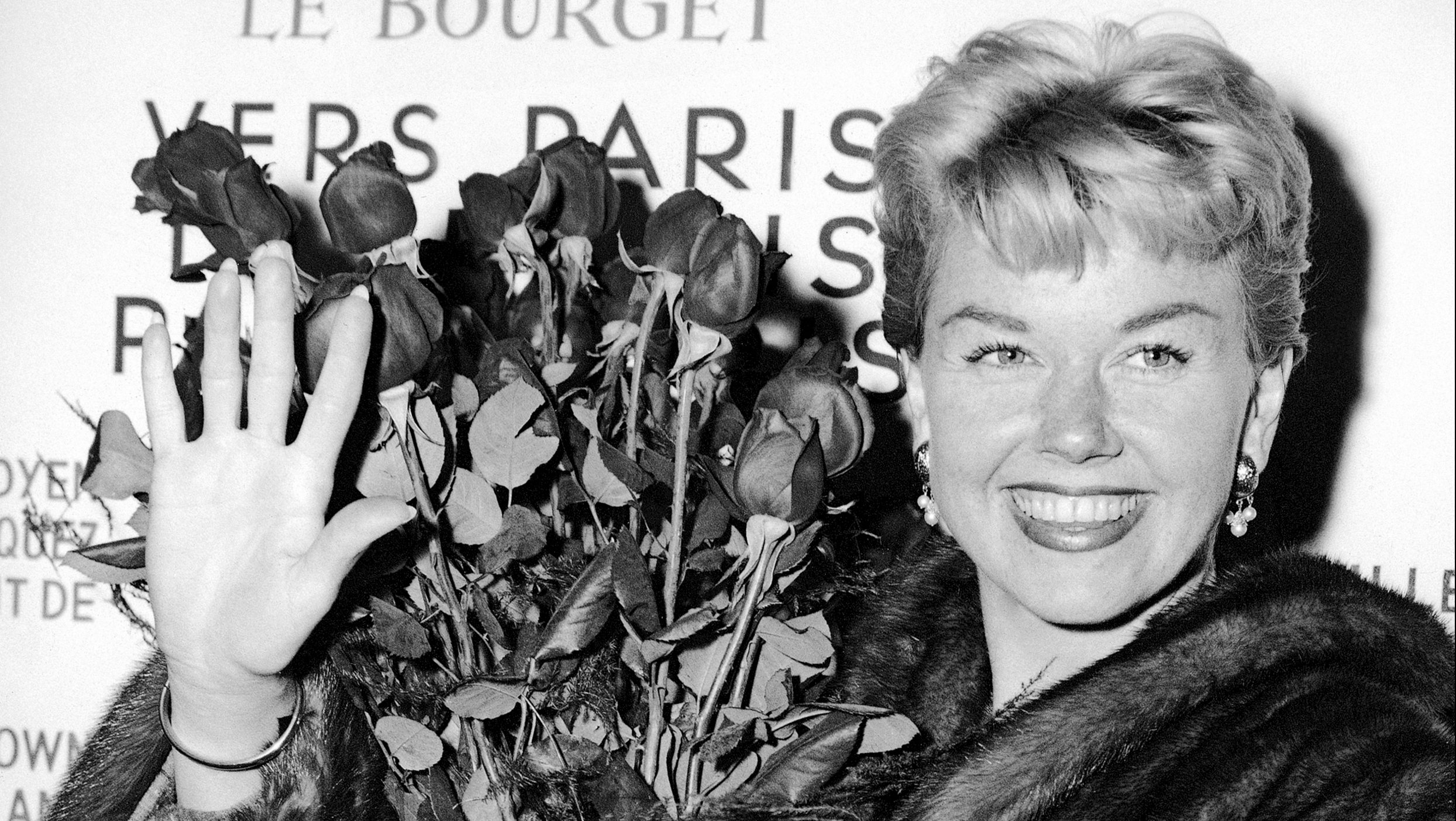

Over her 97 years, Doris Day, who died May 13th of complications from pneumonia, was both revered and reviled for the cornflower-blue eyes and cornsilk blonde hair that reflected her Middle-American roots. It would be an understatement to say that across the board, she struck a profound chord.

