If history is written by the winners, it’s no wonder the men who took over Hollywood in the late 1910s and 20s wrote out many of the women who helped forge the industry. Pioneers, dozens of them and likely many more names yet to be discovered, have been lost to time as men’s names have been repeated over theirs in film history books. Yet as recently as 1920, director Ida May Park wrote that “women will find no higher calling” than filmmaking in a book about careers for women. According to curator Shelley Stamp, by the next edition of “Careers for Women,” the directing chapter had been excised as women had all but disappeared from behind cameras.

Yet, there was a time in the last century where a woman ran her own studio, as Alice Guy Blaché did when she began her Solax Film Company in Fort Lee, New Jersey. On the West Coast, Lois Weber reigned as one of the top-earning directors of the 1910s. And in that time, Universal Studios once promoted the strength of their women-led workforce. One historian estimated that the scrappy studio north of Hollywood released some 170 movies from women directors from 1914-1919. For comparison, between 2007-2017, only 53 women directed a major studio release that cracked the list of top 100 movies at the box office.

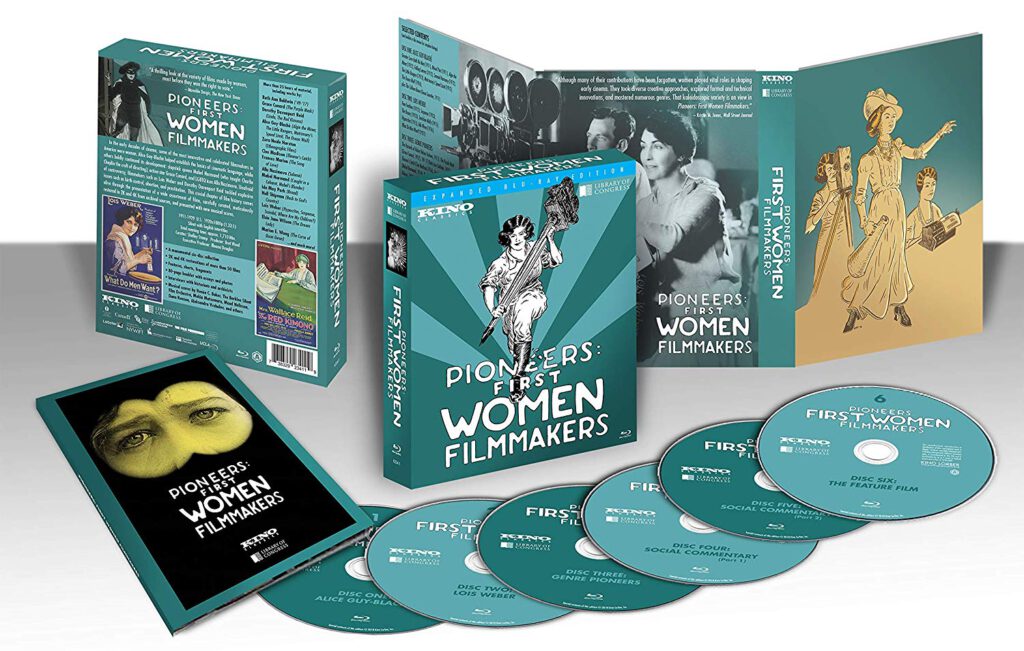

In an effort to surface women’s contributions to early cinema, Kino Lorber released its newest historical box set “Pioneers: First Women Filmmakers” as an expansive six-disc set featuring never before released films, fragments, gorgeous restorations and concise documentaries to help explain the story behind several filmmakers. Certain features and shorts even come with commentary tracks to explain some of the techniques of the day or explore the symbolism and imagery within the frame. Kino Lorber first drew attention to another side of a nearly forgotten chapter in film history when it released the Pioneers of African American Cinema box set back in 2015.

The collection is perhaps one of the most expansive looks at women’s work in early film history. Heavy hitters like Alice Guy Blaché and Lois Weber each have their own disc brimming with titles most audiences— even silent film aficionados—may have never seen before. Among the shorts in the Guy Blaché collection is a comedy about swapping a baby with a puppy called (“Mixed Pets”), a melodrama about the self-sacrifice of a man for the woman he loves in (“Greater Love Hath No Man”), a comedy about gender norms in the west (“Algie the Miner”), and a touching drama about a little girl who tries to save her sister from dying of tuberculosis by keeping the leaves from falling off the tree as the doctor predicted her sibling would die when the last leaf falls (“Falling Leaves”). The collection also features “A Fool and his Money,” Guy Blaché’s 1912 short that was also one of the earliest films with an all-black cast.

These ancient works may be damaged by water or decay, but their ability to awe audiences remains intact. I could feel my skin crawl when watching Lois Weber’s “Suspense,” a stylish thriller that was as effective if not more than D.W. Griffith’s shorts about women in peril. Before Weber was a filmmaker, she worked as a missionary and her imagery in the feature “Hypocrites” is an impressive look at morality in the church. The fragment that remains of “What Do Men Want?” explores the cost of men’s lust for money and sex and the unhappiness of women left in their wake.

The “Pioneers” box set takes a holistic approach to film history, unsavoriness included, as is the case with Universal Studio’s top 1916 hit, Lois Weber’s “Where Are My Children?” Although the film is a provocative drama about abortion and a women’s right to choose, “Where Are My Children?” is on the side of eugenics, a reflection of the popular sentiment at the time that birth control should be used as a means of population control and crime reduction. Though alarming today, it’s still worth watching as a testament to the style of drama and storytelling of the era and as a way to look at how far society has progressed (or not!) over a century.

Over the next four discs, we see women as action heroes in the serials “The Hazards of Helen” and “The Purple Mask” and as the heroine of a western in “‘49-’17.” We laugh at the antics of Mabel Normand, who taught Charlie Chaplin a thing or two about film comedy when the pair worked for Mack Sennett. And we watch with awe as Zora Neale Hurston captures close-up details of the period and of children’s schoolyard games in her ethnographic documentaries of black families in Florida. Extra details on the short “When Little Lindy Sang” tells us that this film about a black girl in an all-white school who saves her classmates from a fire was one of the titles rescued from the abandoned pit of nitrate reels featured in “Dawson City: Frozen Time.” It’s the only known nitrate print in existence that shows the crisp details in close-ups lost in subsequent copies. You’ll also find the unreleased film “The Curse of Quon Gwon: When the Far East Mingles with the West,” a feature Marion E. Wong made with members of her family in Oakland that is believed to be the first film made by and starring Chinese-Americans.

There are many rescued stories like these in the box set’s booklet, which features an introduction by Illeana Douglas, essays by Stamp, a piece by Arthur Dong on the discovery of “The Curse of Quon Gwon,” Charles “Buckey” Grimm on the industrious Angela Murray Gibson who made films in North Dakota, a piece on the history of the Women’s Film Preservation Fund, and a reading list for the budding scholar. At the end of each fragment, short, or feature is a musical credit, and for the first time that I can remember since falling in love with silent film as a high schooler, the women composers outnumbered the men.

We’ll never know the generations of stories and movies that were never committed to film because of discrimination. Some of these surviving gems exist only in fragments or fuzzy copies—if they exist at all. Acknowledging women’s contributions to film history is not a mere feminist gesture. It’s a move towards accuracy, a step toward a balanced view of cinema that doesn’t write out the contributions of women and people of color. I toast the efforts of the archivists, curators, and historians for rescuing our past to build up our present understanding that a woman’s place around the camera is wherever she pleases.