“If you are going to spend your time doing the best you can doing shit, then why do it? If you are going to spend your time giving to future generations some of the benefits of your knowledge, maybe that is a way of having a legacy, that is a way of having a kind of immortality…so that…something is gonna live and that I think is a pretty valuable thing.”—Haskell Wexler in Daniel Raim’s 2010 documentary, “Something’s Gonna Live” (Haskell Wexler was born February 6th, 1922, and passed away on December 27th, 2015.)

Today, February 6th, 2022, would have been the 100th birthday of Oscar-winning cinematographer and filmmaker, Haskell Wexler (“HW”). He was named one of film history’s ten most influential cinematographers in a survey of the members of the International Cinematographers Guild. In September 2016, the George Lucas Family Foundation created the Haskell Wexler Endowed Chair in Documentary at the USC School of Cinematic Arts. “Haskell Wexler wasn’t just one kind of artist, he had many different interests and brought them all to the way he told stories…His singularity was in the way his passion was evident on the screen,” said George Lucas.

HW was also an activist who stood firmly when speaking truth to power on behalf of those who were powerless. Even into his nineties, Haskell fought to shorten the hours of filmmakers who worked long exhausting days and then sometimes fell asleep at the wheel driving back to their hotels. When oral historian Studs Terkel was asked near the end of his life who he felt was still fighting the good fight to make the world a better place, without hesitation, he named Haskell Wexler. Although HW preferred not being the center of attention, he endorsed the work of documentarian Pamela Yates who made a film about him called “Rebel Citizen.”

Haskell was also rather shy. In one of the shortest acceptance speeches at an Academy Awards ceremony HW said when accepting the Oscar for “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?”, “I hope we can use our art for peace and for love.” No one knew him better than his loving wife, actress Rita Taggart Wexler. “Two of the most fundamental things you must know about Haskell are that he was fearless and tenacious,” she told me via e-mail. “He was considered a premature anti-fascist. He was known for his support of anti-lynching laws. He was harassed. Audited annually. He lost his passport. All of this told him he was following the right path. His fearlessness and tenacity only got stronger when he held a camera to his eye.”

Today, we are paying tribute to him by looking back at some of Roger’s most memorable coverage of Haskell, beginning with his interview with him on August 10th, 1969. Haskell had already made a name for himself as the Oscar-winning cinematographer of “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?”, before helming his own breakthrough directorial feature, 1969’s “Medium Cool,” a narrative effort that famously filmed scenes during the violence that erupted during the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, in which a TV reporter (played by Robert Forster) finds himself in over his head. Roger wrote that “Medium Cool” was “the best film ever made in Chicago […] but it is not a ‘Chicago film’ any more than it’s a film about politics, hippies, cops, violence, sex, poverty, black militants or its other subjects. It is a film about the nature of communication, about the shades of meaning that can be superimposed on the face of ‘reality.'”

During their conversation, Haskell argued that, in fact, nothing is “real,” noting, “When you take a camera down to Michigan Avenue and point it at what’s happening, you’re still not showing ‘reality.’ You’re showing that highly seductive area that’s in front of your camera. But there’s another element in the film. It has something to do with the professional, ‘just doing his job.’ The film opens with that shot of the accident on the Outer Drive, and the two TV guys photograph it first and then report it to the police. Their job comes before their involvement. That business of ‘just doing my job’ almost became a joke at the Nuremberg trials. But it’s very much a part of our lives now. There are people with nice suits, air-conditioned offices, grammatical English, who use their education to plan the end of the world, the destruction of people. I mean literally. One of the things we have to deal with, I think, is whether ‘professionalism’ comes before individual social responsibility.”

