You probably couldn’t pay your average fanperson to sit through an Alain Resnais movie. And yet, one of Stan Lee’s first forays into motion-picture production, in the 1960s, was to collaborate with Resnais on a couple of screenplays. Smiling Stan is now known to millions of fanpersons as the avuncular comic-book creator behind characters such as Thor, Iron Man, and the rest of the Avengers. Not to mention Spider-Man. Lee, now 91, never misses a chance to cameo in the Marvel comics adaptations frequently unspooling at a theater near you. One element missing from the “Are There Too Many Comic Book Movies” debate flaring up in newspapers and at websites rather frequently nowadays is the fact that, once upon a time, the give-and-take between comics and movies happened on a pretty high intellectual level. Cartoonists such as Alex Raymond, Milton Caniff and others were frequently cited by the likes of Fellini and Resnais as seminal influences. There was no snobbery or affectation fueling these mutual admiration societies, just sheer creative joy at the possibilities inherent in cross-pollination. One of the discontents of the contemporary comic book movie is that, however much élan a creative head such as Joss Whedon or Jon Favreau can throw into a given movie, it all still feels very much controlled by the money guys. This has never not been the case, of course (many of the most superb collaborations in the comics medium fell apart because of shoddy contracts, and one reason Lee remains a public icon of comics creation has to do with his having become one of the money guys himself), but today it all just seems so obvious.

All this being the case, it’s worth taking stock of the cinematic great and near-great works that very happily and healthily derived from comic books conceptually, while not actually doing so literally. I’d say that these set a pretty high bar for those currently engaged in crafting “real” comic book movies.

(Artwork by John Lichman.)

“Dr. Strangelove Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb” (1964)

Stanley Kubrick and Terry Southern’s vision of nuclear apocalypse as frantic farce is both terrifying and hilarious. And its particular strain of comedy derives not just from the “sick humor” that writer Southern and his contemporary, comedian Lenny Bruce, specialized in, but also the inchoate-hip satire that was a staple of the comic-book turned magazine “Mad” and the fumetti-driven “Help.” (The latter featured work not just from “Mad” alum Harvey Kurtzman but also future Monty Python members Terry Gilliam and John Cleese).

The comic-book aspects of the movie include not just the outsize, caricature-like characters such as gung-ho bomber “King” Kong and paranoid General Ripper, but the character names themselves, all the way down to Dmitri Kissoff and “Bat” Guano. (The character that wound up named “Buck” Turgidson was named “Schmuck” in an early draft of the script.) Had the legendary pie fight in the War Room scene survived the final cut, it would of course have drawn a thread back to silent screen comedy. But it also might have looked like a giant-size panel in a Harvey Kurtzman/Will Elder collaboration.

“Alphaville” (1965)

Groundbreaking director Jean-Luc Godard shot his pulp sci-fi pastiche in contemporary Paris, not a special effect (unless you count toggling to film-negative imagery) to be seen. His protagonist was a secret agent named Lemmy Caution, an already-established character in “real” French B-pictures, played there as here by craggy American-born crooner turned movie tough guy Eddie Constantine. The love-conquers-technology storyline is countered by a distressed, pessimistic visual style. The action scenes are choppy, distinguished by jump cuts and stresses on specific acts of violence that evoke a topsy-turvy continuity in a series of geometrically uneven comic-book panels.

In a particularly poignant scene in the first third, Caution meets a mole stationed in the movie’s title city. Played by aged character actor Akim Tamiroff, he’s a sad old drunk and letch who informs Caution that the age of heroes is ended: “Dick Tracy est morte…Flash Gordon est morte.”

“In Like Flint” (1967)

This is the second of two films featuring the parodic super-duper secret agent Derek Flint, incarnated by a wickedly grinning James Coburn. The first, “Our Man Flint,” is an intermittently amusing close-but-no-cigar effort, partially due to its stolid direction by the relatively humorless Delbert Mann. The followup rates not only because of smoother direction from Gordon Douglas, but a cheeky (and by today’s standards, arguably infuriating) plot that has a proto-feminist group plotting world domination. Oh, and also the sets, which aped the innovative and wide-open crime caverns created by Ken Adam for the early Bond movies. Adam also designed sets for “Dr. Strangelove,” which is hardly a coincidence. In any event, the kookie comic-book aura of “Flint” was in consonance with the then popular, proto-campy “Batman” TV series.

