Last week brought news that the 2015 edition of Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide would be its last.

The Guide was a comprehensive paperback listing feature films in alphabetical order. The first edition of Maltin’s book was published 45 years ago, and then titled Leonard Maltin’s TV Movies. It became an indispensable resource for movie buffs, moviemakers, critics and teachers, but also for people who needed to settle bets in bars. As the Internet became more accessible and commonplace, and as the world of publishing changed, it became more expensive to publish this guide. That is our loss. Leonard and his staff of contributors—who wrote reviews of new movies individually yet somehow managed to reflect their boss’s sensibility—made sure that every title and crew credit and actor’s name was spelled correctly and that every notable release date and awards citation was accurate. It was an old-school reference book, published by people with standards.

As Maltin—who blogs for IndieWire in addition to his duties as a critic, film historian, teacher and TV host—put it, the annual paperback was “curated information… It takes time, effort, and a certain degree of expertise to assemble; it’s what sets our Guide apart from the mass of data anyone can find online, for free. But one can’t fight change and I certainly can’t complain about our extraordinary long-term success.”

We asked RogerEbert.com contributors to talk about their own experiences with Leonard Maltin and his Guide (and also interviewed Leonard in this interview by Donald Liebenson). A selection of their comments is included below—arranged, as Maltin would have it, alphabetically, by the authors’ last names. We’ve also embedded a few videos to give a sense of how ubiquitous Maltin was, and still is.

