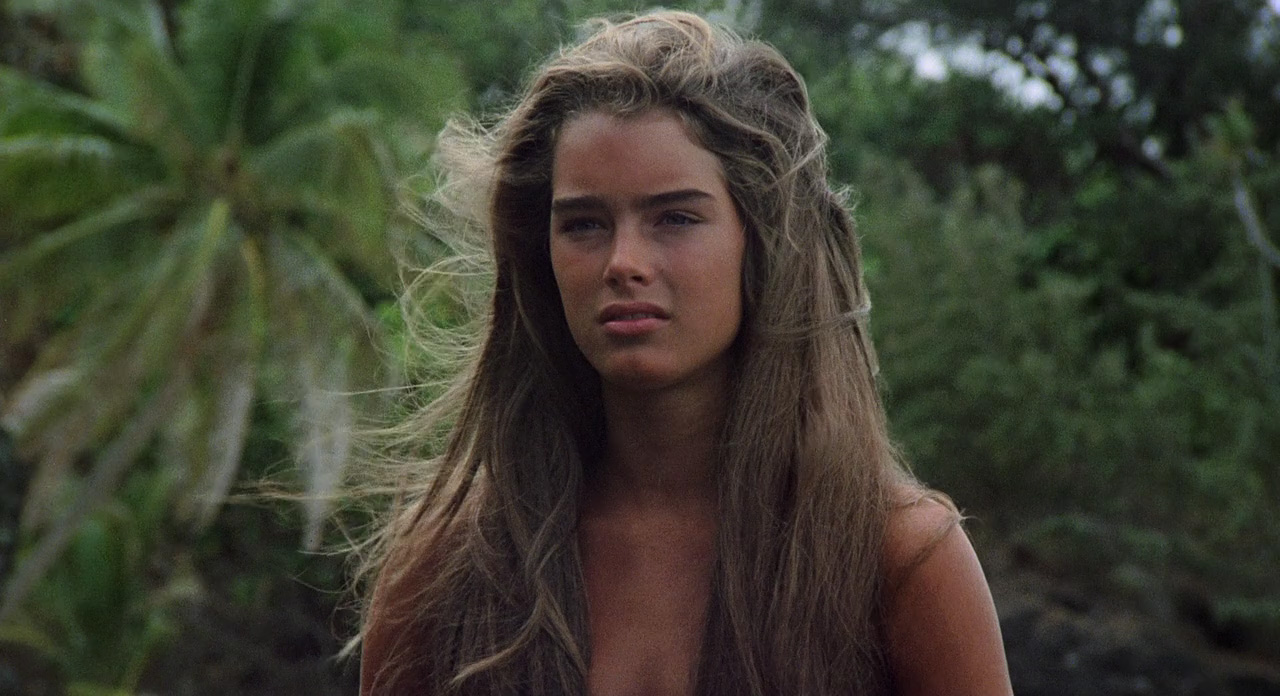

“What are you doing?” It’s a question asked a lot throughout “The Blue Lagoon,” “Grease” director Randal Kleiser’s 1980 adaptation of the early 20th century story of shipwrecked cousins growing up in isolation on an island. The film, which Roger Ebert called “the dumbest movie of the year” was a box office success and critical failure, generating controversy for its sexual content featuring a 14-year-old Brooke Shields. Watching the film today, “what are you doing?” is a resonant thought. The horny, expository melodrama makes for an awkward watch that becomes more interesting when considering the context of its star.

As Emmeline, a teen who knows only island life, Shields is tasked with making an archetypal naïf of a girl convincing. She does a slightly better job than Christopher Atkins, who, as her cousin/lover (gross, but also kind of inevitable) Richard, delivers his lines woodenly. Shields had the dubious achievement of winning the very first Razzie Award for Worst Actress for her role. Her performance may not be great, but to call it the worst of that year is too harsh. And besides, she’s not really playing a role so much as modeling, filling out a whisper-thin part with beauty.

