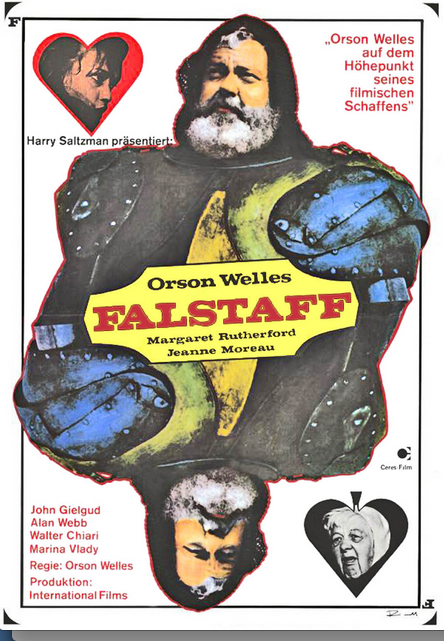

Great Movie / Roger Ebert / June 4, 2006

There live not three good men unhanged in England. And one of them is fat and grows old.

How can it be that there is an Orson Welles masterpiece that remains all but unseen? I refer not to incomplete or abandoned projects that have gathered legends, but to “Chimes at Midnight” (1965), his film about Falstaff, which has survived in acceptable prints and is ripe for restoration. I saw the film in early 1968, put it on my list of that year’s best films, saw it again on 16mm in a Welles class I taught, and then could not see it for 35 years.

It dropped so completely out of sight that there is no video version in America, Britain or France. Preparing to attend the epic production of both parts of Shakespeare’s “Henry IV” at the Chicago Shakespeare Theater, I wanted to see it again and found it available on DVD from Spain and Brazil. Both versions carry the original English-language soundtrack; the Brazilian disc is clear enough and a thing of beauty. What luck that Welles shot in black-and-white, so there was no color to fade.

This is a magnificent film, clearly among Welles’ greatest work, joining “Citizen Kane,” “The Magnificent Ambersons,” “Touch of Evil” and (I would argue) “The Trial.” It is also magnificent Shakespeare, focusing on Falstaff through the two “Henry IV” plays to his offstage death in “Henry V.” Although the plays are much abridged, it is said there is not a word in the film not written by Shakespeare.

Falstaff, “this huge hill of flesh,” is one of Shakespeare’s greatest characters — the equal, argues Harold Bloom, of Hamlet. He so dominates the Henry IV plays that although Shakespeare promised he would return in Henry V, he reconsidered; the fat knight would have sounded the wrong note in that heroic tale, and so we learn from Mistress Quickly of his death, as he “babbl’d of green fields.”

Welles was born to play Falstaff, not only because of the physical similarity but because of the rich voice, sonorous and amused, and the shared life experience. Both men lived long and too well, were at odds with the powers at court and were constantly in debt. Both knew disappointment, and one of the most sublime moments in Welles’ career is simply the expression on his face at the coronation of Henry V, when he cries out “God save thee, my sweet boy,” and the new king replies, “I know thee not, old man.”

Prince Hal, later Henry V, is played in the film by Keith Baxter, who looks dissolute enough in the roistering at the Boars Head Tavern, but as early as Act 1, Scene 2 is an unpleasant hypocrite in the monologue where he admits his present misdeeds but promises to reform at the right time. In Shakespeare, this is a soliloquy; in Welles, Falstaff listens in the back of the shot and is forewarned. Later, in an echo of that composition, the prince looks impatiently toward the field of battle as Falstaff, behind him, questions the concept of honor. That each man hears the other’s intended soliloquy adds a dimension to both.

Welles as director uses some of his familiar visual strategies; the vast interiors of Henry IV’s castles contrast with the low ceilings and cluttered rooms of bawdy houses, just as the vast space of Kane’s great hall contrasts with the low ceilings and dancing girls of the New York Inquirer. Royalty in “Chimes at Midnight” is framed by vast cathedral vaults, with high windows casting diagonals of light. Welles uses dramatic camera angles, craning to look up at the trumpeters atop the battlements as Henry IV rides off to battle.

