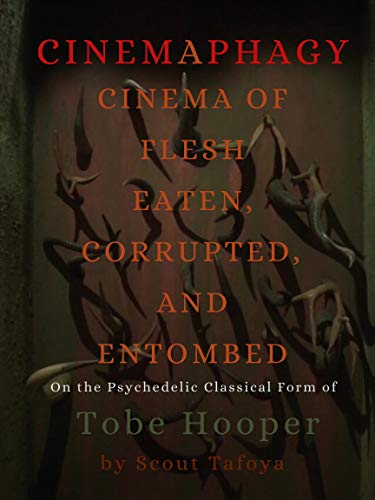

We are incredibly proud to present an excerpt from the new book by Scout Tafoya, the man behind the Unloved series here at RogerEbert.com. You can find the official synopsis and a trailer for the book below. Get your copy here.

He directed “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre,” the most infamous and visceral horror film of all time. He directed “Poltergeist,” one of the most successful ghost stories of the 20th century. He was called a Master of Horror and he worked with screen legends James Mason, Neville Brand, Karen Black, Fred Willard, Dennis Hopper, Anthony Perkins, Mel Ferrer & Marie Windsor. He elegantly navigated the works of pulp legends Ambrose Bierce, Stephen King, Cornell Woolrich, & Richard Matheson. And yet Tobe Hooper is one of the most unsung film artists of the last 50 years. How did the man famous for creating some of the most endearing images of terrible things, who did for the hardware store what Jaws did for the beach, become someone in need of rescue?

Cinemaphagy is the study of an artist’s working life, his bountiful creativity, his ardent cinephilia, his prolific career in film and television, his lasting influence beyond the saw. Horror movie directors are too frequently pigeonholed as purveyors of the macabre, but in truth Hooper was one of the most boldly experimental genre filmmakers in the game, fusing a Texan psychedelia with an earnest classical style gleaned from years watching classic films. Hooper’s life and work is like four years of film school, and every film he made, no matter how thankless, no matter how silly the assignment on paper, became a rich, roiling text on the political underside of the American cinema. No one made movies about cinema less ostentatiously and with more love. Movies with lurid titles like “Spontaneous Combustion” and “The Mangler” hide essays about the history of labor, Cold War iconography, and the corrosive legacy of a culture built on lies. Hooper is still too often represented as a man with a monolithic legacy, the creator of one great film and nothing else. It’s well past time the depth and breadth of his obsessions and his gifts were discussed by a culture that ignored his years of hard work. “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” is literally just the start of one of the most exciting, free, and expressionistic bodies of work in the American cinema.

Poltergeist (1982)

There’s some controversy about the individual contributions to the film made by Mr. Spielberg and Mr. Hooper, best known as director of The Texas Chainsaw [sic] Massacre. I’ve no way of telling who did what, though Poltergeist seems much closer in spirit and sensibility to Mr. Spielberg’s best films than to Mr. Hooper’s. ~Vincent Canby, The New York Times, June 4th, 1982

To the sounds of a slightly gaudy version of “The National Anthem,” the credits fade in and out in the unmistakable Citizen Kane font. Both it and Poltergeist are about the corrupting influence of money and media, and Hooper was about to become the Orson Welles of genre film. Poltergeist is less overly literal than Kane, but it’s no less potent, though there’s a slightly better allegory in Welles’ body of work. In Welles’ 1946 film The Stranger, a perfect suburban family is broken up when they realize that one of them is a Nazi out to steal their daughter. In Poltergeist, a perfect suburban family is broken up when a ghost invades their house and steals their daughter. The connections between Welles and Hooper is everywhere once you notice it. There’s the fact that both were judged their whole career against their iconic first success. Welles’ work with cinematographer Greg Toland seems to define Hooper’s relationship with the camera. Salem’s Lot and The Stranger have the same story beats and New England setting. In 1951, Welles adapted Othello, which is about a man driven to kill by a manipulative puppet-master, not unlike Leatherface and the Carny Mutant from The Funhouse working for their evil father figures. The Trial’s persecuted Josef K and The Funhouse’s Amy Harper both spend the third act fleeing malevolent forces in expressionistic lighting. The decaying family tree of Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons shed leaves all over Hooper’s filmography, most notably in his Texas Chain Saw movies. Texas Chainsaw 2 even has a deranged spin on the Ambersons’ ball, that film’s famous centerpiece.

