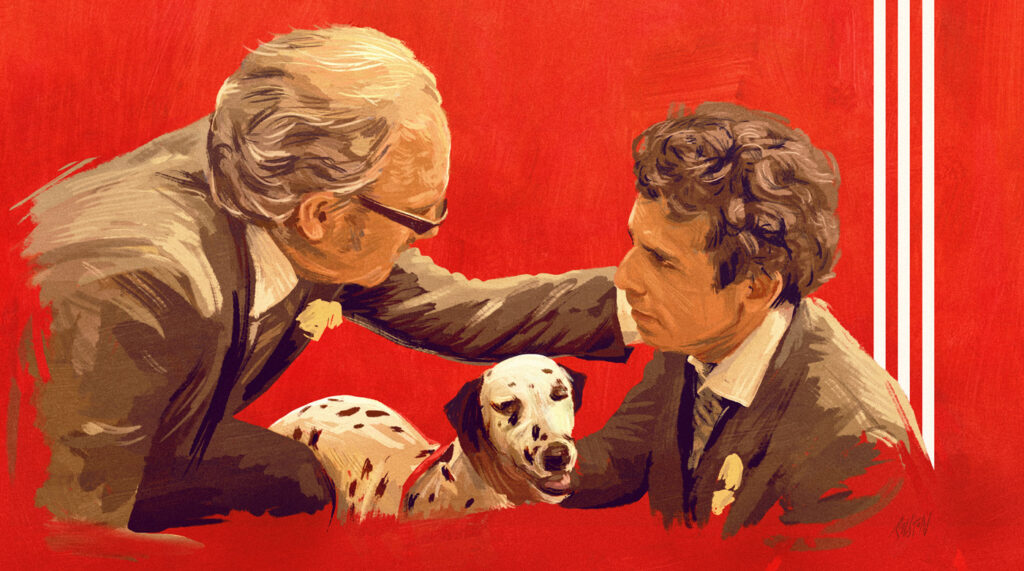

We are pleased to offer an excerpt from the December 2021 edition of the online magazine Bright Wall/Dark Room. Their theme this month is “FUBAR.” In addition to the excerpted essay below on “The Royal Tenenbaums” by Matt Chambless (with artwork above by Tom Ralson), the new issue also features new essays on “Manhunter,” “Batman Returns,” “Don't Look Now,” “The English Patient,” “Wild Mountain Thyme,” “8 Million Ways to Die,” “Othello,” “Bitter Lake,” and “Fail Safe”.

You can read our previous excerpts from the magazine by clicking here. To subscribe to Bright Wall/Dark Room, or look at their most recent essays, click here.

Through the years, I’ve adopted a sort of ticklish preoccupation with the brute-force manner with which we announce the death of our public figures. PRINCE DEAD AT 57, for instance. Dead, in this context, unnerves me; it arrives before I’m ready. The expediency of the language teetering on impertinence. And though we can’t ignore it, can we at least soften the blow a little?

PRINCE GONE AT 57.

PRINCE PASSES AWAY AT 57.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately, about loss and death and obituaries, and about my father. My father died this past August, and though I didn’t write his obituary, I did deliver his eulogy. Standing in front of friends and family, I recounted what it was like growing up with him in the middle-class suburban home we occupied with my mom. I let them into the world of music that would so often fill our house, and the nights where we all went to the theater together. After the service, I found myself surrounded by those who wanted to indulge a little longer—to get a second chuckle at the time he was robbed at gunpoint (I told it funny, you had to be there), or to confess that, as well as they knew him, they never knew that he once wanted to be a professional fisherman. On and on like this it went, each person thanking me for standing up and sharing the memories of my father. But the dirty little secret is that those were all his memories. Which is to say, they were a small collection of the stories I had heard him tell over the years. I merely repeated them.