In the ’70s, of course, Shields was famous for being so beautiful and so young. The way the media discussed her verged on fetishistic, and she had already courted controversy with her starring role as a child prostitute in Louis Malle’s “Pretty Baby” (1978), a much better film. Shields’ preternatural prettiness is the guiding force of “The Blue Lagoon,” and while the hair inspiration she provides is impeccable and her smile is luminous, there’s no way to watch some of the film’s more supposedly sensual scenes without cringing.

When it comes to the depiction of burgeoning sexuality, “The Blue Lagoon” wants to have it both ways. Teen horniness is guileless, with puberty making itself known through rather obvious dialogue (“I keep having strange thoughts,” says Emmeline, “Why are all these funny hairs growing on me?” asks Richard, etc.) Sexual discovery is here the natural outcome of the storybook (or, if you’re so inclined “biblical”) situation. So yes, the soft-focus montages of teen flesh are gratuitous but the film presents it all as innocent—these kids don’t even know what sex is! They don’t even know how a baby is made! They learn it the hard way, obviously. By couching sexuality in primitive purity, “The Blue Lagoon” gets away with perversion that would likely be even more controversial today.

Unfortunately, all this sex and subversion of virtue doesn’t add up to a secret feminist masterpiece. “The Blue Lagoon” is lovely to look at (it was shot by Nestor Almendros, who worked with such legendary directors as François Truffaut and Terrence Malick) but suffers from its eye-rolling dialogue and strange softcore-meets-survival-drama tone. And the sexualization of Shields would continue throughout 1980. Just a few months after the release of “The Blue Lagoon,” she appeared in a series of ads for Calvin Klein Jeans, asking in the most notorious of the bunch, “You know what gets between me and my Calvins? Nothing.” Citing concerns that the commercial verged on child pornography, CBS refused to air it, and ABC followed suit.

As a teen star, Shields was presented as a “good girl” whose famously strong brows offset her delicate features. Her public image, even when she was generating controversy, still projected a borderline ridiculous level of naïveté. In a 1982 interview published in Scavullo Women, a book of beauty tips, she was quoted as saying, “I’m totally against all kinds of drugs. Even cigarettes. I get my quote-unquote highs from other things: babies, guitar music, animals”—and this was two years after she starred in this horny teen opus. Was there a wink in this statement, a trace of irony in its saccharine quality? It’s hard to say, and when considering that Shields was paid to be beautiful from her birth (her first brush with stardom came via an Ivory Soap ad as a baby), one can’t help but wonder about her level of self-awareness.

Hollywood is littered with stories of child stardom’s dangers, but even with the questionable sexualizing of her pure loveliness, Shields seemed remarkably well-adjusted. “There’s never been a time when I’ve said I just wanted to be a kid, because all along I have been just a kid,” she said in the same interview. This presentation of real-life innocence makes the onscreen presentation of “The Blue Lagoon”’s innocent/horny mélange feel unsavory. As Emmeline, Shields’ innocence turns into an overripe sexual fantasy. The fact that she doesn’t know exactly what sex is is supposed to make you feel better about watching her have it. Such logic was flimsy enough nearly 40 years ago, and feels even worse today. In her heyday, which just happened to coincide with the tail end of second-wave feminism, Shields seemed both younger and older than she was. “The Blue Lagoon” is nothing if not a cinematic version of Britney Spears’ “I’m Not a Girl, Not Yet a Woman” twenty-some years before the fact.

“The Blue Lagoon” had been adapted twice (in 1923 and 1949) before the 1980 version achieved notoriety and twice since. “Return to the Blue Lagoon” (1991), starring Milla Jovovich, managed to receive even worse reviews than its predecessor, and “Blue Lagoon: The Awakening,” a Lifetime film from 2012, definitely isn’t canon. Perhaps Hollywood’s remake mania will bring another “Blue Lagoon” in the future, but there’s no perfect way to smooth out the sexual politics, and there’s likely to be little to recommend without Shields’ compelling mythology.