When Jean-Paul Sartre wrote “hell is other people,” he wasn’t talking specifically about the insidious experience of being a teenage girl, but any survivor of high school will likely tell you, he might as well have been. Teendom is a unique form of torture that has fascinated artists for centuries, and nowhere is the beguiling nature of youth more apparent than in cinema. After John Hughes painted the teenage dream as a series of tall tales injecting magical realism into stifling suburbs, Sofia Coppola captured the kaleidoscopic misery of adolescence in “The Virgin Suicides.” The best films about being young capture something about what it is to be fearless and fearful at the same time, caught between childish things and the desire to grow up at break-neck speed. As Bo Burnham’s examination of middle school malaise “Eighth Grade” hits cinemas, it’s worth considering the breadth of films that examine the teenage experience—but more pertinently, the films that speak to the politics that come with it.

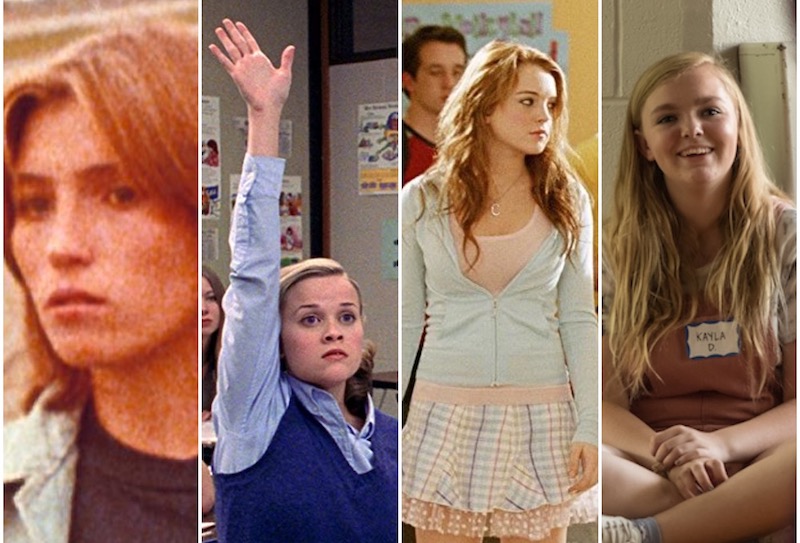

When you’re navigating the numerous pitfalls of growing up, the real world doesn’t always play a huge part in your thinking. Often everything comes down to the unique microclimate of high school, which is heaven or hell depending where you fall on the arbitrary spectrum of teen cool. (Reputations have been made or broken on the strength of a halter top.) For others, adolescence is defined by the experience of avoiding formal education altogether—yet the politics always remain, as visible in or out of the classroom as they are on a cinema screen. “Eighth Grade” understands this—but so too do three other coming-of-age stories of the past 30 years: “Out of the Blue,” “Election,” and “Mean Girls.” Context of production matters for people and movies alike, and examining these films across the decades helps us to understand a deceptively simple question: what does it mean to be a teenage girl at any given political moment?

In 1980, against the backdrop of North America’s worst economic depression since 1929, Dennis Hopper created a film about growing up in blue collar bleakness. “Out of the Blue”’s classic tagline says of its teenage protagonist Cindy “Cebe” Barnes (played by a snarling, surly Linda Manz) “She’s 15. The only adult she admires is Johnny Rotten.” This technically isn’t true, as Cebe’s idol is arguably Elvis Presley – she wears a denim jacket emblazoned with his name and gels her hair into a quiff, emulating his iconic look. Her father Don (Hopper at his miserable best) is fresh out of prison following a long service for causing a collision between his truck and a school bus. Cebe was in the truck with him at the time, as he drank and she sang, and the children on the bus screamed seconds before impact. Within her turbulent childhood, defined by her father’s alcoholism and violence and her mother’s drug addiction, her only constant has been the King. She deadpans at one point, “Elvis died … I’m gonna kill myself so I can go visit him,” but no one believes her.

In fact, the adults in Cebe’s life seem to humour her teenage angst—in their small town, her father’s infamy overshadows her acting out. She sneaks into bars to drink and smoke and screams “Disco sucks!” and “Kill all hippies!” but no one’s really paying her attention. The tragedy of “Out of the Blue” is how Cebe is present and forgotten at the same time, trying so desperately to fight for the affections of parents who act like children themselves. She’s desperate to grow up, but in one scene she crawls into bed after experimenting with drugs, and begins to suck her thumb. She’s just a kid, and it’s heartbreaking to come to the realisation no one cares about her, or worries about her. Cebe doesn’t even care about herself—the world’s given up on her, and she’s given up on the world.