At Mistress Quickly’s, on the other hand, Falstaff and his roisterers have great freedom of movement involving doorways and posts, barrels and vertiginous staircases, barking dogs and laughing wenches. He and other actors circle verticals and one another as they speak, just as Welles and Joseph Cotten circled in “Citizen Kane” and “The Third Man.” And watch the use of deep focus when he begins a shot with Hal seated in the background and, as news of his father’s death is conveyed, Hal stands and moves forward, finally looming over the camera in foreground. All one shot.

The scene of the battle of Shrewsbury is justly famous. It lasts fully 10 minutes, chaotic action at a brutal pitch, horses and men confused in smoke and fog, steel crashing against steel, cries of pain, desperate struggles, confused limbs caked in mud and blood, men falling exhausted or dead. Barbara Leaming, one of Welles’ biographers, says the scene was created by careful framing; Welles at no time had more than about 100 extras, yet seems to have a multitude, and the violence of the struggle was studied by Mel Gibson before he directed “Braveheart.”

The battle is intercut with shots of a fat man in armor, hurrying and scurrying out of the way and finally playing dead. When Hal finds Falstaff flat on his back, he cries out, “What, old acquaintance! Could not all this flesh keep in a little life?” We know Falstaff is not dead, and Welles finds a way to let Hal know, too: the frost on the old man’s breath puffs out from beneath his visor. Yes, it was cold. Welles shot on location in Spain, in winter; his first shot shows Falstaff as a tiny figure in a vast field of snow, his last shows Falstaff’s coffin being pushed across snow toward his grave, and in several of John Gielgud’s speeches as Henry IV, we can see the frost on his breath.

That Gielgud played the king and others such as Margaret Rutherford (Mistress Quickly) Jeanne Moreau (Doll Tearsheet) and Fernando Rey (Worcester) also appeared in the film is a tribute to Welles’ reputation, for on a budget of less than $1 million he was, like Falstaff, not prompt to pay. Gielgud plays Henry IV as a dying man almost from his earliest scenes, plagued with guilt because of how he won his throne. His son is no consolation; the king envies Northumberland his son Henry Percy, known as Hotspur (Norman Rodway), and wishes “would I have his Harry, and he mine.” He excoriates the thief and whoremonger Hal and his low companions, none lower in deportment or loftier in essential humanity than Falstaff.

How good is Falstaff? Consider the way warm affection illuminates the face of Jeanne Moreau as Doll Tearsheet caresses and tickles her beloved old rogue. Note the boundless affection Falstaff has for all around him, so real that even Quickly forgives his debts and allows him to contract new ones.

Such scenes illuminate the life Welles poured into “Chimes at Midnight.” He came early to Shakespeare; he edited and published editions of some of the plays while still at prep school. On stage and screen, he was also Othello and Macbeth, his voice fell naturally into iambic rumbles, he was large enough for heroes and so small he could disappear before Henry V’s scorn. He once asked an audience, reduced by a snowstorm: “Why are there so many of me and so few of you?”

There was not something Falstaffian about Welles, there was everything. As a young man he conquered all that came before him (at Shrewsbury a knight meekly surrenders to the old man, awed by his leftover reputation). Welles grew fat and in debt, took jobs unworthy of him, was trailed by sycophants and leeches, yet was loved by good women and honored by those who could see him clearly. And he battled on, Quixotic as well as Falstaffian, commencing grand schemes and sometimes actually finishing them (indeed, his “Don Quixote” can now be seen in intriguing but incomplete form).

The crucial point about “Chimes at Midnight” is that although it was rejected by audiences and many critics on its release, although some of the dialogue is out of sync and needs to be adjusted, although many of the actors become doubles whenever they turn their backs, although he dubbed many of the voices himself, although the film was assembled painstakingly from scenes shot when he found the cash — although all of these things are true, it is a finished film, it realizes his vision, it is the Falstaff he was born to direct and play, and it is a masterpiece. Now to restore it and give it back to the world.