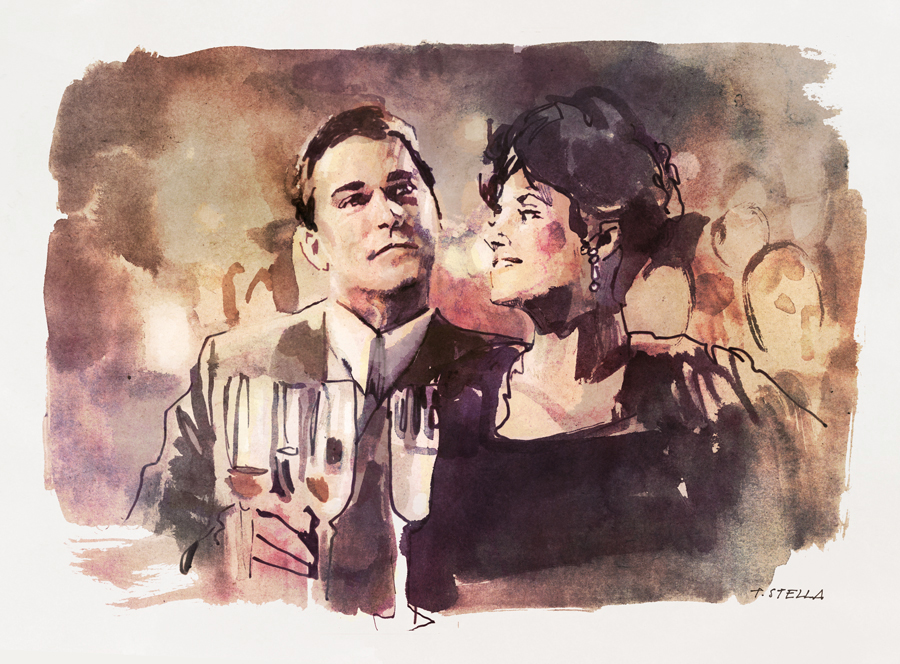

We are pleased to offer an excerpt from the latest edition of the online magazine, Bright Wall/Dark Room. The theme for their September issue is WORK, and in addition to Kellie Herson’s essay below on “Goodfellas,” they”ll also be featuring essays on “Sharp Objects,” “Paterson,” “Support the Girls,” “Five Easy Pieces,” “You Were Never Really Here,” “The Sting,” “Fat City,” “Blue Collar,” “The Hours,” “Mildred Pierce,” “Only Angels Have Wings,” “Beautiful Things,” and “Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy.” The above art is by Tony Stella.

You can read our previous excerpts from the magazine by clicking here. To subscribe to Bright Wall/Dark Room, or look at their most recent essays, click here.

I don’t think the world needs another definitive declaration of what Goodfellas is about. There are far too many, and the vast majority represent a particular viewer’s desire to claim ownership over a cultural phenomenon rather than any substantive effort to engage with the narrative. But since we’re here: it’s a movie about capitalism, or, more specifically, about the way capitalism structures not only our labor and how we get compensated for it, but also our families and our relationships. Every successful mob narrative is on some level a workplace comedy, and Goodfellas is the most incisive one we have. Yes, it’s also about friendships between men, and food, and jealousy, and it offers some tremendous dog content—but the thread holding all those disparate parts together is its comprehensive dissection of the belief that if you get the chance to do a job you love, you’ll never work a day in your life.

That idea is coercive bullshit, of course. Not being miserable at work is something to aspire to, but having a job you love doesn’t magically liberate your labor from its economic or social context, even if that job ostensibly exists outside the bounds of polite society. If anything, love makes it far easier to let your work absorb your life and suck you dry. It doesn’t exempt you from wanting something in return for your work, whether it’s status or money or validation; it just makes it harder to distinguish the things you do joyfully from the things you do transactionally, to figure out the difference between who you are and what you do. It’s like graduate school, if graduate students weren’t quite as into stimulants.