At the same time, artist Jim Steranko was applying a Bond/Flint expansiveness to the layouts of his “Nick Fury: Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D.” comic book for Marvel, and leavening it with a psychedelic design sense. Days of miracle and wonder indeed.

“Le Samourai” (1967)

Here’s a first-rate example of the cross-germination between cinema and graphic storytelling. This story of an ultra-efficient hit man brought down by his hopeless love for an unattainable woman has been called a piece of “baroque minimalism” by Ginette Vincendeau in her biography of its director, the great Jean-Pierre Melville. Although shot in color, the movie’s ruthlessly muted palette gives it a mentholated noir feel, and its almost non-existent dialogue emphasizes the primacy of its visual storytelling.

Said storytelling not only draws from the tradition of Japanese scroll pictures—although set in Paris, the movie’s Asian influence is considerable—but from the lines and shadows of Milton Caniff, the pioneering cartoonist who created “Terry and the Pirates” and “Steve Canyon.” The stolid faces of the killers and victims, the precise lines of the brims of their fedoras—these and other elements could have been practically photocopied from a Caniff panel. But Melville’s own innovations with this first rate film would go on to influence another great pop-graphic artist. Frank Miller’s work on “Daredevil” and his practically silent graphic novels such as “Ronin” could not have existed without the example of Melville’s distillation.

“Star Wars” (1977)

George Lucas’ vision was not only informed by movie serials, Westerns, and Kurosawa pictures. Galactically wise white men in flowing robes had been a staple of the “Cosmic” comics produced by Marvel in the late 1960s. No Marvel maven can look at the movie subtitled “A New Hope” and not see just a little bit of The Watcher in Alec Guinness’ Obi Wan Kenobi. By the same token, Darth Vader is an ingenious amalgam of both Ming the Merciless (of Flash Gordon comic strip and then movie fame) and Marvel’s destroyer of worlds Galactus.

“Creepshow” (1982)

This homage to the ultra-icky EC horror comics of the 1950s—which were so over-the-top that they excited censorship pressures which led to the adoption of the bland-making Comics Code—is convincing enough that some folks think it really is a comic-book adaptation. But no—this George Romero-directed film anthologizes several stories dreamed up in the ultra-gory and grim EC tradition by Stephen King, a past master of such stuff.

The movie is especially adept at mixing goofily grim humor with its fright tales, as in the casting of Ted Danson and Leslie Nielsen as amorous rivals in the “Something To Tide You Over” segment. “Creepshow” can also deliver the gross-out goods with a very straight face when it likes: the final segment, featuring a stern E.G. Marshall as a neat freak one-percenter overrun by household pests is undiluted nightmare fuel for anyone with a bug aversion.

“The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across The 8th Dimension” (1984)

Earl Mac Rauch was a young—collegiate young—novelist whose debut attracted the attention of screenwriter W.D. Richter, who invited Rauch out to Hollywood. Richter was fascinated by the pulp/comic-book influenced tales Rauch spun around a rock star/ physicist/neurosurgeon whose charisma perhaps exceeds his monumental intellect. His posse of suave nerds is a superhero team without superpowers that winds up battling a mad scientist who’s also largely lizard. You don’t get more comic bookish than this, conceptually.

The low-budget production of this cult item is rightly legendary in the more esoteric circles of fandom, and the threadbare sets and effects arguably ameliorate the more sensationalist aspects of the story, which so impressed Rauch patron Richter that he made “Banzai” the first movie under his own production shingle, and directed it as well. In later years Rauch, who had also penned the script for Scorsese’s “New York, New York,” scripted several standalone “Banzai” comic books.

“The Terminator” (1984)

In his early years as an auteur, James Cameron didn’t mind wearing his influences on his sleeve. And in fact, his directorial breakthrough, a scrappy, imaginative and eventually legendary sci-fi thriller that was also something of a screen epiphany for title-role star Arnold Schwarzenegger, was the target of a plagiarism action brought by sci-fi author Harlan Ellison, who eventually won some dough and a mention in the movie’s revised credits.

Golden Age TV sci-fi wasn’t Cameron’s only inspiration. With his blacker-than-black shades, implacable jaw line, and barrel chest, Schwarzenegger’s T-800 is a Jack Kirby villain par excellence. And Michael Beihn’s earnest Kyle also looks as if he could have stepped out of any issue of “Fantastic Four” or “Thor” produced between 1966 and 1969.

