It has been a successful year for science fiction, and not just because of box office receipts. “Guardians of the Galaxy” ably juxtaposes space opera with nostalgic pop culture, and “Interstellar” is a return to the genre’s jaw-dropping origins, yet this year’s genuine innovations have little to do with special effects or the allure of a charismatic leading man. In fact, the year’s best science fiction films come from modest means, with budgets so small they qualify as “micro.” “The One I Love” and “Coherence,” both released this year, used their meager scale as an opportunity for strong writing and formal innovations. Both films rely on subjective filmmaking (i.e. from a specific character’s POV) to achieve their effect. These films are involving because they forces us to empathize with an extraordinary situation, which then forces us to care about the characters. When big-budget entertainment gets bogged down by an overabundance of exposition and the trappings of objectivity, these films could provide a lesson on how to make the genre truly exciting again.

When “The One I Love” hit theaters and Video on Demand platforms this August, critics were quick to point out its bizarre, novelty-driven PR campaign. Distributors RadiUS/TWC actively tried to stop critics from discussing the plot, arguing it would ruin the experience, and it got to the point that the film’s co-star Elisabeth Moss joked about the hush-hush PR campaign during a The Daily Show appearance. Flavorwire’s Jason Bailey summarized the issue succinctly:

[The distributors] are trying to make the film’s mystery its draw… but context doesn’t matter; it’s a gimmick, all of it, sheer salesmanship. And such a cynical approach ultimately does this fine, modest, thoughtful picture a real disservice.

The word “disservice” is exactly correct since the marketing push draws attention away from the film’s wicked satire, and its powerful use of subjective filmmaking.

“The One I Love” is about Ethan (Mark Duplass) and Sophie (Moss), a couple who attempt to salvage their marriage at a gorgeous, abandoned couples retreat. They discover a peculiar quality about the property’s guest house: if either Ethan or Sophie enter it alone, they find that an artificial, idealized version of their spouse living inside. Director Charlie McDowell shoots the film like a cross between a romantic comedy and an especially brainy episode of “The Twilight Zone.” At first, it’s mostly clear which version of Ethan and Sophie we see, then McDowell blurs the line between person and avatar, teasing Ethan and Sophie with the possibility of an easier future. For anyone who has experienced the ebb and flow of a long-term relationship, “The One I Love” is an uncomfortable reminder of how we might constantly disappoint our partners.

