The opening ten minutes of Michael Mann’s “Thief” remains one of the most influential sequences in movie history. Inspired by similar set pieces in the heist thrillers “Rififi” and “Topkapi,” it’s an almost silent sequence that’s groundbreaking in its visual and aural components. Mann and cinematographer Donald Thorin envision a nighttime cityscape of sharp angles, wet streets, and sinister neon lighting. We watch as Frank (James Caan) and his tight crew of professional thieves penetrate an office and use high-tech gear to break into a safe. (Frank only steals ice or money.) The precision of Frank and his crew is mirrored by Mann’s direction. There’s so much confidence on display that we never worry about anyone getting caught.

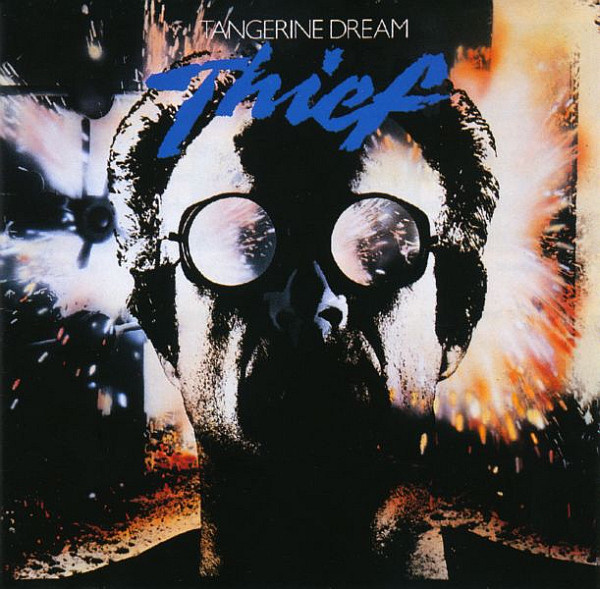

The sequence is held together by an electronic score from Tangerine Dream. An outfit out of Germany, Tangerine Dream was a product of the “Krautrock” and Prog rock movements. Bands like Kraftwerk, King Crimson, and Yes expanded the pop song form. Songs like Yes’ “Heart of the Sunrise” and King Crimson’s “21st Century Schizoid Man” were expansive. Their long instrumental interludes would have subtle variations. (Just listen and marvel at the first three minutes of Yes’ “Heart of the Sunrise.”) Building off these early innovations, Tangerine Dream specialized in synth-pop symphonies that washed over the listener. The first movie score they composed was for William Friedkin’s 1977 remake of “The Wages of Fear,” retitled “Sorcerer.” It was a good score that distinguished the movie, but it didn’t leave a mark like “Thief.”

The centerpiece of the score is the epic “Diamond Diary,” a ten-minute-plus piece heard in the opening sequence. It begins with a simple, single synthesizer note and quickly adds layers upon layers, ebbing and flowing with tension and rhythm. When Frank cracks open the safe the music slightly accelerates its tempo. The difference between extended instrumental jams by bands like Humble Pie or songs like Led Zeppelin’s “Moby Dick,” and the work of groups like Tangerine Dream is there is rarely any variation in the music. The jam is designed as a showcase for a particular musician. The song quickly becomes monotonous, one-note. Not so with the music of Tangerine Dream. At one point, a pivotal key change in the score is signaled when Frank lights a cigarette while driving. The forward, propulsive rhythm of the score is mirrored by the forward motion of driving at night.

The other great track comes toward the end when Frank, backed into a corner, decides he must burn everything to the ground to regain his freedom. “Dr. Destructo” is a menacing piece of synth-rock, complete with a strutting beat that acts like a countdown to annihilation. The final track—the only non-Tangerine Dream piece in the main score—is a Craig Safan piece entitled “Confrontation,” a mournful cue that signals how much Frank has given up in order to be free. (Mann wanted Pink Floyd’s “Comfortably Numb” for this sequence but couldn’t get the rights; Safan’s piece sounds like a lawsuit-proof approximation.)

Audiences didn’t know what to make of “Thief” or its score”—Mann’s film was not a financial success, and Tangerine Dream’s score was nominated for Worst Movie Score at the Razzies. But the long arc of movie history validates the both director and the band. Released nine months before “Chariots of Fire,” a film with an Oscar-winning synth score by Vangelis that was more upbeat and inspirational, “Thief” broke down the doors for synth scores in mainstream film, and had a ripple effect on the rest of pop music.

