This movie made me itch. It’s about a young girl and a young boy who are shipwrecked on a beautiful Pacific Island. It shows how they grow up, mostly at sunset. It follows their progress as they discover sex and smile sweetly at each other, in that order. It concludes with a series of scenes designed to inspire the question: If these two young people had grown up in civilized surroundings, wouldn’t they have had to repeat the fourth grade?

“The Blue Lagoon” is the dumbest movie of the year. It could conceivably have been made interesting, if any serious attempt had been made to explore what might really happen if two 7-year-old kids were shipwrecked on an island. But this isn’t a realistic movie. It’s a wildly idealized romance, in which the kids live in a hut that looks like a Club Med honeymoon cottage, while restless natives commit human sacrifice on the other side of the island. (It is a measure of the filmmakers’ desperation that the kids and the natives never meet one another and the kids leave the island without even one obligatory scene of being tied to a stake.)

Why was this movie made? Presumably because Randal Kleiser, the director and producer, read the 1903 novel it’s based on and vowed that this story had to be brought to the screen. It had been filmed previously, as Jean Simmons’ 1949 movie debut, but no matter. Kleiser had another go.

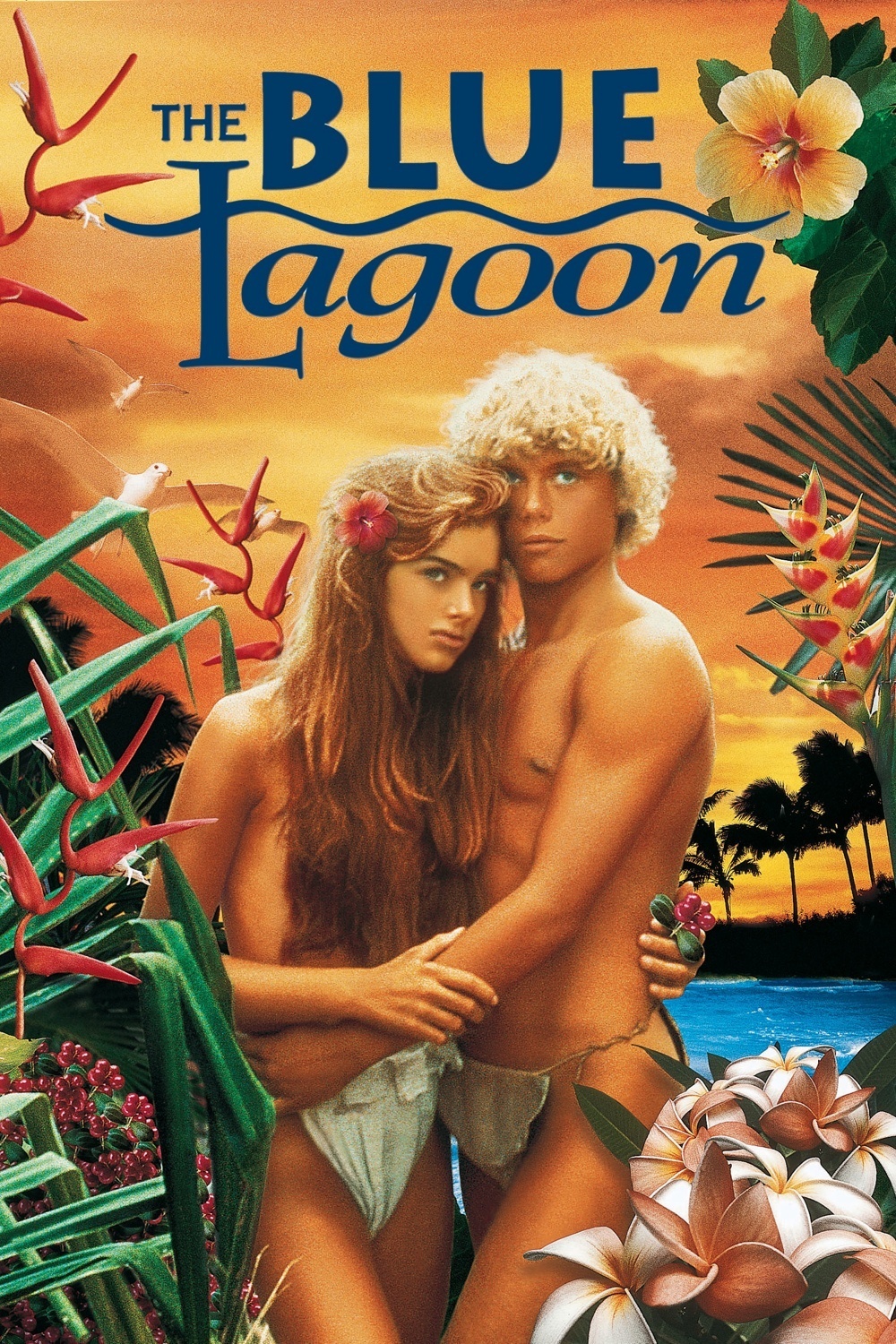

It’s intriguing to try to guess, on the basis of the film he made, what he thought the original story had to tell us. This movie could have been made as a tale of wilderness survival: The Swiss Family Robinson Meets Lord of the Flies. But Kleiser’s details about daily life are wildly unconvincing. This movie could have been made as an adventure epic, but, as I’ve already mentioned, the threat of the natives on the other side of the island is introduced only to be dropped. This movie could have been made as a soft-core sex film, but it’s too restrained: There are so many palms carefully arranged in front of genital areas, and Brooke Shields’ long hair is so carefully draped to conceal her breasts, that there must have been a whole squad of costumers and set decorators on permanent Erogenous Zone Alert.

Let’s face it. Going into this film knowing what we’ve heard about it, we’re anticipating the scenes in which the two kids discover the joys of sex. This is a prurient motive on our part, and we’re maybe a little ashamed of it, but our shame turns to impatience as Kleiser intercuts countless shots of the birds and the bees (every third shot in this movie seems to be showing a parrot’s reaction to something). And there is no way to quite describe my feelings about the scene that takes place the morning after the young couple have finally made love. They go swimming, see two gigantic turtles copulating, and smile sweetly at each other. Based on the available evidence in the movie, they know more at this point about the sex lives of turtles than about their own.

But wait. These kids aren’t finished. They have a baby, after long, puzzled months of trying to figure out those stirring feelings in the girl’s stomach. “Why did you have a baby?” the boy asks. “I don’t know,” the girl says. They try to feed the kid fresh fruit, and then they look on in wonder as the baby demonstrates the theory and practice of breast-feeding (so that’s what they’re for!).

The movie’s ending is enraging. It turns out the boy’s father has been sailing the South Seas for years, looking for the castaways, who meanwhile manage to set themselves adrift at open sea again (they lose their oars … but never mind). Despairing of being rescued, the kids have just eaten berries that are supposed to put them permanently asleep. Then their unconscious bodies are rescued. Will they live? Die? What were those berries, anyway? The movie cops out: The burden of contriving an ending was apparently too much for such a feeble movie to support.