Folklore, by its very nature, invites retelling, contextualizing ages-old tales for new contexts so their lessons can be imparted through more familiar lenses. Little Red Riding Hood, one of the most oft-retold, is no exception; its moral, that of the painful transition from innocence to adulthood, translates no matter when and where you tell it. Whether the 17th-century climes of Charles Perrault, with its wicker baskets and dangerous foot travel, or the cars-and-phones age of 2025, the elements remain elemental. A young girl lost in the woods. A helpful woodsman. Grandmother’s house. A big bad wolf.

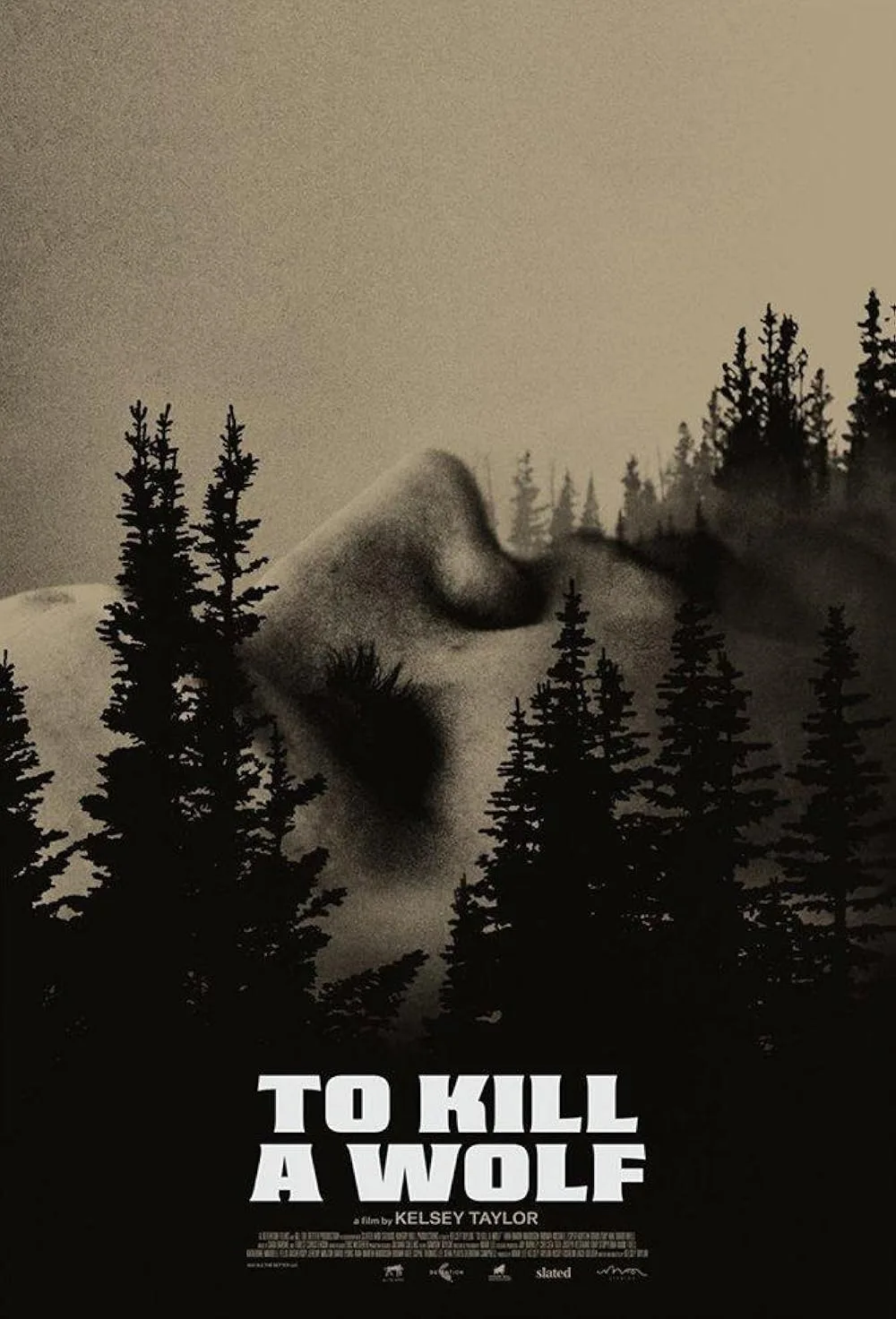

But where previous adaptations have leaned into the fantasy of wolves impersonating dead grandmothers, or even swung it into wilder genre directions (see Catherine Hardwicke’s “Red Riding Hood”), Kelsey Taylor’s feature debut “To Kill a Wolf” grounds the tale in the modern, real, and immediate. Here, it’s recalibrated as a muted interpersonal psychodrama—one where the big bad wolf may not have big teeth, but its appetites are just as dangerous to our young protagonist. And where the woodsman’s quest to save the girl also helps him heal wounds of his own.

The woodsman in question goes unnamed, played with wearied woundedness by Ivan Martin; when we meet him, he goes about his life of quiet solitude. He listens to records, goes out to check wolf traps, and bickers with the stuffed raccoon in his cabin (its name? Dave). But one day, he finds a 17-year-old girl named Dani (Maddison Brown), collapsed and catatonic in the woods. He brings her in, heals her up, and tends to her, even as she’s tight-lipped about what exactly she’s doing there. She’s clearly running from something, and won’t say what. However, the Woodsman, in his isolation, is experiencing his own kind of exile, and the pair must learn to confront their respective secrets in order to find catharsis.

Taylor, who worked previously on shorts like 2019’s “Alien: Specimen,” finds some interesting notes to play within the rhythms of the Red Riding Hood story. The tale is split into chapters—”The Woodsman,” “Grandma,” “Wolf,” and so on—reminding us of the elements from which this story is cobbled. It also lends these domestic dramas an air of the fantastical, elevating personal traumas to mighty beasts that must be slayed. Taylor’s script is sparse, but elegant, conveying volumes of emotional pain in wordless gestures, in little visual clues we see (the Woodsman wears a prosthetic leg, both testament to the loss he’s experienced and indicator that he might relate to the wolves whose legs get snared in his traps), in the little gestures that build its impeccable mood.