Poltergeist starts by taking on the neuroses of filmmakers from the ’50s: the emergence of TV. Film after film (All That Heaven Allows, It Should Happen To You, Sunset Boulevard, etc.) feared the small screen would usurp the silver screen, that people wouldn’t leave their houses if they could stare at a hole in a box in the corner of the den. Having made Salem’s Lot for CBS and having grown up in the ’50s when the television first started making its way into American homes, Hooper understood the allure and drawbacks of TV. Poltergeist’s first image is of the blurry lines of a TV screen in extreme close-up. Director of photography Matthew F. Leonetti, playing by the Amblin Entertainment guidebook, lights to pick up maximum dirt and dust, making the TV screen and the living room it’s housed in seem pre-owned in that 1970s fashion (the look was just going out style, resurrected for nostalgia purposes by Douglas Slocombe for the Indiana Jones movies). The national anthem playing while the family dog gives us a view of the house says that this is the new American dream under Ronald Reagan. The TV tucks everyone into bed. Leonetti follows the dog away from its sleeping owner, giving us a survey of Funhouse’s start and endpoints, from the head of the family, Steve (Craig T. Nelson) ensconced in his easy chair like a gargoyle, the light from the TV like the sparks flying from the murder of the mutant and the fortuneteller. The dog finds wife/mother Diane (JoBeth Williams) asleep alone and a bag of potato chips under sleeping daughter #1 Dana (Dominique Dunne), then licks the hand of son Robbie (Oliver Robbins) and daughter #2 Carol Anne (Heather O’Rourke), which rouses her. With his dozens of movie posters and Star Wars toys, Robbie is almost one of Hooper’s archetypal, precocious tykes. But his expertise in all things science fiction is never put to use (which says more about Spielberg’s script than Hooper). Carol Anne walks to the television, drawn by some strange beckoning force, seeing patterns through the static like a junior Max Renn. “Helloooo? What do you look like? Talk louder I can’t hear you.” As she yells at the television, Michael Kahn’s edit takes us upstairs where Diane is woken up by Carol Anne’s voice, the sound transition edit is identical to the ones Hooper used in Texas Chain Saw, Eggshells, and The Funhouse, maintaining continuity between the different areas of the set and linking them through character. The whole family comes down to watch her communing with the TV set, unsure what to do or say.

Jerry Goldsmith is doing his best John Williams impression on the score. Carol Anne puts her hands up to the TV set, and then Kahn cuts to the beautiful countryside where the Freeling family lives. It’s a bitter little comment— perfect houses and families are only on TV. Poltergeist will not be Leave it to Beaver. Leonetti’s images make it seem like it might be at first, the picturesque suburban neighborhood looks right out of a sitcom. His depth of field is longer than Hooper had ever experimented with before, shooting real streets instead of sets. It doesn’t feel like Hooper’s framing, but Hooper had never filmed a cozy neighborhood before, let alone for an ironic counterpart. So naturally his grammar would have to expand to take stock of the changes. The image of a guy falling off a bike is straight up Spielberg, but the framing of the house and the crane shot that introduces us to the image are plainly Hooper’s work. The imperfections pile up like a traffic accident; the living room, with its hideous brown carpet and tacky furniture, is full of screaming football fans, friends of Steve’s. There’s a skirmish with a neighbor over a shared television signal, the two men using remotes like dueling pistols. Tweety, Carol Anne’s pet bird, has died. Its shadow as it descends into the toilet is straight out of a Looney Tunes short (Dana munches on celery like Bugs Bunny when we see her next and the family share a last name with Isadore “Friz” Freleng, one of Warner Bros. top animation directors). The bathroom is even color-coordinated to match those of the dead bird. Carol Anne wants a proper burial for the bird, complete with cigar box casket and a flower for the dear departed. The dog starts digging up the bird’s grave the minute he’s been laid to rest, a morbid gag of a piece with the window washer from Chain Saw.