The protagonists of Goodfellas choose their work early in the film because it’s thrilling and fun, because it’s something they love to do, and love to do together. The way these characters sustain themselves is always illegal and often immoral, but their joy is so contagious that I catch myself envying them despite my better judgment. Why, I inevitably ask myself while watching, do my friends and I sit in offices all day when we could be managing a tiki bar that’s a front for other illicit business and then burning it down for the insurance payout? (The answer is, just for the record, Catholic guilt and health insurance. Please let me know if any crime syndicates offer a full benefits package.) At first, the money and respect they accrue seem tangential, an unnecessary bonus. You assume they’d be engaging in theft, assault, and murder anyway as some sort of perverse but exciting group bonding activity.

But their fun decomposes as they get older, and the fantasy of Goodfellas gradually becomes a cautionary tale. Stretching the limits of what they can earn for themselves—whether it’s money or respect or belonging—through these activities becomes all-consuming. Their gradual lurch into the transactional is neither as nihilistic as Casino’s or as hedonistic as The Wolf of Wall Street’s. But it represents a similar effort to excise the rot at the core of events that seem fun and glamorous and aspirational, to expose how people who seem wholly unbound by the rules end up with lives just as limited as the rest of ours. The narrative that emerges here isn’t unsettling because it’s about social deviance; it’s unsettling because it’s deeply normal. Carefree, collective youthfulness gets devoured by individualism and acquisition, unraveling not only these characters’ separate lives but their relationships with one another. By the time Jimmy, who loves to steal, nears the end of his career, he can’t even enjoy executing the most impressive theft in American history. The success leaves him miserable, consumed by paranoia that anyone involved could send the whole thing tumbling down. These characters constantly expand their wealth and their influence, but none of them can ever have the specific kind of power they want—Jimmy and Tommy, in particular, can never become made men. And this perpetual dissatisfaction becomes the core of what motivates them, gradually replacing the love and excitement that once sucked them in.

Of course this journey into the mercenary shapes both the collective and the individual rises and falls of Henry, Jimmy, and Tommy. But for me, the film’s most compelling window into how people struggle to navigate a system that depends on constantly striving for something that’s always held just slightly out of reach is Karen Hill’s journey from (hilariously bored) date to wife to unofficial business partner. It’s a thread some viewers lose—and, to be fair, there’s a lot going on here and the run time is, like that of every Scorsese film, at least a hair too long; it’s easy to hold onto the scenes that stand most memorably on their own and forget the larger narrative context. But I’m always fascinated by her, and left struggling to separate out the things she does for money from the things she does for love, to mark where her desire for things she can never have ends and her resigned willingness to grab whatever she can get begins.

In fact, I would argue that her development is the backbone of Goodfellas, the piece that enables much of its thematic and emotional heft. It’s a narrative achievement, of course, but most of the credit belongs to Lorraine Bracco, whose performance is one of my all-time favorites: funny and charming, dark and terrifying, sometimes all of these things at once. Through her, we get to know Karen’s point of view better than any other characters’, and through Karen, we get to understand what it’s like to be simultaneously inside and outside the illegal, immoral, and violent work the movie depicts. Her perspective lends the movie much of its complexity and nuance—not just because her voice-overs frame so many pivotal moments, but because her narration so compellingly contradicts not only itself but also what we watch her see. When she tells us that Henry and his friends are “just blue-collar guys,” gaming the capitalist system, it’s not an effort to convince us but to convince herself. She’s close enough to see what’s happening, distant enough that she can recognize that it’s spiraling out of control, and embedded enough to have a vested interest in talking herself out of that recognition. Her domestic labor is inseparable from but not identical to her husband’s criminal labor, and her negotiation of her own complicity swings wildly between mercenary pragmatism and hopeful idealism.

You could read her constantly shifting relationship to her work as unrealistic character development, or interpret her inconsistency as yet another troubling entry into the “Bitches Be Crazy” canon—or you can understand her as a liminal subject trying to navigate an overwhelming context with mixed results. Her journey is not so much a straightforward arc from idealism into greed as it is a messy recursive process, a constant cycle of learning and unlearning and relearning how to get by as a woman who supports and is supported by this particular work. In a less biting movie, Karen would be a well-behaved middle-class Jewish girl corrupted by a criminal husband; in a Scorsese movie, the boundary between polite society and its criminal underbelly is far too blurred for such simplicity.