Throughout his life, my dad was many things—a Marine, an actor, a musician, and more—but my favorite, and the one I wanted to honor most that day, was storyteller. In the hours and days after his passing, as the phone calls came pouring in, I couldn’t help but notice that everyone who reached out, without fail, in one way or another, told me just how much they loved listening to the stories of my father. That was my dad: he’d talk to anyone who’d listen, regaling them with the adventures of his life. And he loved having stories acted out for him as much as he loved telling them. This started at an early age, crouched beneath the family radio listening to episodes of The Lone Ranger, or spending countless weekends eyes-glued to whatever western was showing at the neighborhood cinema. Once I came along, he passed that love on to me as if by birthright. Whether it was letting me stay up past my bedtime to watch The Godfather for the first time, or introducing me to Young Frankenstein on a family vacation, on and on like this it would go throughout the rest of our lives together, he and I honing the dominant language we spoke to one another—the language of film.

Now, without him, I’ve been trying to reorient myself and my relationship to the movies, in the hopes that, through them, I might still be able to communicate with my father. I think they will always carry, though, some reminder of loss, and death, and the end of an innocence that only comes after losing a parent—and the long, lonely work of gathering the scattered pieces of all that remains in the hopes that, one day, I might know what to do with them. And so, in this moment, when the way forward seems so daunting and unknowable it can only be approached by metaphor, and the path of extrication from this forest of grief has not yet made itself visible—except perhaps to the keen eyes of certain mystics and select Upper West side analysts—I turn to the only scripture I know, the only way I can think to wrap my head and my heart around what has happened. Naturally, I’m referring to Wes Anderson’s third feature film, 2001’s The Royal Tenenbaums.

Let me explain.

First, let me say that when I think of The Royal Tenenbaums, I think of it as a Ben Stiller film. Which isn’t exactly right, but it isn’t exactly wrong, either. Inherently, it’s an ensemble movie with at least one, if not many, indelible moments given to each of its superbly cast actors; in this way, it is anyone’s film. But there’s something tragically tangible woven into the character of Chas Tenenbaum (Stiller) that transcends the blurry outer reaches of where our natural world ends, and the whimsical surrealism of a Wes Anderson universe begins. Something so discernible, even, we might easily mistake Chas as someone capable of populating the neighborhoods of our own reality. And this characteristic is present in many of the characters Ben Stiller chooses to portray—that of being the agents of their own chaos. From addiction in Permanent Midnight, to absurd hubris in Dodgeball, to the cringe-worthy comedy of errors in Meet the Parents, Stiller continuously, and often quite spectacularly, makes homes in these distinctly flawed individuals.

Of course, he wasn’t the first to play this particular trait upon the silver screen, and he arguably isn’t even the first to do it in this movie (that distinction goes to Gene Hackman’s Royal Tenenbaum, depending on how you’re scoring at home). But what makes Chas’ storyline, and by extension Stiller’s performance, so tender and tragic is the ripple effect that connects the broken relationship with his father—a relationship that results in his emotional and physical abandonment during childhood—to the spiral we find him in as an adult after his wife’s untimely death. At every stage of development, the important relationships in Chas’ life, the ones he should be able to count on the most, are taken away from him. It’s no wonder he has his two young boys, Ari and Uzi, running safety drills in the middle of the night; if life has taught him anything, it’s to expect the eventual loss of everyone closest to him. And as such, you might forgive the chaotic and emotional tailspin Chas has locked himself into for most of the film. Yet it’s precisely in this psychological isolation that lies his signature character trait, the one that’s brought Ben Stiller to the proverbial yard. Yes, Chas’ father walked out on him. Yes, life dealt him an unnecessary blow by taking his wife, too. But in what’s most likely an act of self-defense, whether consciously or not, Chas has become the agent of his own chaos, perpetuating the emotional gulf between himself and anyone meaningful in his life, so as to never have to feel loss or betrayal again. And in doing so, he’s living in suspended animation, arresting any hope of healing, unable to withstand the heavy weight of life’s downward thrust.