The world hasn’t given up on Tracy Flick. The peppy protagonist of Alexander Payne’s 1999 black comedy “Election” is the antithesis of Hopper’s heroine—played by Reese Witherspoon, she’s blonde and bright with designs on being student body president, a chipper cog in the high school machine. Nearly two decades on from economic turmoil, America was flying high again, but when the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal broke in 1998, political disgrace rocked the country and almost pushed the President out of the White House. Tom Perrotta wrote his biting high school satire long before the country knew who Monica Lewinsky was, instead inspired by the 1992 presidential race between Ross Perot, Bill Clinton, and George H. W. Bush, but Payne began filming as impeachment proceedings began against the President. This combined with “Election”’s production by MTV give it a unique providence, and position it as the perfect blend of politics and pop culture.

Although he claimed to have never thought about it at the time, there’s some delicious irony in Payne casting Ferris Bueller himself (Matthew Broderick) as the enthusiastic, scheming high school teacher Jim McAllister, but the film belongs to Witherspoon’s perky, calculated Flick, who embodies the idea of the teenage girl as smiling villain—at least, that’s what Jim McAllister would have the viewer believe. Her decision to run for student body president speaks to her political ambition, but within the context of a high school in Omaha, Nebraska, the race between Flick and her political rivals becomes comical – a small-scale, slapstick vision of the battles being fought in Washington daily. For Flick, politics are everything. After all, she has designs on Capitol Hill.

But Payne makes it impossible to forget that, all things considered, Tracy Flick is still a teenage girl. In a fit of rage she tears down the campaign posters of her rival, the amiable football jock Paul Meltzer. She’s frustrated by his effortless popularity which jeopardises her chances of winning the election, and when it seems that she has lost, she bawls in her bed, devastated. At the film’s close, she reflects on a successful year as Student Body President, and seems melancholy, reflecting on the fact no one signed her yearbook. Tracy’s loneliness might in part be self-inflicted, but Jim McAllister’s perception of Tracy Flick as an overachieving master manipulator is farfetched. His fixation on teaching her a lesson is in fact his downfall, as McAllister becomes the very scheming diplomat he perceives his teenage nemesis as. Tracy Flick was a nasty woman back when Hillary was in the White House and Trump was just a television personality.

The concept of teenage girls as military tacticians endured beyond Payne’s satire. In 2004 “Mean Girls” captured the imaginations and hearts of a generation of high school students the world over, powered by Tina Fey’s sharp script, based on the self-help book Queen Bees and Wannabes (which in turn warned against the dangers of clique mentalities in high schools). The titular “Mean Girls”—or Plastics—are Regina George (Rachel McAdams), Gretchen Weiners (Lacy Chabert) and Karen Smith (Amanda Seyfried). When ingénue Cady Heron (Lindsay Lohan) joins them, she’s indoctrinated into a world of short skirts and make-up tips, boys and group calls as warfare. In one notable scene, Cady uses a multi-way phone conversation with her friends to cause a rift—an orchestration with split-screens to rival something from a spy thriller.

These duplicitous creatures are not unlike Flick, though should perhaps be considered the higher link in the high school food chain. They are the girls Jim McAllister worries about—the savvy sexual manipulators who know how to play the system to their benefit, and to them, high school is the centre of the universe. Reputations are made and broken by the Plastics (see: the pariah status of Regina’s former best friend, Janis Ian) who write cruel observations about their classmates in a tome called ‘The Burn Book.’ It’s the McGuffin which drives the whole film forward, but also an approximation of all the graffiti scrawled on bathroom stall walls. Yet if “Election” presents high school as the Roman Forum, for “Mean Girls,” it’s the colosseum. Boomkat’s cover version of Blondie’s “Rip Her to Shreds” says as much in an early scene, and Cady’s background growing up in the African savannah means that she sees the politics of high school in comparison to the laws of the food chain rather than Flick’s perception as high school as congress.

But in casting actresses in their late teens and early twenties to play high school students, both “Election” and “Mean Girls” present a less authentic picture of teenage girls. They are fictionalised, distorted versions of reality that show less an authentic portrayal of adolescent life, and in the instance of “Mean Girls,” reflect the fantasy every awkward girl wanted to live out: being beautiful, confident, and ultimately having the whole world figured out at 16.

