they resemble caricatures. Only by complicating one’s sympathies can true empathy be achieved. Filmmaker Tanya Wexler related Phillips’ words to her own 2011 fact-based rom-com, “Hysteria,” in how her lead character, a doctor played by Hugh Dancy, evolves from a sympathetic figure into an empathetic one, as he regards the behavior of a strong-willed woman. In order to erase the disconnect between politics and popular culture (reflected by this year’s opening night film, “Hair”), Wexler stressed the importance of a “persistent shift in representation,” inspiring Phillips’ hashtag-worthy chant, “No transition without representation.” The fact that only one in four lines are delivered by a woman in films today is glaring evidence of the inequality that pervades modern cinema. Wexler recalled how her basic human rights—such as visiting her female spouse in the emergency room—were only very recently acquired, and that this social progress was largely due to programs like “Ellen” that Americans invited into their homes on a daily basis.

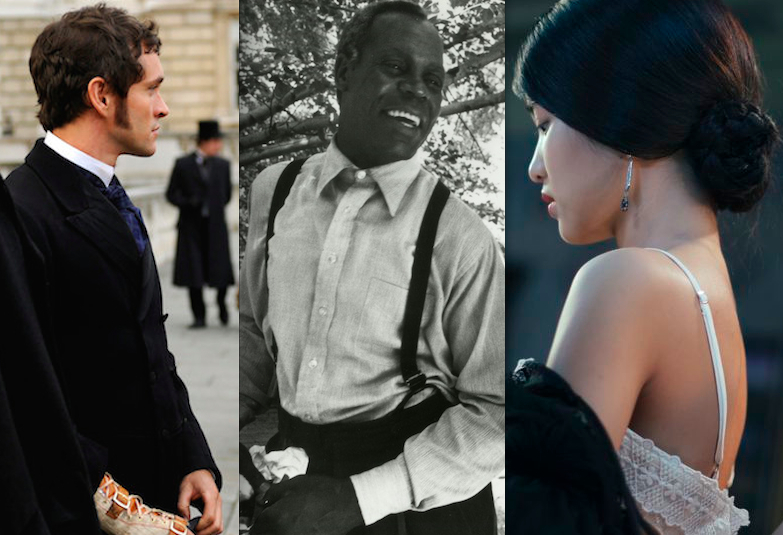

“Hysteria” was the second film to screen at Ebertfest 2017, and the response it received from festivalgoers was euphoric. Wexler delightfully portrays the absurdity of female sexual repression and demonization circa 1880 without downplaying the seriousness in her satire. Dancy’s character treats women diagnosed with “overactive uteruses” by developing the first-ever vibrator, which causes one patient to perform the funniest operatic orgasm since Madeline Kahn in “Young Frankenstein.” Chaz realized that the festival’s award—a casting of Roger’s upturned thumb—took on a rather hilarious appearance when presented to Wexler and Dancy after the screening of their film. RogerEbert.com editor Matt Zoller Seitz and critic Sheila O’Malley moderated the post-film discussion, earning nearly as many laughs as the film itself. Seitz observed how Dancy looked as if he were attempting to “fish a coin out of a couch” during his character’s initial scene of administering the “treatment.” Dancy revealed that he was given a sandbag, providing him “with something to lean into” during those scenes, which led him to develop blisters on his hands. Wexler recounted the tremendously arduous process it took for her to acquire footage of ducks copulating, a sight gag that sets up the film’s final crowd-pleasing punchline. All laughter aside, Wexler said that the “trust in women’s sound judgment” still remains questioned in our society, causing strong female voices to be dismissed as hysterical.

Independent film legend Robert Townsend (of “The Meteor Man” and “Hollywood Shuffle” fame) had a one-on-one Q&A with the revered auteur Charles Burnett (“Killer of Sheep”) after an afternoon screening of his eerily compelling 1990 drama, “To Sleep with Anger.” There are shades of Hitchcock’s “Shadow of a Doubt” in the film’s premise, though the picture could’ve easily borrowed one of the suspense maestro’s other titles: “The Trouble with Harry.” Danny Glover delivers what may be his career-best performance as Harry, a smiling, soft-spoken drifter who infiltrates the lives of a loving family with an insidious, possibly supernatural influence. There is suspense throughout the film, but it emerges organically out of the characters’ grounded, even tranquil world. Burnett said that all of Harry’s supposedly evil acts are all circumstantial, and that the character can’t even remember whether he had committed the crime in his past that appears to have doomed his future. In a moment of startling honesty, a member of the audience said that her identity as a white woman made it difficult for her to experience what the black characters were experiencing onscreen, even though she could recognize the situations that the film portrayed. Burnett said that her reaction is indicative of the fact that there aren’t nearly enough films “made by people of color,” echoing the words of Wexler during the morning panel. Despite the recent Best Picture victories for Steve McQueen’s “12 Years a Slave” and Barry Jenkins’ “Moonlight,” a black filmmaker still has yet to win the Best Director Oscar, an omission that is downright shameful. If there was any justice in the Academy, Burnett would have several Oscars on his mantle by now.

At the beginning of the morning panel, Chaz mentioned that a couple of this year’s films were sexually explicit, and pondered whether the educated audience populated by numerous Rhodes Scholars “would be able to handle them.” That question was answered with a resounding “yes” during that night’s screening of Park Chan-wook’s mesmerizing, erotically charged mystery, “The Handmaiden.” Critic Nell Minow was joined onstage by Seitz, Sam Fragoso (of the excellent Talk Easy podcast) and Ebert Fellow Katie Kilkenny (of Pacific Standard) for a stimulating post-film discussion that examined the picture’s enticing intricacies. Kilkenny astutely observed how the film’s elaborately designed house reflected its owner’s “monstrous obsession with colonialism,” fusing English and Japanese influences that are emblematic of the film itself. Based on an English novel, “Fingersmith,” by Sarah Waters, the film likens the subjugation of women by men to the Japanese occupation of Korea. Seitz said that the house reminded him of the dreams one has of a familiar space that continuously reveals newly discovered doors and passageways. It’s an exquisite example of a film’s visual landscape mirroring its narrative structure. As soon as the audience eases into the film’s character dynamics, they are constantly subverted and rearranged, while various scenes are revisited from contrasting angles. The journey may be daunting at first, but it pays off in moments of spectacular irony and humor. Fragoso mentioned that the best serious films also happen to be very funny, and this film is no exception.