For a brief period in the late ’70s and early ’80s, Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1978 film “The Marriage of Maria Braun” was the most popular foreign-language movie ever released in the U.S. Yet Fassbinder and the New German Cinema he represented haven’t had the kind of staying power with American audiences as neo-realism and the French New Wave. It’s not that the New German Cinema has been totally forgotten. Werner Herzog’s documentaries continue to find an enthusiastic audience. His 3D “Cave of Forgotten Dreams” was an arthouse hit, as was Wim Wenders’ “Pina.” But the legacy of New German Cinema is more subterranean, as one can tell from the fact that Wenders has found artistic and commercial success since his 1987 “Wings of Desire” only by turning to non-fiction. Fassbinder continues to influence American directors: Todd Haynes (whose “Far From Heaven” owes its existence to Fassbinder’s “Ali: Fear Eats the Soul,” a reworking of Douglas Sirk melodramas), Steven Soderbergh (whose “Behind the Candelabra” owes a similar debt to Fassbinder’s “Fox and His Friends.”) Even Scorsese has worked with his cinematographer Michael Ballhaus. All the same, his films are less frequently revived theatrically than the early work of Godard or Rossellini, and more difficult German filmmakers like Alexander Kluge, Hans-Jürgen Syberberg and Werner Schroeter have been reduced to footnotes.

The five films in Eclipse’s “Early Fassbinder” box set, made between 1969 and 1971, represent only half of the output from an astonishingly prolific period in the director’s work. They aren’t necessarily even the better half. My personal favorite from this period is “Pioneers in Ingolstadt,” although “Beware of a Holy Whore,” included in “Early Fassbinder,” comes close. The debt several of these films owe to American gangster films may make them an easy entrance point for Fassbinder newcomers, although they take these Hollywood reference points strictly on Fassbinder’s terms. He approached film via avant-garde theater—he founded an “anti-theater” group before becoming a filmmaker—and an all-consuming cinephilia. But after discovering Sirk, he vowed to make more accessible films and began working in melodrama, starting with “The Merchant of Four Seasons.”

In Fassbinder’s films, true love and self-destruction go hand in hand. Relationships are almost always manipulative power struggles. While the director proclaimed himself a radical leftist, critic Jonathan Rosenbaum has suggested that his pessimism about change actually makes his films implicitly conservative. A more sympathetic take might suggest that Fassbinder couldn’t see outside his personal pathologies—including the drug abuse that may have fueled his amazingly prolific pace but killed him in 1982—and created a cinematic worldview where his own cruelties and compulsions were universal conditions.

Fassbinder was one of the first directors for whom his own homosexuality was something to be openly declared, rather than a dirty secret. In 1969, that was daring indeed. Apart from “Beware of a Holy Whore,” the gay allusions in the films in “Early Fassbinder” are relatively subtle, but they’re unmistakably present. When Fassbinder did go on to make films with LGBT characters at center stage—”The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant,” “Fox and His Friends,” “In a Year With 13 Moons,” “Querelle”—the nascent gay and lesbian community often reacted negatively. Fassbinder was never one for “positive images” of any kind of sexuality or relationship. It may have taken a media landscape in which more varied depictions of LGBT people are available to see the radicalism of his equally bleak treatment of queer and straight relationships: were heterosexuals an oppressed minority, they’d no doubt object to his depictions of them in films like “The Merchant of Four Seasons” and “Martha.”

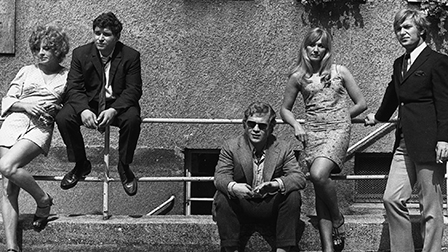

“Love Is Colder Than Death,” Fassbinder’s 1969 debut, seems to be an attempt at subverting the gangster film by injecting large doses of ennui into it. Although far more technically accomplished than Norman Mailer’s “Wild 90,” it conveys the same sense that the actors are superficially playing at being gangsters and cops rather than really disappearing into their roles. For long stretches, pimp Franz (Fassbinder), his friend Bruno (Ulli Lommel) and Franz’s girlfriend Johanna (Hanna Schygulla) seem to be hanging out rather than acting. Many of the sets resemble the blank spaces of empty art galleries. While Franz and Bruno are pushed to join “the syndicate,” they spend far more time shopping, playing pinball or even walking than committing crime. Fassbinder seems completely uninterested in the narrative, yet something about it obviously compelled him. The result is a tedious muddle: half experimental art film (even featuring footage shot by Jean-Marie Straub), half film noir. The misogynist ambiance doesn’t help: the film’s final word is “whore.”