Novelist John Updike, a confessed admirer of the actress-singer, wrote the 1996 In the Beauty of the Lilies featuring the Day-inspired actress Alma DeMott as a symbol of an America that has lost its faith but finds something like it at the movies. Pauline Kael, not a fan, dismissed her in the 1960s as a “middle-aged American girl.” For Sarah Vaughan, Day was a favorite singer, while for James Baldwin, she was the quintessence of oblivious white America.

The teenage Big Band singer who became America’s top movie star from 1960 to 1965 was many things. Her much-vaunted wholesomeness was not one of them. Those who looked as well as listened knew she was more spice than sugar.

Never mind that by quipping he knew Doris Day before she was a virgin, Oscar Levant made her a national joke. Others knew her as a national treasure: a contralto who commanded a spectrum of emotions in song, an actress with a dramatic range that spanned the rocky depths of melodramas like “Young at Heart” (1955) and “Love Me or Leave Me” (1957) to the giddy heights of musical comedies such as “Calamity Jane” (1953) and “The Pajama Game” (1957). She had a distinctive catch in her throat that hooked everyone listening. As James Stewart, her co-star in “The Man Who Knew Too Much” (1956), “to put heart in a piece of music is not far removed from acting.”

The daughter of German immigrants to Cincinnati, Doris Mary Ann Von Kappelhoff was born in 1922. Her mother was a pretzel baker, her father the church organist. The family was deeply involved in their Catholic parish until 1935, when her parents split up.

To compensate for the family’s diminished income, Mrs. Von Kappelhoff pushed her daughter onto the stage in local competitions. Young Doris idolized Ginger Rogers—whose younger sister she would play in the 1952 film “Storm Warning”—and spent her after-school hours hoofing like her favorite dancer.

At 14, Doris took first prize in a dance contest that would win her a trip to Hollywood. But the night before leaving she shattered her leg in a car accident. While recuperating she listened to the radio and taught herself to sing by mimicking the voice of Ella Fitzgerald. By 16, she won a spot on a Cincinnati radio show and the following year, a club owner, besotted with her rendition of “Day After Day,” christened her Doris Day. Impressed with her ability to sing as though she directly addressed each listener, bandleader Les Brown hired her. She was 18.

In short order, Day became pregnant and married trombonist Al Jorden, who routinely abused her. She bore a son, named for the hero of the comic strip “Terry and the Pirates.” Soon after she bolted the marriage, parked her son in the care of her mother, and re-upped with Brown. The bandleader ranked her, along with her future “Young at Heart” co-star Frank Sinatra, “as the best in the business.”

In 1943, with Brown’s orchestra she recorded “Sentimental Journey,” putting into words the longings of World War II servicemen dreaming of home. It was her first song to sell a million copies. She became widely known as “the girl with the honey voice.” Soon she was keeping company with George Weidler, a saxophonist. They wed in 1946 and moved to a Los Angeles trailer park. In Day’s memoirs, she writes of being happy to be a homemaker.

The couple needed money, though, so she accepted a gig in New York. Correctly fearing that she would become more successful than he was, Weidler asked for a divorce. Because the studio wanted her for a screen test, Warner Brothers paid for her trip back to Los Angeles. Miss Day accepted the ticket, hoping to change Weidler’s mind. She failed. Stricken, she wept through her screen test for a Michael Curtiz musical called “Romance on the High Seas” (1948). Curtiz liked her unpretentiousness. She lost a husband and gained a studio contract, replacing Judy Garland in the Curtiz film.