As Diane puts the family down for the night, Steve watches A Guy Named Joe on TV (another film about the supernatural which Spielberg would remake as Always in 1989) and rolls a joint for himself and Diane (suddenly, they seem like they could have been the couple who got married in the park at the end of Eggshells). The lighting in the bedroom feels very Hooper, all the lamps on to wash out the focus and make the scene a mix of mundane and romantic. Nelson’s pothead baby boomer reads Reagan The Man, The President, all traces of his former lifestyle hidden from his children. The camera swivels around the bed while Diane tells a story about the police from her youth to which Steve barely listens—a slow dolly right out of Chain Saw. Steve stands up to demonstrate proper diving technique to assuage his wife’s fear of their children falling into the new, planned swimming pool. The lighting is bare and awkward on him in the low angle from the bed, like the lights in Leatherface’s house or the Sawyer home in Salem’s. Steve’s big glasses and dorky nice guy routine say he could be The Funhouse’s Rich all grown up (and not axed to death). The lighting is far uglier than anything in Jaws, 1941, or Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Meanwhile, Robbie and Carol Anne (still adjusting to this new house) are terrified of everything in their room: the trees out the window, the goldfish, the spooky clown doll on the chair across from Robbie’s bed (he looks like a refuge from The Funhouse). Everything looks like scary when lightning strikes. Poltergeist plays rough with the Freeling children. They’re already scared of everything, so having all the normal objects in their room turn against them just confirms all their worst fears about life. Hooper does a spectacular job of maintaining an even hand on everyone’s perspective. No one is our POV character in the way that we’re privy to Roy Scheider, Dennis Weaver, or Richard Dreyfuss’ development in earlier Spielberg films. The character development in Poltergeist is communal, as in Eggshells and Chain Saw. We get a sense of the realistic behavior of each member of the Freeling family without ever being situated behind their eyes. When Carol Anne loses the parakeet, we get little sense during the scene that Hooper feels that this moment (a girl saying goodbye to a beloved pet) is a lynchpin in understanding her experience throughout the rest of the film. It’s Diane’s guilt at having botched the fish’s funeral that gets the most attention, not Carol Anne’s loss. No one experiences anything in the first act of Poltergeist that brings us exclusively to their point of view.

Hooper shoots the family in wides for the most part, favoring dollies to capture the ambling motion of the family unit through their day. Compare this to the shot-reverse-shot family scenes in early Spielberg, which serve to underline our lead’s subjective experience of their family unit, and Hooper’s design begins to stand out. Roy Neary’s family watch him craft his mashed potato landing site from the alienating distance of a separate shot. They’re outsiders to his journey. Here everyone is captured in the frame together. If someone is in the cutaway, it’s typically for a joke, as in the parakeet flushing or Robbie in the tree during the bird’s funeral. We’re at a healthy remove from individuals because the story is the haunting of a family, just as Texas Chain Saw isn’t really Sally Hardesty’s story. It’s the story of two groups of people whose fundamental beliefs place them at odds. Poltergeist is about a family recognizing that the evidence of their “happy” life is as much a threat to their happiness as the demon in their house. They were blinded by the swimming pool, the nice house, and the Reaganomic milestones of their wealth and success as people instead of paying more careful attention to each other. There’s a lot of Spielberg in that scenario, but Hooper’s films until this point in his career all say roughly the same thing and with more focus and aggression. Money, wealth, power, and position are all lies. Happiness is intangible and will not be bought or acquired. The real joy of the film is in the way Hooper plays with the space of the house. After tucking Robbie into bed, Steve says goodnight to him and Carol Anne. Then, in the same shot, he walks down the hall to check in on Dana, who hides the phone she’s not supposed to still be on, but not fast enough. He opens the door again and tells her to hang up. It’s a Spielberg style moment (redolent of the handwriting joke early in Jaws), but executed with Hooper’s lighter touch with the camera and choreography. Steve’s pep talk about the scary tree in the yard, like his phone talk with Dana, isn’t particularly effective and, in a hilarious edit, the kids are suddenly sleeping beside their parents. The tree’s spookiness has won over reason—the first of fear’s many victories over the Freelings. Carol Anne is roused by the TV (the national anthem appears again, heralding the static that comes with the shutting down of the signal for the night—something viewers under 35 will have to have explained to them) and welcomes a cartoonish hand made of smoke from out of the television signal and into the walls of the Freelings’ home, which causes earthquake like tremors in the house. “They’re here!” coos Carol Anne The cut to the caterpillar digging equipment in the backyard is another not-so-subtle clue that the villain will wind up being the real estate company Steve works for. Also unsubtle—Carol Anne switches off pun-loving critic Gene Shalit in the next scene so she can watch static and communicate with “the TV people”.