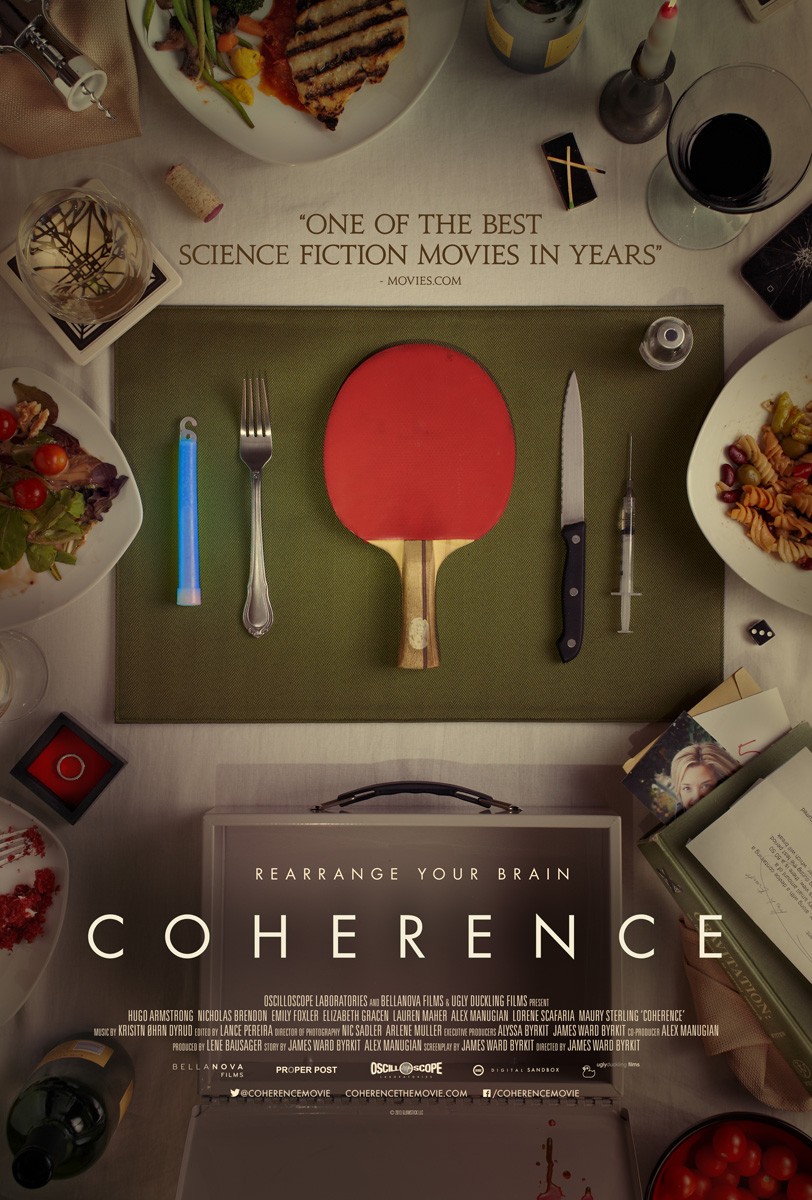

While “The One I Love” uses merciless science fiction logic to tackle modern relationships, “Coherence” is more about existential dread. Both films center around privileged people at about the same age, yet “Coherence” is slightly more ambitious and baffling. Making his feature-length debut, director James Ward Byrkit follows a group of friends over the course of a dinner party. A comet flies over the party, which creates a quantum mechanical paradox as a side effect: there are seemingly infinite iterations/clones of the party guests, and there is no way of knowing whether the “real” one will still exist once the comet passes (in other words, every character is Schrodinger’s cat). Byrkit films mostly from the inside of the house or from one character’s perspective, which creates a gnawing sense of suspense: if there are several other versions of “you” wandering about, then those other versions might be a threat. The characters in “Coherence” cannot trust their friends, and despair when they cannot trust themselves. By keeping the action at an eye-level, Byrkit invites the audience to join as party guest of sorts, which then forces us to asks the same uncomfortable questions they do.

Although these two films delve into different sub-genres of science fiction, they use thrift as an opportunity, not an obstacle. McDowell and Byrkit reveal their hand in a similar, deceptively simple way: they shoot a scene specifically from one character’s point of view, forcing them to see, consider, and finally acknowledge that their double is real. The audience comes to the realization concurrently, alongside the character, which is a canny way to generate involvement and suspense: we trust one character’s experience, so it’s maddening when another character cannot understand it. Byrkit and McDowell use this perspective as a springboard for manipulation: there are moments where we understand what’s going on more than the characters, as if we’re smarter than the movie, then the writing/direction makes a lateral leap in logic that we cannot anticipate. This challenging back-and-forth is science fiction at its best: it takes a supernatural conceit, makes it digestible with playful dialogue and storytelling, then uses that conceit for bigger, slightly terrifying ideas. “The One I Love” and “Coherence” are more than mere entertainment: they’re films wrapped up in philosophical puzzles, with characters we come to care about because the puzzles scare them as much as they scare us.

There is one big-budget science fiction film this year that dared to challenge its audience like its micro-budget counterpart, and it’s not Christopher Nolan’s wormhole epic. Doug Liman’s “Edge of Tomorrow” is brimming with high-tech action, yet its POV manipulation is what makes the film unique. Tom Cruise plays Cage, an everyman who gets stuck in a time loop, repeating the same alien invasion over and over, which helps him transition from a coward to a super-soldier. This is a riff on the “Groundhog Day” premise, except Liman and his screenwriters toy more with the audience’s grasp of the narrative. There are moments where we understand Cage’s situation better than he does, and then there are powerful scenes where the reverse happens, and Cage reveals the sad depths of his knowledge. He speaks with ironic regret, a common emotion in science fiction, because the time loop gives him the opportunity to digest the futility of his efforts. Liman’s camera and hero take turns with who is the genuine objective observer of events, a pattern that engages our minds first and sympathies second. Edge of Tomorrow ends with a climatic chase and shoot-out, although its true subject is how an ordinary man can learn to be good, even heroic.

“Guardians of the Galaxy” and “Interstellar,” arguably the two most successful science fiction films of the year, are imperfect because they use objectivity as a crutch. “Guardians” is a comic book adaptation, with director James Gunn’s camera serving as an omniscient narrator of an origin story, and its multi-protagonist story make it difficult to shift to one character’s subjective experience (recent entries into Marvel’s Cinematic Universe have similar aesthetics, so formal innovations are not likely). “Interstellar” has a more intriguing misstep because director Christopher Nolan eschews subjectivity in favor of exposition. By the time his hero Cooper gets stuck in the fifth dimension and saves humanity, Nolan’s screenplay overanalyzes the specifics of the climax; instead of preserving character development or a sense of mystery, Nolan removes plot inertia in order to explain objectively the minutiae of plot mechanics. With Liman or even McDowell and Byrkit behind the camera, the climax to “Interstellar” would be more similar to “2001: A Space Odyssey,” engaging our curiosity of the unknown instead of our need for comfort (the expository dialogue ultimately presents a time paradox like an elegant proof, not a scientific mystery). The year’s best science fiction is not a triumph of spectacle or special effects, but a testament to the genre’s storytelling flexibility. There will always be an audience for space opera and space exploration, yet they’ll never be as compelling as a POV shot that trusts us to consider the unfathomable alongside a frightened hero.