*

Wesley Wales Anderson was born in Houston, Texas, the middle of three boys, to an adman father and a realtor and archeologist mother. By the age of eight, his parents had divorced. Much has been made of this. Any cursory watch of Anderson’s films will reveal frequent variations on dysfunctional father/son relationships (and if not fathers, then father-like figures); a quick Google search returns countless think pieces opining the various ways Anderson himself must have been hurt by his own father. The Royal Tenenbaums is not immune to this, though the film is not autobiographical. One of the great distinctions of Anderson’s artistry is his ability to so thoroughly camouflage his references, molding them into his signature style; present though they may be, you can’t argue he hasn’t made them his. Drawing from such films as Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons and Louis Malle’s The Fire Within (from which he borrows the line, “I’m going to kill myself tomorrow”), Anderson takes a long, and quite enjoyable, lap through ruminations on loss, redemption, broken family dynamics, and betrayal. What makes the film so rich is that each of its primary characters seems to be going through something, giving sufficient time and energy to weaving their lives and storylines through these thematic ideas. All the children, once thought to have been geniuses, have aged into shells of their former selves. Royal, having lost his family—primarily of his own devices—seems to be warming to the idea of getting them back. Etheline, having lost a husband, and then a string of suitors, is trying to grab hold of any sense of stability and happiness. Raleigh St. Clair has lost his wife; Dudley, his ability to tell time; Royal, again, his javelina. It’s what makes the film enjoyable: there are no wasted character strokes. And it’s also what makes the arcs of the characters’ redemptions so satisfying.

But in the midst of all of that, the one dynamic that feels the most honest, the least gilded, and therefore, perhaps, the most personal, is the one between Chas and Royal Tenenbaum. The obviousness of the father-shaped hole in Chas’ life, especially when one is needed most, makes the Chas/Royal/father/son relationship, for me, the true emotional center, and the more poignant will they/won’t they relationship of the film (with apologies to Richie and Margot’s is it/is it not incestuous love affair). The culmination of this tension comes just before the film’s epilogue, at the marriage of Etheline Tenenbaum to Henry Sherman, where family friend Eli Cash—himself in a mescaline-induced tailspin—crashes his car into the side of the Tenenbaum house, nearly killing Chas’ two young sons were it not for the heroics of Royal. Chas’ worst fears are almost realized, again: the eventual loss of those closest to him. Their near death—and the actual death of the family dog, Buckley—ultimately proves too much, setting Chas to violently chase Eli throughout the house and into the backyard, where he corners Eli and tosses him over a brick wall into the neighbor’s rock garden, letting loose a primal yell. The family looks on in shock. It’s an out-of-body experience for Chas, and you can see him returning to himself as he stands in judgment of what he’s just done. Then, perhaps in shame, perhaps by way of his own banishment, Chas climbs over the wall and lays down next to Eli, and confesses that he, too, needs help. It’s a moment where the audience and characters alike have finally arrived at the same conclusion: Chas is not well.

Then, one of the smallest and most important moments of the film occurs, the crux of its emotional arc. Anderson builds to it through one of my favorite uses of montage, dollying the camera along the length of a fire truck from vignette to vignette like panels in a comic strip, each one a humorous quip, or callback, or culmination to some previous joke or character’s backstory. As the camera progresses, sandwiched into the middle of this montage, we see Royal, who has nearly completed his rehabilitation back into the family’s good graces, questioning two firemen on the provenance of their Dalmatian. It’s a quintessentially Anderson moment; it’s not exactly funny, and not exactly serious, either, but there’s certainly a kind of amusement to it. It’s angular and wonky in all those perfectly Andersonian ways. But unlike the other vignettes, this is not a button on some previously illuminated character trait or relationship. It’s not until a few seconds later, when Royal reappears at the end of the montage, that his actions are fully made clear: he has negotiated the purchase of the Dalmatian—named Sparkplug—to replace the recently deceased Buckley.

And this brings about the last door through which Royal must walk to complete his redemptive arc: his reconciliation with Chas. It just so happens that Chas needs this, too, even more so than Royal. And so there the two of them are, standing face to face, Royal apologizing for not being there for Chas, and for the family, and earnestly trying to make up for it. They crouch down together, Chas gives Sparkplug a little pet on the head, and then it happens: Chas takes a breath, drops his armor, and says the most vulnerable and beautiful line of the film, “I’ve had a rough year, dad.” After a lifetime of denying it, and after the course of his life has rippled in directions unimaginable, Chas finally says to his father, I need you, too.

It’s a tender moment expertly portrayed by both actors. You can feel the exhale between the two of them as Royal replies, “I know you have, Chassie.” I love everything about it and the roughly 97 minutes it takes in getting to it; nothing more so, however, than the five seconds of silence just before he breaks down and utters the line. It’s an inflection point for Chas—the culmination of 20 years of scar tissue—and with each tick of the clock, he questions whether to continue his one-man war against his dad (Richie and Margot having already made their peace, at least in part) or to finally lay down his armament and admit his vulnerability aloud to both himself and his father.