In Bo Burnham’s debut “Eighth Grade,” no such teen bravado exists. The decision to cast 14-year-old Elsie Fisher as 14-year-old middle schooler Kayla Day positions Burnham’s film as a realist creation, moving away from the vision of school as warfare. The only majori visual similarity is a pool party scene, in which Kayla sees the tableau of her peers in slow motion, a landscape of gleaming flesh and shrieking, smiling popular girls. Burnham sets this to a thumping bassline and the implication is clear: it’s a jungle. Like Cady Heron at the mall envisioning her peers as animals at the watering hall, or Alexander Payne’s decision to use a track from Ennio Morricone’s Navajo Joe score as a recurring motif in “Election,” wryly pitching the Flick-McAllister rivalry as a Western duel.

In “Eighth Grade,” navigating the social pressure of school is framed as a fairly boring – but nonetheless overwhelming—experience, and in 2017, conference calling has been replaced by social media. Endless scrolling illustrates the reality of growing up online, and Kayla spends most of her time at home filming video blogs on topics such as ‘How to be confident’ and ‘Putting yourself out there’: the very skills she wishes to master herself. Rehearsing small talk in the mirror and making lists of her goals (tame objectives such as ‘get a best friend’ and ‘get a boyfriend) speak to a different, gawkier experience than the likes of Cebe Barnes, Tracy Flick, or Cady Heron. Burnham resists the temptation to portray Generation Z’s social media dependence as vacuous or evil—instead, it’s a warm-hearted study in growing up in a world where increased connectivity doesn’t always translate into connection.

Yet the politics of the real world keep creeping in, beyond Burnham’s focus on teendom’s social media habits. Nowhere is this more prominent than in a scene which depicts an active shooter drill at Kayla’s middle school. While a teacher runs them through the drill, the teenagers look at their phones or snap their gum, disaffected by the notion of a school shooting. For Kayla, the drill is simply a convenient excuse to speak to the boy she has a crush on. The suggestion that this is such an entrenched part of everyday life for teenagers in 2017 that it barely registers as an event speaks to the experience of growing up in present-day America, where there have been 316 gun-related incidents in schools since 2013. This underlines the fragility of youth in a way that certainly “Election” and “Mean Girls” do not, instead casting teenage girls as limitless, potentially immortal beings. By contrast, “Out of the Blue” shows the other end of the spectrum from all three: violence is language for Cebe Barnes. Violence is a way of life.

Sexual violence in particular plays a role in “Out of the Blue,” when it’s revealed that Cebe was abused by her father, and her actions since (in emulating punk-rockers and rejecting any sort of femininity) suggest an attempt to make herself invulnerable. The relationship between Tracy Flick and her teacher Dave Novotny within “Election” also speaks this teen fragility. Although Flick sees herself as worldly, and insists that her relationship with Novotny was built on them being intellectual equals, a relationship between a 17-year-old girl and a teacher “twice her age” (according to McAllister) is indicative of a major abuse of power. In “Eighth Grade” we see a more common experience, between Kayla and a boy four years older than her, who instigates a game of Truth or Dare, and instructs Kayla to remove her shirt. When she becomes uncomfortable, he gets angry, and claims he was only trying to help her “be good” for the boys she will encounter when she gets older. “Don’t you wanna be good?” he hisses, as Kayla apologises profusely. The insidious way he plays on her innocence and frames it as a flaw resonates, as one considers the prude/whore problem which dominates coming of age movies. In “Mean Girls,” female characters are either sluts, virgins, or (in the case of misfit Janice Ian) “dykes.” Even when Tina Fey’s Ms. Norberry delivers her climatic speech, in which she pleads to the assembled teenage girls, “You all have got to stop calling each other sluts and whores. It only makes it okay for guys to do it,” she’s correct in that using sexuality to shame a woman or determine her value isn’t useful, but there’s a strange secondary suggestion at play: that women are responsible for how men perceive them and their sexual activity. It’s only in recent years that woman within society have begun to call out this culture—in the wake of Time’s Up and #MeToo especially, the onus is on men to change their behaviour.

Together these films provide a series of insights into the secret life of the American teenage girl from the 1980s to the present day, but it’s interesting to note that these stories were written (with the exception of Tina Fey’s “Mean Girls”) and directed by men. Payne’s “Election” stands out for being a deliberate portrait of teenage lived as perceived by an increasingly out of touch adult, while “Out of the Blue,” “Mean Girls” and “Eighth Grade” all centre their young protagonists as the heart of the story. These films reflect the context of their production, from “Out of the Blue'”s bleakness underwritten by Hopper’s stumbling, slurring performance as Cebe’s abusive father—to the mesmerising, social media-melee of “Eighth Grade.” Together they provide snapshots of youth in revolt that speak to specific moments in time, but also the universal nature of adolescence: all the comedy, tragedy, and most of all, aching vulnerability, that comes with growing up.