There’s an unshowy elegance to the craft on display; “To Kill a Wolf” plays out in a tight, boxed-in 1.55:1 (not quite widescreen, not quite Academy ratio), capturing the psychological confines both Dani and the Woodsman find themselves in. It also, fittingly, situates them within the tall trees of the Oregon forest in which this film was shot and set. Cinematographer Adam Lee’s work is superlative here, capturing the crisp moss, deep greens, and light snowfall on the Woodsman’s denim jacket with all the folkloric texture of “The Witch.” Shots peek in through trees, around leaves, up through lichen; it’s all brilliantly atmospheric in ways that emphasize the isolated nature of these characters without overplaying its hand. As the Brothers Grimm might put it: All the better to see it with, my child.

And then there are the performances, which Lee’s camera often captures in devastating close-ups to catch every naturalistic nuance. Martin’s stiff stature and stoic, Nick Offerman-ian melancholy hide deep wells of emotional pain, while Brown’s deep fragility shines through in flashbacks that finally show us the reason she might be fleeing on foot to, yes, Grandmother’s house. It’s here that another pair of strong supporting performances emerge, as we see the poisonous dynamic she has with her resentful aunt (Kaitlin Doubleday) and psychologist uncle (Michael Esper), the latter of whom imbues his nice-guy persona with its own sense of sinister predation. My, my, what big teeth he has, even as he hides them with an air of kindness and outward decency.

In stripping down the Red Riding Hood fable to more terrestrial environs, “To Kill a Wolf” finds stronger, more delicate ways to sell the simmering psychology of its original fable. Granted, some of the metaphor gets lost in the sauce, which can kill some of the romance of tales like these. But this is how I imagine a true Riding Hood story might play out: Two people running from deep emotional pain, stumbling around in their own awkward ways to help each other, and maybe coming out the other side of it a bit more healed. Its final minutes are as muted as the first, but in its small gestures towards brighter futures, it nails its simple truths without lapsing into melodrama. A tight, restrained, worthwhile first feature from a cast and crew whose next jaunt into the woods will surely worth sharpening our teeth for.