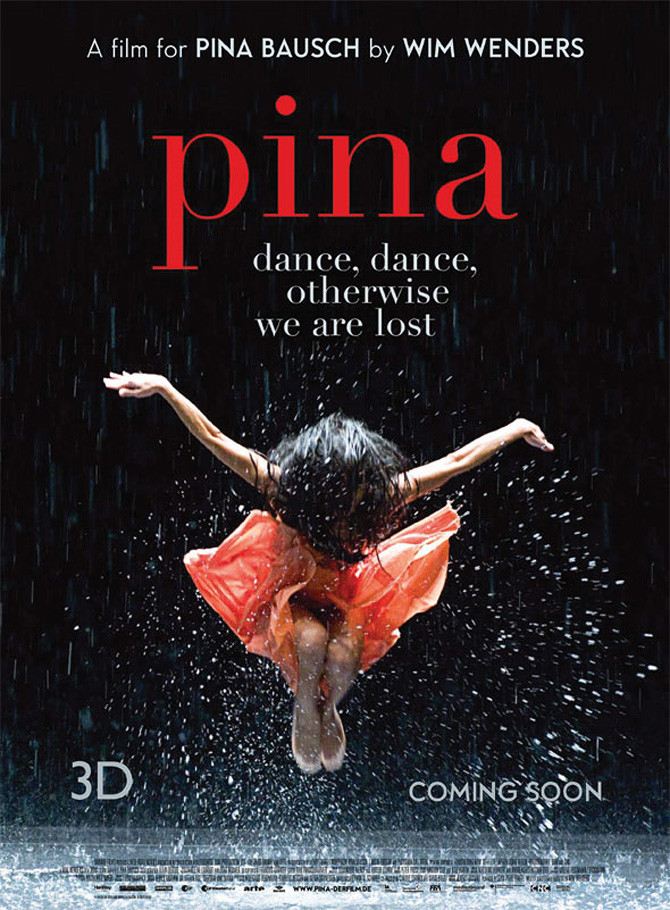

Pina Bausch was a much-loved German choreographer whose work was unlike anybody else’s, incorporating earth, water, stones and city streets into music and movement. She was greatly admired by German director Wim Wenders, who delayed the notion of filming her work until the recent developments in 3-D. It is an irony that as he was preparing “Pina,” the choreographer discovered she had cancer and died a few days before filming began.

Ideally, Pina and her voice would have stood at the center of this film. Hauntingly, it seems to circle the empty space she left behind. There are only a few obviously dated shots of her. And there are the memories of her dancers. Admission to the close ranks of her troupe was an arduous and demanding process, and we sense her dancers are as closely associated as the nuns or monks in a cloister. As they speak of her, their voices are reverential. We do not need to be told she very recently died; we hear the sorrow and shock in their voices.

We do not, indeed, even see them speaking. Wenders uses techniques to set their voices aside from their physical presence. Instead of talking heads, he uses carefully composed closeups, and we hear their thoughts in voiceover. Some look at the camera, some into space. They are young, middle-aged, older, coming from all races, representing (perhaps she thought) the human race.

How can words describe dance? All I can tell you is what I saw. There are four dance pieces here, mixed together, none seen straight from start to finish. One of them, titled “Cafe Mueller,” I remembered seeing in Pedro Almodovar’s “Talk to Her” (2002), in which dancers wander blindly in a room where other dancers rearrange chairs and tables so that in their wanderings they might fall over them. The parallel with life is there to be seen.

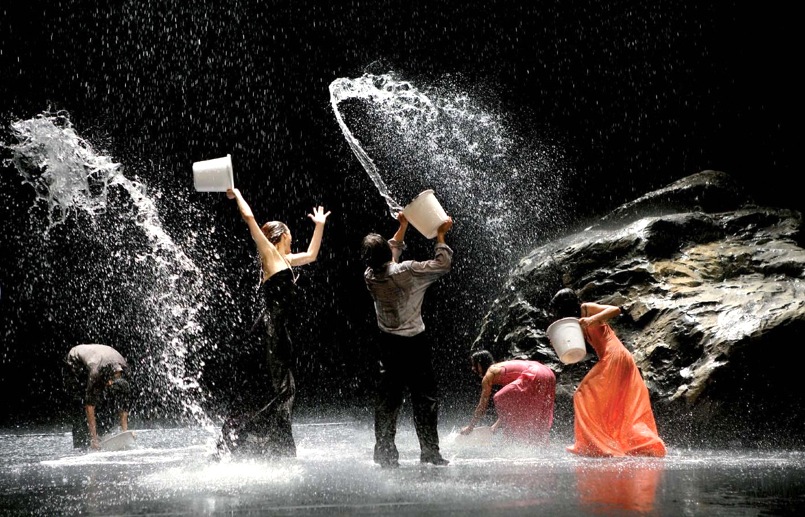

Another uses Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring,” which takes place on a stage covered with earth and sand. Dancers leave traces on this surface as they walk, slide and even crawl on it, and perhaps they represent living things making their way from the soil to the sun. And there is “Vollmond,” with its onstage waterfall. The dancers soak themselves and one another, hurling sprays of water into the air like extensions of their movements.

Wenders has spoken a lot about his use of 3-D here. Like other thoughtful directors (Scorsese, Herzog, Spielberg), he only uses it when he knows why and how it should be employed. Here he visually dramatizes the spaces between the actors by moving his camera on a crane so that the POV places us on the stage and moving among the dancers.

Although Pina Bausch knew Wenders planned to use 3-D, I wonder what she would have thought of the result. Most dance is choreographed to be seen from one point of view, the audience’s. I imagine a choreographer creates it, however, from an omniscient point of view positioned above and among the dancers. That would be necessary to anticipate how the dancers would relate to one another in space; they aren’t cut-out silhouettes, but figures in a landscape. Imagine the difference between ordinary chess and 3-D chess. There are different lines of force.

I watched the film in a sort of reverie. The dancers seemed particularly absorbed. They had performed these dances many times before, but always with Pina Bausch present. Now they were on their own, in homage.