The immediate impact of the “Thief” score could be heard on the radio, in tracks by bands like Haircut 100 and on songs like Duran Duran’s “Rio,” (especially with its grand synth intro). New Order transformed the synth rhythms of Tangerine Dream into enveloping dance beats. Songs like “Blue Monday” have a percolating beat that recalls Tangerine Dream and early Kraftwerk. But the most successful outfit to be influenced by Tangerine Dream is Daft Punk, whose recent announcement of disbanding left a hole in the music world. Their combination of synth-pop, trance, and disco created a sound that was at once original and retro. Songs like “Around the World” and “One More Time” spoke to a vision of an era in which technology had taken over but humanity still survived. (Was it any surprise that they did the score for “Tron Legacy”?)

As for Tangerine Dream, they became the hip, go-to movie composers for a brief moment. Writer/director Paul Brickman used their music as score for his suburban-teen capitalist satire “Risky Business.” Released in the backwash of countless brainless, sexist teen sex comedies, “Risky Business” was a sharp-edged Reagan-era update of “The Graduate,” set, like “Thief,” in Chicago, with its main location the sort of suburban mansion where Robert Prosky’s Leo might lord it over his subordinates. The score—particularly a track entitled “Love on a Train”—elevated the movie out of the teen-sex comedy basement and gave it an artsy cache. Even the song selections had an art-rock sensibility. Pieces like Talking Heads’ “Swamp” and Prince’s “D.M.S.R.” fit in with the Tangerine Dream score. But the movie’s best song selection is Phil Collins’ “In the Air Tonight,” a synth-pop rock ballad that is startlingly of a piece with the work of Tangerine Dream. (It’s probably no coincidence that it was prominently used in the 1984 pilot for “Miami Vice,” a cop drama executive produced by Michael Mann.)

After that, Tangerine Dream’s movie scores were less effective. Their score for Mark Lester’s 1984 Stephen King adaption “Firestarter” is moody and fun but a bit familiar. By the time they did the replacement score for Ridley Scott’s “Legend” (displacing Jerry Goldsmith, whose original score played prints in Europe) it was clear that Hollywood moved on.

Surprisingly, Mann only used Tangerine Dream once again, on “The Keep”—a commercial flop that was practically memory-holed for a while—but he did continue to use synth scores. In “Manhunter,” composer Michael Rubini’s haunting score is accentuated by synth-rock tracks like The Reds’ “Heartbeat” and The Prime Movers’ “Strong As I Am.” The masterstroke comes during the movie’s extended climax, which is scored to the granddaddy of acid-prog-rock anthems, Iron Butterfly’s “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida.” Mann would get even more experimental with his soundtrack for his epic cops-and-robbers drama “Heat.” That synth-orchestral score is composed by Elliot Goldenthal, but the bulk of the score comes from previously recorded tracks from the likes of Brian Eno, Moby, and U2 side project Passengers.

The most iconic piece of music in Mann’s “Heat” is Eno’s “Force Marker,” an electronic-percussive piece that scores the centerpiece bank heist. Like “Diamond Diary” from the opening heist sequence of “Thief,” the track conveys forward motion. Moby’s synth-rock grinder “New Dawn Fades” is used as a preamble to Detective Vincent Hanna (Al Pacino) confronting master thief Neil McCauley (Robert DeNiro) right before they have a cup of coffee. The final piece of music is even better, Moby’s “God Moving Over the Face of the Waters.” It comes after a cat-and-mouse shoot-out between Hanna and McCauley and the two men share a moment of acceptance and understanding. Its piano-driven orchestration has an almost ethereal quality, as if suggesting something spiritual has passed between the two men. It’s the Dream-iest of all the tracks in the film.

And what about Tangerine Dream? Their popularity grew because of their scores for “Thief” and “Risky Business, two scores that meant they would always have sell-out shows around the world. (The group still performs from time to time, although founding member Edgar Froese passed in 2015.) Like most things that are original and innovative, the majority of the imitations are bad. Although synth scores have enjoyed a resurgence in the past decade, as evidenced by everything from Netflix’s “Stranger Things” to “Drive” to the documentary “Apollo 11” and director-musician John Carpenter’s live appearances, the recent film that has displayed the most intriguing affinity for “Thief” is the Safdie brothers’ “Uncut Gems.” More of a character study than a crime story, the movie stars Adam Sandler in a career-capping performance as a gambling addict and diamond salesman trying to erase his debts by making more and larger bets. The synth-orchestral score by Daniel Lopatin jacked up the film’s already considerable anxiety level. As in “Thief,” its constant presence infuses the movie’s so-called quiet scenes with tension. It’s a dream of things to come.