While the seemingly sunshiny Day would seem to be the polar opposite of the moody Garland, the two were exact contemporaries with remarkably similar backgrounds. Both were Midwesterners, products of broken homes, with mothers who urged them into show business. As the sole support of their families, both suffered economic anxiety as adolescents. Both would become meal tickets for husbands who spent or misappropriated their earnings. And both had children who would become parent figures to their mothers. Day had Christian Science to sustain her through difficult times.

In her early years at Warners, Day specialized in playing tomboys with pipes in interchangeable musicals like “On Moonlight Bay” and “By the Light of the Silvery Moon,” the kind of girl more likely to have her own toolkit and serenade co-star Gordon McRae than vice-versa. She projected a persona of can-do resilience, as in “Calamity Jane,” as the fabled sharpshooter who dresses and shoots like a man. She is confounded to meet a woman who dresses like one; even more confounded to feel an attraction to Wild Bill Hickock. Her portrait of gender and romantic confusion, both comic and tender, was considerably ahead of its time. “Secret Love,” her song of longing for Hickock, was adopted as a gay ballad. romantic and professional ambition.

In 1951, Miss Day wed Marty Melcher, her agent, who adopted her son, Terry. For the next 17 years he managed—and often micromanaged—her career. Day wanted meatier parts, and was cast in “Young at Heart” (1955) as the troubled wife of the even more troubled Sinatra in a drama of conflicting romantic and professional ambition. Then she appeared as singer Ruth Etting opposite James Cagney as Marty Snyder in “Love Me or Leave Me” (also 1955), perhaps her most stunning dramatic role, as a woman who trades sexual favors for fame. But then again, her follow-up was just as great.

In 1956, Alfred Hitchcock hired her to play the singer in “The Man Who Knew Too Much” opposite James Stewart, as the husband who wants her to give up her career for motherhood. In roles that demanded she play a woman in conflict between work and love, Miss Day had no equal. She likewise played the type in “The Pajama Game” (1957), as a union organizer in love with management (John Raitt), and “Teacher’s Pet” (1958), as a night-school teacher for whom a cynical journalist (Clark Gable) falls for.

Her persona as the working woman who resolves the conflict between love and work got retooled in 1959 when she began a cycle of frothy chastity comedies in which she plays a playboy-taming virgin opposite Rock Hudson (“Pillow Talk” and “Lover, Come Back”) and Cary Grant (“That Touch of Mink”). With these movies, Miss Day dominated the box office until 1965.

When Melcher died in 1968, of cardiac issues untreated medically because of his Christian Science practice, Miss Day’s son, Terry Melcher, took over his mother’s affairs. By then a successful music producer (of The Byrds, among others), Melcher learned that his stepfather had squandered more than $20 million of his mother’s earnings. Not only was she penniless, she owed more than $500,000 to creditors. Even worse: Her husband had used his power of attorney to commit her to a television show without her knowledge. Exactly two decades after her film debut the queen of Hollywood was a widow, broke and legally obligated to a show she deplored.

Reeling from this emotional earthquake, another seismic event destabilized her. Her son and his girlfriend Candice Bergen sublet their Hollywood home to Roman Polanski and Sharon Tate shortly after the younger Melcher had rebuffed an aspiring musician named Charles Manson. The intended victim of the Manson assault on the Hollywood Hills home was Melcher.

She wed for a fourth time in 1976 to restaurant manager Barry Comden. They separated in 1979. He said in court that she preferred to sleep with her dogs than with him, bringing to mind the famous Pedro Almodovar line in “Woman on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown,” that “the more she knew of men, the more she preferred dogs.”

After the divorce from Comden, she moved an estate in Carmel called Casa Loco, personally sheltering and feeding dogs she rescued from the street. Later she founded the Doris Day Animal League.

Though Mike Nichols offered her the role of Mrs. Robinson in “The Graduate” (1968) and Albert Brooks the lead role in “Mother” (1996), Miss Day would not be wooed.

She was predeceased by her son, Terry, who died of melanoma in 2004. She is survived by her shout-outs in songs by The Beatles, Billy Joel, Elton Stephen Sondheim, and Wham!, and by countless housepets.