Those five seconds pose as a kind of silent film parallel to another one of my favorite father/son moments in cinema: Inigo Montoya’s revenge against Count Rugen, aka the six-fingered man, in The Princess Bride. In the culmination of that storyline, after Inigo’s lifelong search for Rugen—the man who killed his father—he finally gets his chance at exacting revenge in a sword fight to the death. And then Inigo, having bested the Count and now standing with his sword poised to deliver the fatal blow, suddenly offers him a chance to spare his life. He asks the Count to promise him whatever he wants in return for letting him go, and the Count dutifully obliges, offering him power, riches, anything he’d like. To which Inigo responds, “I want my father back, you son of a bitch,” and stabs him in the stomach.

For me, in those five seconds just before Chas responds to his dad, he’s not unlike Inigo trying to best the man that took away his father (or, more accurately in Chas’ case, the man who is keeping his father just out of reach). But he is also not unlike the Count, which is to say that he is both the one who misses his father and the one who stands in the way of ever getting him back. In those last few breaths of silence, he finally confronts the part of himself keeping his dad at arm’s length, and musters the courage to stab all his fears and anxieties in the belly so that he might look up and see his dad, as he really is, standing before him, for the first time in a very long time.

*

“Matthew, get up—we have to go,” my mom said as she jostled me awake.

My father’s health was in steady decline, and I had come home from Los Angeles to be with him. Sometime after midnight, on his last night, a nurse called telling us to come quickly if we wanted to be there for it—which we did—and so I rose, dressed, and drove my mom and I the 17 miles back to the hospital. The streets were silent and gripped with fog, not unlike the two of us. He died at 1:50 a.m. I was standing by his side.

It’s that last part I think about often. The being next to him. The looking down at his hands, at his chest rising and falling, and wondering when it might happen; at his face, so peaceful, and thinking, Is this the last moment I’ll ever get to see it before he travels on to whatever is next—or is it this moment, or this one?

I was lucky in that I got to prepare; though the end seemed sudden, my dad had been sick for years. According to psychological opinion, this is the preferred context for losing a parent: the less unexpected death. And though the contours of each individual’s grief may vary, there is a certain significance in sons witnessing their father’s death; a comfort in knowing that they were there at that moment in time, standing in just the right place. I can’t help but feel that The Royal Tenenbaums, too, at least on this, agrees with me.

At the age of 68, Royal has a fatal heart attack. The only witness to his death: Chas. It would be too easy to view this as the only fitting eventuality to the reconciliation we just witnessed. That would cheapen the significance of a moment between father and son that almost didn’t happen. A moment that wasn’t preordained just because it was written on a page in a script, but had to be earned by two individuals who inhabited a world not unlike our own. My perspective on this—on Chas’ arc—has changed as a result of my father’s death. I used to take Chas’ presence in the ambulance alongside Royal as they raced towards the hospital for granted. I no longer do. Instead, I feel grateful that he was able to be there in those last moments because it means that, for whatever time he was afforded, he got to have his father back. In that way, for me, The Royal Tenenbaums has transmuted genres, occupying, instead, the halls of magical realism. Chas’ one beautiful line to his father: a passphrase; an elixir; a genie that grants wishes.

In this fashion, Tenenbaums has become my own father-finding Zoltar machine, an oracle communing with the other side, offering the line “I’ve had a rough year, dad” as a prayer so that, when recited, I too might have my father back. There is beauty in this, but also an inherent risk. At best, the film occupies for me a kind of liminal space—the threshold between what has passed and the unknowable next—where, as the Franciscan priest Richard Rohr believes, “the bigger world is revealed.” Rooted in this, however, is an intrinsic motility. To be in a state of transition, one must move. Chas, by contrast, experiences grief motionless, stuck in the bardo between bargaining and acceptance. And therein lies the risk, the risk of knowing which grief I possess—am I in motion, or am I static? By granting Chas’ line its power, have I entered into a bargain, or found acceptance? Am I becoming the agent of my own chaos? Would I even know the difference?