From the beginning of Karen and Henry’s relationship, love and acquisition are hard to separate from one another. She loathes him instantly, identifying him as a selfish dirtbag and spending their first double-date wearing an expression that I am, as a sufferer myself, both allowed and required to note is a god-tier achievement in resting bitch face. But the moment Henry signals that he’s unattainable, she must correct this, hunting him down in the street to yell at him. And while she’s intrigued by the expensive dates that follow, she doesn’t fully commit to loving Henry until he pistol-whips the man who sexually assaults her and then asks her to hide the gun. That decision—and it feels like just that, a decision, albeit one in which desire is included in her calculations—captures exactly what being attracted to an asshole entails. It’s a combination of the hope that his unearned confidence wears off on you, the validation of occasionally being the exception to the rule of how badly he treats people, and the thrill of getting to borrow that bad behavior for your own ends.

But even after this decision is formalized at their wedding, she still harbors reservations about Henry. She’s always evaluating her surroundings, trying to determine whether this life is worth what she receives in exchange for participating in it. Whenever she verbalizes her fear that the trade-off isn’t worth it—a fear that often emerges from her awareness that she will never fully belong—Henry talks her out of it. And as Henry grows more absent, she takes over this responsibility, talking herself out of everything she knows. Her rationalizations of her role in her husband’s work aren’t a regurgitation of things he’s told her previously; her explanations are far more nuanced and observant than his, grounded not in the desire to have an exceptional life but the need to hang onto a normal one. Her rationalizations offer a way of making her life livable, of holding onto the hope that she might get what she wants from adulthood—but they serve a meta-purpose as well, exposing the logic the film critiques and revealing the ways we convince ourselves to comply with our own destruction.

Karen’s compliance is never permanent, of course. She can explain in meticulous detail how her husband games the capitalist system, but she still knows what she knows. And the most urgent thing she knows is that the things she wants in exchange for her work—some influence, but also some loyalty, some kindness—are never going to take shape. Henry fails to be reliable in any capacity beyond the material: he lies to her, cheats on her, gaslights her, and leaves her isolated for long stretches of time, sometimes because he’s incarcerated but other times because he just feels like having more fun elsewhere. The only power she can leverage is the fact that her husband’s colleagues are terrified of her—because while Henry has compartmentalized her away into a very small section of his expansive personal life, his friends already know she’s part of their enterprise. Of course, this minimal power is not enough to get her what she wants; even if it did, the fact that this is her one small measure of influence still reveals the extent to which her life is interwoven with her husband’s violence and greed.

As Goodfellas nears its end, Karen seems resigned to her perpetual dissatisfaction, treating her marriage like a miserable job at a floundering company and grabbing whatever she can get before it goes under. She has every material possession she could want—an expansive wardrobe, free cocaine, a truly hideous remote-controlled rock wall—but this glamorous excess is contradicted by the empty affect of someone who’s just trying to get through a workday. As Henry’s solo business reaps more and more chaos, she gives up trying to assert herself or find a coherent explanation for anything; she is, in a few scenes, literally just along for the ride. No one in the history of cinema has ever come down with such a severe case of the fuck-its.

And yet when everything implodes, she comes alive again—briefly. As her husband is arrested and her home is surrounded by police, she disposes of everything that could incriminate him. It’s an act of love, or at least one of loyalty; it once again makes her complicit in Henry’s business, but it also protects Henry and their family. But when Henry learns what she’s done, he’s not grateful, just furious that she flushed $60,000 of cocaine down the toilet. His reaction lays bare the void at the core of their marriage, the extent to which their conflation of love and money turns even acts of pure, irrational loyalty into a question of exchange value. She sees it clearly, but it’s far too late to extricate herself; even Henry selling out his friends, entering witness protection, and leaving his work behind doesn’t grant her a way out. His job has ended, but hers has not. Just like the men she’s surrounded by, she loved it once—and we know, finally, that love, not money or glamour or interminably delayed gratification, is the force that allows her work to consume her life.