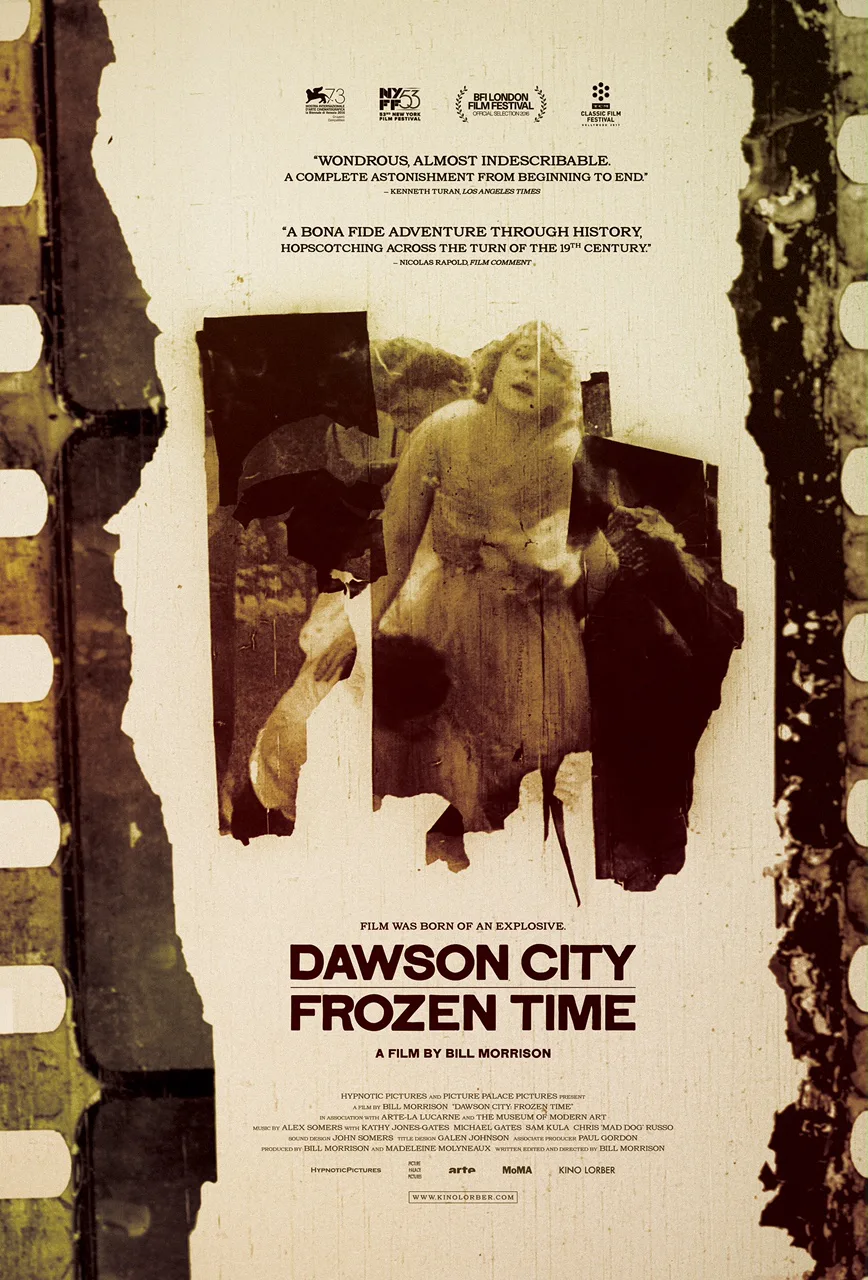

“Dawson City: Frozen Time” is a rather clunky and uninspiring title for a film that’s both revelatory and deeply fascinating. A more evocatively poetic title, say “Gold and Silver,” might suggest the extraordinary double helix of North American history and movie lore that Bill Morrison’s found-footage documentary contains.

The film owes its existence, first of all, to the coincidence that the last half-decade of the 19th century saw both the invention of cinema and a gold rush in a slice of western Canada that previously had been inhabited by Native Americans. In a very short time, hordes of prospectors flooded in, creating Dawson City, a Wild West mining town that reached its peak population of 40,000 within months.