…

The trouble started when, according to a Los Angeles Times story at the time, advertising for Poltergeist featured Steven Spielberg’s producer credit more prominently than Hooper’s director credit and the Director’s Guild of America sued the production. The lawsuit began an obsession with figuring out who was in control. In that story, as well as in interviews in Ain’t It Cool News, at screenings, the Blumhouse Productions website, the Post Mortem podcast, and Rue Morgue magazine, dissenting takes on the role of Hooper and Spielberg have been collected through the years. Director Mick Garris, who was a publicist for the film, says Hooper was the driving creative force on set. Zelda Rubinstein and camera assistant John R. Leonetti said Spielberg. James Karen said he felt differently, that Hooper was his director. Spielberg published a letter to Hooper in The Hollywood Reporter that read: Regrettably, some of the press has misunderstood the rather unique, creative relationship which you and I shared throughout the making of Poltergeist. I enjoyed your openness in allowing me, as a writer and a producer, a wide berth for creative involvement, just as I know you were happy with the freedom you had to direct Poltergeist so wonderfully. Through the screenplay you accepted a vision of this very intense movie from the start, and as the director, you delivered the goods. You performed responsibly and professionally throughout, and I wish you great success on your next project.

Successful collaboration just isn’t as fun a story as a secret feud. As I was writing this chapter, I was talking to a cinephile friend who expressed surprise that Hooper directed it. Everyone forgets or no one knows. That’s how much history has closed the book on Poltergeist’s director. Feels like Spielberg, must be Spielberg. For what it’s worth, Hooper and Spielberg buried the hatchet—Hooper directed episodes of two different shows twenty years apart (Amazing Stories and Taken) produced by Spielberg, which doesn’t sound like the kind of thing you do through gritted teeth. Whatever else is true of Poltergeist, it sent both Spielberg and Hooper on different, definitive paths. Hooper would become an independent, working for studios that would leave him to his own devices or for TV productions orchestrated by friends like John Carpenter and Mick Garris. Spielberg would try to produce more horror films for up and comers like Joe Dante without ever getting caught up in production debacles like this ever again. Hooper’s choice left him without a mainstream ally to keep him in the public’s good graces. Poltergeist grossed over a hundred million dollars internationally on a ten million dollar budget. The combined gross of the following nine films by Hooper that played in movie theatres wouldn’t amount to half of that. The success of the film would not rub off on him in any way. He wasn’t involved in any way in the production of the film’s two sequels. To make things even more unbearably tragic, by the end of the ’80s, stars Heather O’Rourke and Dominique Dunne had both died appallingly young. There was little silver lining in the making of Poltergeist, but as a testament to the talents of its director and dearly missed stars, it’s invaluable