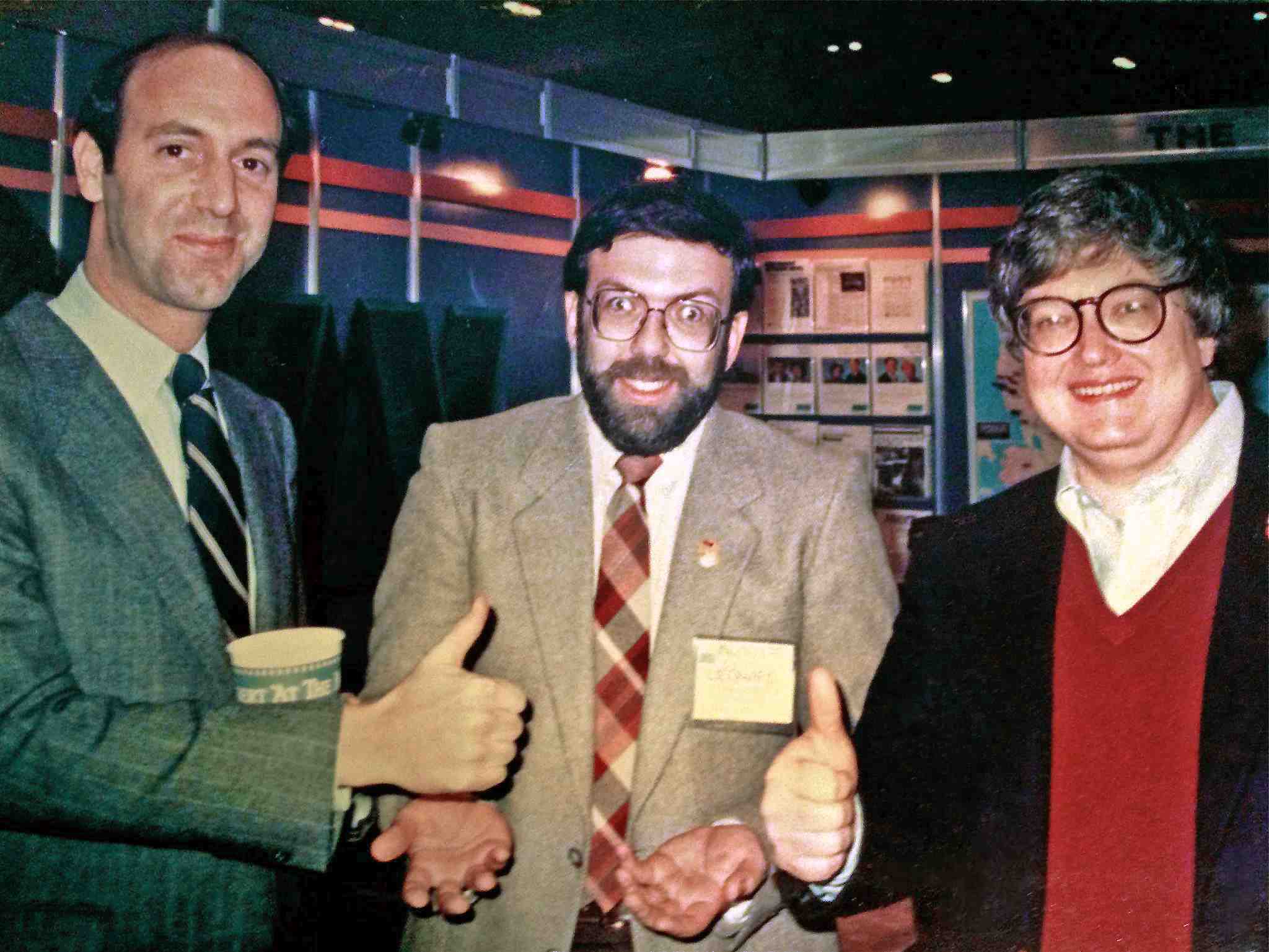

And on a personal note, for many years people asked me and Roger whether there was ever any competition between the Eberts and the Maltins. The answer is an emphatic, “No.” We were always good friends and remain so today. Actually the word “friend” vastly understates our relationship. Leonard, his wife Alice and their daughter Jessie were like family to me and Roger. In fact, some people thought Leonard was Roger’s younger brother. I am happy to see that Leonard will continue his myriad of duties in the world of film and reviewing, and I will cherish the last edition of his Guide, as I have cherished my copies of his previous editions. —Chaz Ebert

I began writing film criticism professionally in 1978.

Recently at my parents’ house in Raleigh, I ran across a review I wrote in the

early ‘80s that for once was not about a movie but about two film books:

Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide and David Thomson’s Biographical Dictionary of

Film (then still in its first edition, as I recall).

They are very different sorts of books but I gave them

equally enthusiastic reviews, saying that I found them as indispensable as

Andrew Sarris’ The American Cinema: Directors and Directions, 1929-1968.

All three books are by critics and therefore opinionated,

yet their value to me lies mainly in their comprehensiveness in covering

certain territory, be it directors or films. Maltin’s book offered elegantly

concise descriptions of every film you might ever want to see. I might have

disagreed with certain emphases or number of stars awarded, yet overall I still

marvel at how solid the judgments his team of writers offered strike me.

It’s a book I’ve never stopped recommending to people, and

the thought that henceforth there’ll be no new edition appearing annually in

bookstores is dismaying. With its disappearance, a certain era of film culture

passes over the horizon.

After that review appeared, I discovered that Maltin and I

had a friend in common who sent him the piece. He wrote me a kind note of

thanks, in a tone as genial as I found the man himself to be when I met him

many years later at the Telluride Film Festival.

Seongyong Cho

When I saw Leonard Maltin for the first time, I did not know anything about him at that point. He briefly appeared in “Gremlins 2: The New Batch”(1990), and the scene in which he was attacked by a bunch of gremlins was one of the funnies moments in the film, but I just thought he was a mere actor playing a fictional movie critic. Thanks to IMDB, I encountered his movie guide around 1998, and I came to know a little more about him and his career as reading many of his capsule reviews. I bought its 2003 edition after his movie guide was no longer available at IMDB, and I have considered buying the new edition since I threw away the 2006 edition several years ago.

Although I have disagreed to his opinions more frequently than before, Maltin’s movie guide has been one of the important parts in my life with movies like Roger Ebert’s reviews, and it is a bit sad to hear that there will be no new edition after this year. This does not exactly feel like the end of an era because he is still active at present, but it certainly feels like the closing chapter for me and other movie audiences who used to look for his short but valuable opinions in his movie guide book.