Along with saloons and brothels, the burg’s entertainment options soon included the novel diversion of movies. Within a couple of decades, as the silent cinema reached its artistic peak, the town found itself at the end of a distribution chain for film companies. A movie would open in big cities, then circulate to smaller and more distant towns, before ending up, usually after two years, at farflung Dawson City. Because the distributors didn’t want the prints back, it was up to people in the town to dispose of them.

Some were thrown into the Yukon River. Some were burned: a hazardous undertaking, since the films’ silver nitrate content made them highly combustible. Other films, though, met the unusual fate of being used to fill in a municipal swimming pool that was being paved over to make an ice-skating rink. And it was there, during a construction project in 1978, that hundreds of them were discovered and returned to the world, creating the mother lode of celluloid images known as the Dawson City Collection.

What Morrison has done with this trove of films—as well as many pristine still photographs, some taken by photographers who plied their trade among the original miners—is to intertwine several rich and engrossing narratives: the story of the original Klondike Gold Rush followed by the ups and downs of Dawson City over subsequent decades; the story of cinema as it evolved from a basic recording technology to the highly developed entertainment medium it was by the 1920s (and leaping forward to tell the preservation story of the Dawson City Collection); and the story of the world reflected in the movies uncovered in Dawson City, both newsreels and fiction films.

The gold rush story alone is worth the price of admission. With their combination of greed, foolishness, courage, riches, tragedy and spectacular landscapes, gold rushes are inherently visual and dramatic. The big one in California, though, happened a half-century too early to make it into the movies. The Dawson City boom happened right in sync with the new medium, so that we get to see the steam ships from San Francisco and Seattle and the avid faces of the would-be millionaires they deposit on the banks of the Yukon River, most of them headed only for disappointment as the good claims were staked before the vast majority arrived.

“Mining the miners” was how many folks learned how to make a living in such circumstances, and we get to see an improvised jumble of hotels, boarding houses, gin joints, gambling halls, theaters and various businesses that almost overnight became Dawson City. And then faded almost as rapidly. Finding no gold available to them, and hearing of a new strike in Nome, most miners quickly headed north to Alaska—an exodus appropriately evoked with scenes from Chaplin’s “The Gold Rush.”

The Dawson City they left behind at one point saw its population dip as low as 1,000, but it remained a vital place with institutions such as one that housed both a movie theater and that swimming-pool-cum-skating-rink where the Dawson City Collection would be discovered. The town’s gold mining business, meanwhile, served as a parable of capitalism: the various mines were soon bought up by one company, a tale in which Daniel and Solomon Guggenheim played a key role. During the same span of decades, the array of eventual luminaries who also passed through the area included Jack London, Sid Grauman, Alexander Pantages and William Desmond Taylor.

The American history we see in the films the Dawson City residents would have watched includes such events as the 1914 Ludlow Massacre, in which miners striking a Rockefeller company were gunned down by Colorado National Guardsmen, provoking massive labor protests in the East. Morrison links these events to one of America’s great sports scandals, the World Series of 1919 (the Dawson City Collection includes crucial footage of its games), via the figure of Kenesaw Mountain Landis, an anti-labor judge who helped the government and big business deport radicals and battle labor organizing and was rewarded by being made commissioner of baseball following the scandal. I found these parts of the film to be its most compelling sections, but they almost suggest a much larger work: a Ken Burns history of organized labor and the forces that fought it.

The film contains no narration. Its various stories are told via images and printed titles. Much of its second hour is given over to contemplating many of the entertainment films discovered in Dawson City. These include no lost masterpieces or works by celebrated directors such as Griffith, von Stroheim, Ford or Hitchcock. Rather, what we see is a cavalcade of typical melodramas, adventures, comedies, westerns and romantic tales, mostly from the 1910s. While some of these have aesthetic or social interest, the section containing them feels diffuse and overlong. But that’s a relatively forgivable flaw in a film that offers such an abundance of celluloid and historical riches.