“Aliens” (1986)

James Cameron’s sequel to Ridley Scott’s amazing sci-fi thriller is maximal where the original was minimal: BIG explosions, BIG action/suspense scenes, and BIG weaponry. There’s more than one widescreen shot of action and anguish that recalls Jack Kirby’s famous double-truck, post splash-page battle depictions. And the elaborate guns and the giant piece of machinery that Ripley uses to do battle with mama alien at the end: these are designs that could have come straight from the pages of silver-age Marvel epics. The film critic J. Hoberman was one of a very few of his contemporaries to notice the massive Kirby influence Cameron brought to bear here.

“Robocop” (1987)

Some might argue that this manic, gory, venally satisfying satire actually IS adapted, without credit, from a comic book. Certainly its ghoulish premise, wherein a horrifically corrupt corporation raises a wounded cop from near-death by melding him with an advanced robot, owed more than a little to Deathlok, the Doug Moench/Rich Buckler-created character that had a short but memorable run at Marvel in the mid-70s (and has been revived, in less morbid iterations, several times since).

A crucial, and icky, difference: Deathlok merged an actually dead soldier with a computer brain in a post-apocalyptic setting. On the other hand, both characters were from Detroit, too. Hmm. The humorous thrust of “RoboCop” screenwriters’ Edward Neumaier and Michael Miner’s scenario was a little less countercultural than Deathlok writer Moench’s. And the visual punch that Verhoeven brought to the table was drenched in E.C.-like grotesquerie (as in poor Paul McCrane’s melting face when his character receives a much-wished-for comeuppance).

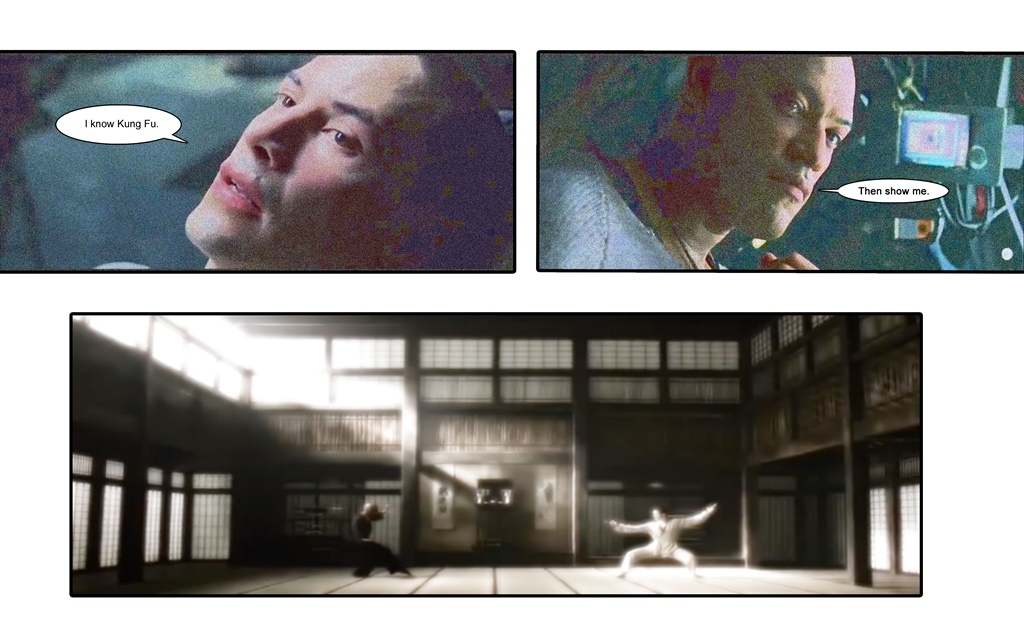

“The Matrix” (1999)

The Wachowski’s mind-blowing trilogy opener merged postmodern philosophy and psychology with cyberpunk fiction and Hong Kong styled action. Its melting pot approach to thought and movement was, at least in this particular film, very counterculture influenced, just as, say, the quasi-underground comic work of Alejandro Jodorowsky and others was in the days of “Metal Hurlant.” Also, Laurence Fishburne proved that if there was ever an actor born to play Galactus, it was probably he.

The movie was such a challenging sell that the Wachowskis actually commissioned genuine comic book artists Geof Darrow and Steve Skroce to draw the thing out for potential producers, concocting 600 pages worth of storyboards. The two “Matrix” sequels, by the lights of some critics, degenerated into the clichéd shoot-em-ups that many unfairly associate with comic books, which are more varied and intellectually advanced than many of the movies overtly based on them have tended to be lately. Not the full circle that many comics fans had hoped for.

(Artwork by John Lichman.)