“Katzelmacher” takes place in a Munich suburb where the main pastime is standing outside an apartment complex and bickering about money and sex. The plot really gets underway at the 40-minute mark, when Yorgos (Fassbinder), a Greek immigrant with a limited German vocabulary, moves in. Quickly, he’s suspected of being a Communist and a rapist, while he becomes an object of erotic fascination for some of the local women. “Katzelmacher” contains almost no camera movement, apart from the device of having two characters walk arm-in-arm down the street as a tracking shot follows them. Its origins as a play are evident in the deliberately static quality and reliance on people sitting around talking. The dialogue aims for wit, but it’s rarely laugh-out-loud funny: Yorgos’ incomprehension of German-language insults are the main exception. The idea that xenophobia is rooted in sexual jealousy may be questionable, but given the ugly climate around immigration that persists in the U.S. and Europe, this may be the most politically cogent film in “Early Fassbinder.”

“Gods of the Plague” resembles a film noir on downers. It shows signs of Fassbinder’s literary and cinematic preoccupations: as in “Love Is Colder Than Death,” the protagonist, here played by Harry Baer, is named Franz Walsch, after the main character of Alfred Doblin’s novel “Berlin Alexanderplatz” and director Raoul Walsh. There’s also a nightclub whose name comes from Max Ophüls’ “Lola Montes.” As a narrative, “Gods of the Plague” is relatively classical. Released from jail, Franz gets involved with two women (Hanna Schygulla and future director Margarethe von Trotta) and plans a big supermarket heist with a friend (Günther Kaufmann.) While the cinematography is elegant, Fassbinder had yet to master smooth pacing; the first hour of “Gods of the Plague” comes closer to Jim Jarmusch’s “Stranger Than Paradise” than the French New Wave films that inspired it. Yet there’s something compelling about the film’s experimentation, even if Fassbinder’s skills weren’t all quite there yet. For one thing, “Gods of the Plague” takes a narrative that purportedly revolves around a heterosexual love triangle and turns it in a homoerotic direction, offering up nudity from both Baer and Kaufmann, the latter of whom the director was infatuated with at the time. That’s a twist on the film noir rarely seen even today.

“The American Soldier” is an even more eccentric take on the film noir than “Gods of the Plague.” It follows German-speaking Vietnam vet Ricky (Karl Scheydt) as he returns to Munich and takes up work as a hitman. By this point, Fassbinder’s reference points were starting to feel downright cozy: once again, there’s a character named Franz Walsch (this time played by the director) and a club Lola Montes. There are also characters named after Sam Fuller, F.W. Murnau and New German Cinema rival Rosa von Praunheim. Far more than “Gods of the Plague,” “The American Soldier” feels like a film noir made by someone who’s read about the genre but never actually seen one. The fetishistic attention to costume—fedoras and cheap suits—outdoes Jean-Pierre Melville’s ’60s films. The crime story is hobbled by slow pacing but livened by bursts of flickering lighting, odd camera angles and a memorable final scene in which a character’s death turns into a macabre, endless dance. I think even Fassbinder could sense that he’d hit the end of the road here.

“Beware of a Holy Whore” is the most accomplished of the films featured in “Early Fassbinder.” (It’s also the latest: practice makes perfect.) Structurally, it reprises “Katzelmacher,” with a cast of characters sitting around a Spanish hotel bar waiting for filmmaking to begin. Jeff (Lou Castel), their director, arrives, but his cruelty only rachets up the tension. The film is based on the disastrous shoot of Fassbinder’s Western “Whity,” but it’s one of the most biting examinations of filmmaking ever made. Jeff slaps around women, when not driving his crew crazy. Fassbinder acts here again, playing one of the film’s loudest blowhards. Unlike “Katzelmacher,” it avoids stasis, even when simply depicting people leaning against a bar, through the use of zooms. The film is notable for its casual depiction of gay and bi characters, which was quite rare for the time: people gossip about each other’s sexuality, and Jeff seems to sleep with both men and women. “Beware of a Holy Whore” makes François Truffaut’s “Day For Night,” produced a few years later, look like sanitized pabulum, and paved the way for later treatments of the nastier side of filmmaking like Les Blank’s documentary “Burden of Dreams” and Olivier Assayas’ “Irma Vep,” which paid homage to it by casting a dissolute Castel.