Matt Fagerholm

In this age of “more is more” online commentary, Leonard Maltin’s work is refreshingly succinct. He could summarize his thoughts on everything from ageless classics to modern hits in just a few sentences. His Movie Guides were my introduction to film criticism when I was a little boy obsessed with Disney films.

The first of his capsule reviews I remember reading was his four-star write-up on Robert Stevenson’s 1964 masterpiece, “Mary Poppins.” He listed every key member of the ensemble and made special mention of the various Oscar-winning artists behind the scenes. Maltin’s encyclopedic knowledge inspired you to search deeper into the archives. He was IMDb.com in print. When he pointed out that Jane Darwell gave her final performance as the bird lady in “Poppins,” I was enticed to learn all about the actress’s extraordinary career, and found out that she won the Best Supporting Actress Oscar in 1941 for her portrayal of the indomitable Ma Joad in John Ford’s “The Grapes of Wrath.” I especially loved how he ended the review with the simple, authoritative line, “A wonderful movie.”

You nailed it, Mr. Maltin. You always did.

I haven’t been in touch with him regularly for a long time,

but for a long time I’ve thought of Leonard as a friend, and a good one.

I was

introduced to him in the mid-80s either by the late, great Roy Hemming, the

reviews editor of Video Review magazine, or by Ed Hulse, another Video Review

stalwart who had known Leonard longer than anybody, by dint of having been part

of the loose network of New Jersey-based film nuts and collectors Leonard had

risen up in, by way of the fanzines he started as a teen.

Through Ed I had also

met film scholars like Richard Bann and animation expert Jerry Beck; these guys

were all part of the same gang, as it were, and I was always awed by their

knowledge and enthusiasm. Leonard, in this group, was the guy who’d made good.

We didn’t call ourselves film nerds or film geeks back in the day. Our derisive

term for the obsessives who used to flood Video Review’s switchboard with odd

questions concerning hardware or why Film X wasn’t yet available on home video

was “drooler,” a category from which we did not entirely exempt ourselves.

In

any event, having established a brand with his Guide and having been so widely

published and then landing a cherry gig at “Entertainment Tonight,” Leonard was

Our Man In The Big Time, and on the not-frequent occasions he was in NYC to

visit Video Review’s offices he never high-hatted anyone the way certain other

well-known contributors were known to do. Like William K. Everson, who was something of a

mentor to all of us, Leonard was just passionate about movies, particularly old

ones, and he was naturally friendly, and naturally more friendly than average

to people who shared his passion.

In the mid-80s his publisher decided to expand his brand

with a film encyclopedia, and Leonard gave Ed Hulse the managing editor

position, and Ed in turn enlisted me and a few other Video Review colleagues to

contribute entries. I got a lot of the esoteric and/or difficult guys—Godard

and such. I had a lot of fun with the assignments; it was an interesting

challenge to take directors of that ilk and translate their appeal/importance

into a critical dialect that was aimed at mainstream tastes.

Not that Leonard

himself always hewed to any kind of critical conventional wisdom. While

conscientious about staying current, his heart is always with old Hollywood,

and his impatience with certain strains of filmmaking is actually very evident

in his movie guides over the years, no matter the myriad of contributors he had

pitching in. I only know the story third-hand, so I can’t really relate it

accurately, but there’s a whole saga in how Leonard was eventually persuaded to

upgrade “Raging Bull,” which I think he had originally given a one-star rating,

to two stars, and how two stars was as high as he’d go. I disagree with

Leonard’s assessment, of course, but I also admire him sticking to his guns.

While the Encyclopedia only yielded one edition—I blame

myself—Leonard’s movie guide remained a constant in all our lives for many

years, and I remember when a box of them would arrive in Video Review’s office

and a bunch of us would tear through the new editions, looking for a quirky

view of a recent release. One thing people tend to downplay because of the

amiable, accessible style of the prose in Leonard’s books—while other writers

contributed a lot, Leonard was meticulous in overseeing the overall tone of the

Guides—is the genuine, consistent, idiosyncratic sensibility on display, as

individual as Leslie Halliwell’s or David Thomson’s, but extremely American,

because Leonard really is an all-American boy, and an all-American success

story.