In Roger’s four-star review of “Medium Cool,” he wrote, “Conventional movie plots telegraph themselves because we know all the basic genres and typical characters. Haskell Wexler’s ‘Medium Cool’ is one of several new movies that knows these things about the movie audience […] Of the group, ‘Medium Cool’ is probably the best. That may be because Wexler, for most of his career, has been a very good cinematographer, and so he’s trained to see a movie in terms of its images, not its dialog and story. […] ‘Medium Cool’ is finally so important, and absorbing because of the way Wexler weaves all these elements together. He has made an almost perfect example of the new movie. Because we are so aware this is a movie, It seems more relevant and real than the smooth fictional surface of, say, ‘Midnight Cowboy.'” “Medium Cool” would later screen at Ebertfest in 2003, followed by a Q&A between Roger and Haskell.

In 2012, Haskell returned to Chicago with director Andy Davis (“The Fugitive“) and Mike Gray (“The Murder of Fred Hampton”) to document protests against the G-8 Summit and NATO. It resulted in his documentary “Four Days In Chicago” (you can read about it here). His other directorial efforts include the first Oscar-winning documentary short, “My Lai Veterans” (1970), “Brazil: A Report on Torture” (1971), “Introduction to the Enemy” (1974), “Target Nicaragua: Inside a Covert War” (1983) and “Bus Riders Union” (1999).

In 2006, he made a documentary that turned a spotlight on the unfair work hours demanded by his industry, “Who Needs Sleep?” “Documentaries are the voice and the conscience of the people,” Wexler told Documentary magazine in 2006. “When I hear someone say they are making a film because someone at a network likes that subject, it leaves me cold. You have to trust your gut instincts and what’s in your heart to tell meaningful stories; that’s what makes it an art.”

Haskell went on to win a second Oscar for lensing “Bound for Glory,” Hal Ashby’s 1977 biopic on Woody Guthrie, starring David Carradine. Roger hailed it as “one of the best-looking films ever made, in its photography, in its use of locations, in its recreation of the America that Woody Guthrie discovered.” In his four-star review, he wrote that there are images in the film “so striking or so beautiful I doubt I’ll ever forget them; this is the most visually accomplished film since ‘Barry Lyndon’. […] One awesome shot shows a dust storm approaching the little town, and another shot is on top of a freight train, held for minutes without a cut, while Woody and a fellow hobo exchange philosophies while the train moves past the endless fields, disappears into the darkness of a tunnel, emerges, seems ready to run forever. Shots like those have rarely, if ever, been handled so well.”

We were pleased to open the 2013 edition of Ebertfest, just weeks following Roger’s passing, with one of his favorite films, Terrence Malick’s 1978 masterpiece, “Days of Heaven.” Haskell was in attendance for a post-screening Q&A moderated by our editor-at-large, Matt Zoller Seitz. (You can watch their full conversation in the video embedded below.) “‘Days of Heaven’ is above all one of the most beautiful films ever made,” wrote Roger in his Great Movies essay on the film. “Malick’s purpose is not to tell a story of melodrama, but one of loss. His tone is elegiac. He evokes the loneliness and beauty of the limitless Texas prairie. […] The credit for cinematography goes to the Cuban Nestor Almendros, who won an Oscar for the film; ‘Days of Heaven’ established him in America, where he went on to great success. Then there is a small credit at the end: ‘Additional photography by Haskell Wexler.’ Wexler, too, is one of the greatest of all cinematographers. That credit has always rankled him, and he once sent me a letter in which he described sitting in a theater with a stopwatch to prove that more than half of the footage was shot by him. The reason he didn’t get top billing is a story of personal and studio politics, but the fact remains that between them these two great cinematographers created a film whose look remains unmistakably in the memory.”

Another film in which Roger greatly admired Haskell’s photography was John Sayles‘ 1994 fantasy, “The Secret of Roan Inish,” about a young girl, Fiona (Jeni Courtney), who uncovers the mysteries in her grandparents’ fishing village. The film’s secret, according to Roger in his review, “is that it tells of this young girl with perfect seriousness. This is not a children’s movie, not a fantasy, not cute, not fanciful. It is the exhilarating account of the way Fiona rediscovers her family’s history and reclaims their island. […] John Sayles and Haskell Wexler, who has photographed this movie with great beauty and precision, have ennobled the material. There is a scene where a person numbed by the cold sea is warmed between two cows, and we feel close to the earth, and protected.”