I will be honest and say I’ve missed a few editions of the

Guide in recent years. And as I mentioned, I haven’t seen Leonard in some time.

But I am confident that when next I see him, he’ll greet me with his customary

warm and sincere smile, and we’ll catch up, and the conversation will be a

pleasure, especially once we get around to talking movies.

Nell Minow

For many years, I kept Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide on my desk at work. The ostensible reason was an open bet with anyone who came in to see me — they could pick a page number at random and if I had not seen a movie on that page, I had to buy lunch. I’m glad to say I never lost.

But the real reason was that I liked seeing it there to remind me of all the movies I loved and all those I had yet to see. I liked having it there to refer to if, in the middle of working on something completely unrelated, I felt the impulse to check some movie’s director or year of release. Maltin’s book was not just astonishingly comprehensive. Those haiku-like little capsules were remarkably insightful, models of how to convey the essence of a film in the context of its aspirations and its contributions. I wrote a fan letter to Mr. Maltin once, using the excuse of a minor correction to tell him how much his books, including the movie guide, meant to me. I got back a beautiful response, on extremely cool Mickey Mouse stationery. He is a true scholar and a gentleman. I have ordered the 2015 edition for myself and one for my parents, who love to consult it for their Netflix queue. It will remain a treasured resource for us both.

Lisa Nesselson

At my house (one film critic + one film historian) for decades we have been known to fall into what we call “a Maltin coma.” You go to look up one movie and—like thumbing through the dog-eared card catalogs of old—you just keep going, carried away on a small, pleasurable wave of serendipity.

Analog. The “links” are ink on paper, not links in cyberspace.

We might need a duel at dawn to settle this, but I remain convinced that it is faster to just reach for “Maltin” than to do a web search.

Plus, consulting a Leonard Maltin Movie Guide does not contribute to global warming. You do not need to plug it in. Not having ads blink at you is nice. Nobody can hack into your page-turning. The NSA does not know whether you consulted the entry for “Portrait of a Hitman” or “The Portrait of a Lady,” “The Terrorists” (1975 with Sean Connery, pictured above) or “TerrorVision.”

Consulting Maltin keeps your brain on friendly terms with alphabetical order. It is a marvel of concision of the fact-checked variety.

On page 696 (out of 1648!) of the 2001 edition currently at my feet, one may read the review of 1948’s “Isn’t It Romantic?” The review, in its entirety reads as follows: “No.”

This got Maltin into The Guinness Book of World Records for having written the shortest film review ever.

At the French-American Film Workshop in Avignon in 1992 my husband and I were waiting in line with Quentin Tarantino to get in to see Paul Mazursky’s version of “The Tempest.” “It says in your bio that you appeared in Godard’s 1987 ‘King Lear’ but I can’t figure out which part you played,” I asked the affable writer/director.

He laughed (like a hyena crossed with a machine gun, if memory serves) and said, “Yeah, well, when you’re starting out and you don’t have many credits, you pad your resume. I figured if anybody asked, I could say I was one of those three guys in the distance in one scene.”

Maltin’s guide fell for it (afterall, it was in the bio note in the press kit for “Reservoir Dogs” which is where I’d seen it) and ran Quentin as part of the (already sufficiently surreal) cast for several editions.

In the journalism racket we call asking the person in question “a primary source.” So many smart concientious people have built the Maltin Guide over the years that I consider it to be every bit as good as a primary source. Yes, in addition to facts (if they say it’s in Panavision it probably is) each tome offers opinions — but I find they’ve rarely steered me wrong.

Leafing through a Maltin guide is a pleasure along the lines of browsing through LPs in a record store or finding a nickel in the coin return slot of a pay phone. As the song goes, “No, no, they can’t take that away from me.”

Michał Oleszczyk

I had no idea who Leonard Maltin was when I picked up the 1997 edition of his guide in an English-language bookstore in Southern Poland, where I grew up. It wasn’t his name that drew me to it, but the Bible-like heftiness of the volume (I never before saw a movie book like it).

It wasn’t a full year after I bought it that my copy broke in half from heavy overuse — it’s fair to say I had been looking up every single movie playing on Polish television (which was all the trickier, for Polish TV listings didn’t give you the English title back then). I loved the one-two-punch brevity of the notes, I loved the fact that widescreen ratio was indicated, and I dreamt of watching every single movie awarded the coveted four-star rating. And boy, what a joy was it to track down fare like “Major Barbara”, “Tunes of Glory” and “Seven Days to Noon” (pictured above).

Last but not least, I kept soaking up new English words and phrases, some of which will never leave me (“a taut actioner” is probably my favorite). Many years later, when I first visited the United States and saw Maltinon TV, I thought to myself: this is the man who gave me the idea of just how many movies are out there. It’s fait to say that his critical judgment didn’t influence me that much (although I swear by his “Disney Movies” volume), but in a strange way he made the boundless universe of film into a friendly place to navigate and explore.

Matt Zoller Seitz

Not many people know this, but until about 1995, I was the Internet Movie Database.

More accurately, in the dark years before the Internet became an easily accessible repository of all knowledge, I served the same function as the Internet Movie Database, via telephone, between the hours of 5 and 7 p.m. on weekdays. That was the window during which happy-hour drinkers would phone the offices of Dallas Observer, where I was employed as a staff writer and film critic from 1991-95, to settle bets about movies.

“What’s the name of that movie…with the guy…who’s wearing…the [expletive] hat?” one might slur into the phone, whereupon I’d elicit as many additional bits of information as I could (character names, actor names, black and white or color) then reach for Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide or some other thick paperback and find the answer.

Most of the people on the other end of the line didn’t seem to know that there was such a thing as a film reference guide, so they were awed by my seemingly limitless knowledge of who played what in which film released in what year. On days when I had heavy deadlines or didn’t feel like adjudicating the disputes of tipplers, I’d let the calls go to voicemail, sit there in my chair, and just read Maltin’s book for pleasure.

Thanks, Leonard, for making me seem smarter than I was.

Peter Sobczynski

These

kids today with their complicated pants and their leaked selfies and their

“Boom Clap” and whatnot. If you try to explain to them that there was

once a time in the not-too-distant past when the pertinent information about

any movie–ranging from obvious stuff like who was in it or its official

running time to more esoteric details like the aspect ratio or the existence of

alternate cuts–was not immediately accessible with a couple of quick keyboard

strokes, they may look at you as if you are insane, a dinosaur or both.

And yet, there was once just such a time and for anyone who bore even the

slightest interest in film history back then, there was. . .well, it would

undergo a couple of name changes over the years, most recently to “Leonard

Maltin’s Movie Guide,” but to most people, it was referred to simply as

“Maltin.” Yes, there were other books out there that collected brief

capsule reviews of films, but the one that that Maltin and his small army of

contributors put together since its inception in 1969 (it would become an

annual concern in 1988) was different. Despite only being allowed a few sentences at most per title (and they would try to include as many films as was possible to fit in without overwhelming the binding), the write-ups

demonstrated a wit and style and sense of the history of cinema that was a

rarity even back then, and which perfectly straddled the line between mass

acceptability and academic rigor.

On the one hand, I would often make a copy of

the current edition (with the must-see films highlighted) part of my gift to

acquaintances tying the knot. On the other, I would keep a copy on hand around

as an invaluable part of my work life and even long after the Internet seemed

to make it less relevant, I would continue to use it as both a primary resource

and as the final arbitrator in any movie-related bets. When I get my copy of

the final edition, I will continue to do so. In fact, I may need to get an

extra copy for when (not if) I wear the first one out from constant use. To my

eyes, it belong on the same shelf of essential reference books as The Oxford English Dictionary, The

Encyclopedia Britannica and Roget’s Thesaurus.