Haskell won an Independent Spirit Award for his cinematography in John Sayles’ film “Matewan,” for which he was also nominated for an Academy Award. His cinematography was also nominated for Academy Awards in 1975 (“One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest”) and in 1989 (“Blaze”). When he filmed Sidney Poitier in 1967’s “In The Heat of the Night”, he became one of the first cinematographers on a major Hollywood movie to intentionally adjust the lighting to be more appropriate for Black skin.

Haskell was revered as much for his social activism as he was for his film work, and was a tireless advocate for those who had no voice. He called the 2014 death of Sarah Jones, a 27-year-old assistant camera operator on “Midnight Rider,” criminal negligence. One of his last big advocacy pushes was to warn the powers that be against going to war. Yet he was a war hero who survived two weeks in a lifeboat after his Merchant marine supply ship was torpedoed by a German U-boat in the Indian Ocean on November 13th, 1942. His wife Rita attributes his lifelong fight for justice and world peace to this experience. She said, “It gave him a sense of urgency to get things done. He still lives with this awareness of the fragility of life and the obligation one has to honor others.” As a Pacifist he never tired of advocating for peace.

On his 100th birthday, we also send regards to his family: His widow, Rita Taggart; His children– Katherine Wexler Schmidt, and award winning sound man Jeffrey Wexler (wife Carol); and filmmaker Mark Wexler (who made a film about HW “Tell Them Who You Are,” that Roger praised); Grandchildren: Vanessa Winters, David Wexler, Jonathan Schmidt (wife Adrian), Maggie and Jordan Wexler (wife Priscilla). His nieces, among others are actress Daryl Hannah and director Tanya Wexler. His brothers Yale Wexler and Jerry Wexler, and his sister Joyce Isaacs are all deceased. “He sought justice, peace, and understanding of humanity,” Rita added in her e-mail to me. “He used his camera and his compassion that weren’t always available through our media. With Haskell, the art and his heart were one.”

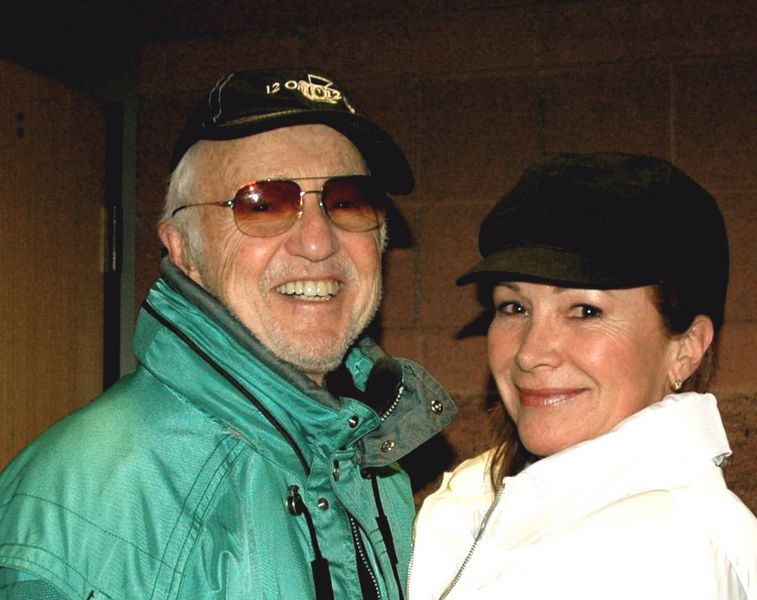

In closing, please enjoy this joyous footage of Roger singing Woody Guthrie’s “Union Maid” alongside Haskell, the late Dusty Cohl, the co-founder of the Toronto International Film Festival, Mary Corliss of MOMA and others…

<span id=”selection-marker-1″ class=”redactor-selection-marker”></span>