And yet,

there was more to Maltin and his work than just his long-running stewardship

of the guide. I was actually first

exposed to him as a young child with a precociously advanced interest in the

world of film when I would wander to the cinema section of the adult portion of

the Barrington Area Library and repeatedly check out a number of wonderful

books that he had also written, such as “Movie Comedy Teams,”

“The Great Movie Shorts,” “The Disney Films,” “Our

Gang: The Life and Times of the Little Rascals” and “Of Mice and

Magic.”

These were works that conveyed an enormous amount of historical

detail regarding their subjects in a breezy manner that was both edifying and

entertaining to read. (To this day, those volumes hold places of prominence in

my personal library of film-related books.) His encyclopedic knowledge of the

history of Disney animation would also lead to his curation of a well-regarded series of DVD releases of shorts, TV programs and other obscurities from the studio’s vaults. I also

recall him as the film critic during the early days of “Entertainment

Tonight” when he provided a brief respite from the gossip and froth. He was one of the few legitimate film critics who not only knew his stuff but was

able to present it in a telegenic manner.

He even turned up in one of the

more inspired gags in the gleefully anarchic “Gremlins 2: The New

Batch” (see clip above) in which he allowed himself to be savaged—literally—by the

titular creatures for having given a middling review to the original “Gremlins.” It is enough to almost make one forget that Maltin once gave 2 1/2 stars to

“Laserblast.”

Gerardo Valero

Sometime around 1983 I got the chance to watch my first movie review on T.V. when Entertainment Tonight debuted in one of our cable stations here in Mexico. Ironically, that would have been at least a two or three years before the Siskel & Ebert review show even entered the picture for me. What I found most attractive about Mr. Maltin’s reviews back then was trying to outguess my brother the rating that each movie would receive at the end of each segment based on his comments (on a 1 to 10 scale). In 1988 I bought my first of his Movie Guides, a personal tradition that lasted for over 20 years until, as it is with things in life, the printing started to feel a little bit too small (even with reading glasses).

In 1996 I sent Mr. Maltin some comments on the latest edition. Not only did I receive a personal return letter from him (reproduced below), he even gave a full, detailed response to each of my opinions.

During the early years of buying the book I tried to save every prior edition but eventually I found much more satisfying giving them away to eager family and friends. This means that the one constant to be found in the home of most everyone I know is a past edition of Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide.

Susan Wloszczyna

What Roget was to the thesaurus and Webster to dictionaries, Leonard Maltin was to movie guides. Long before the acronym IMDB existed, film fanatics relied on the film historian and critic’s handy paperback movie guide to find a pithy, no-nonsense review of an oldie that happened to pop up on TV or to settle a bet about whether Walter Brennan or Ward Bond was John Wayne’s sidekick in a certain Western. At some point in my youth, the chunky tome became a must-have entertainment bible that took a place of honor right alongside the TV Guide. I remember buying the yearly updated editions as Christmas presents for my Dad, who loved checking the names of character actors from Hollywood’s golden age. Once VCRs made classic titles easily accessible on video, the guide became even more invaluable for hunting down worthy titles.

While many assume that Maltin wrote all those thousands of capsule summaries himself, he had a knowledgeable team of contributors to keep each version current with the latest releases – including my colleague Mike Clark back when we both were film critics at USA Today. I had the pleasure of getting to know Leonard personally over the years, the first time when I interviewed him for the 25th anniversary of the guide. I declared his new collection to be four-star-worthy and was tickled to see my rating on the back of the book’s cover. Over the years, he always made himself available for interviews and we often discussed our mutual baby-boomer-ingrained passion for all things Disney, especially animation. When he began appearing on TV regularly, what you saw was the Leonard you got offscreen. A warm human being and a gentleman, smart but also highly approachable. If Siskel and Ebert were like your bickering smart-aleck cousins as they engaged in dueling opinions, then Leonard Maltin was like the favorite uncle you regularly turned to for advice – and who rarely steered you wrong.