Jim Jarmusch has built a career making films that dwell on the very things writing teachers advise their students to skip. He’ll spend a minute observing a man driving and listening to music, without saying anything (“Broken Flowers,” 2005). He’ll show you people walking through a city without saying a word (in multiple films). He’ll have a scene where someone sits alone in a room, just reading or thinking, or a scene where two or more people sit in silence, barely moving, until one of them turns the page of a newspaper they’re reading (“Stranger Than Paradise,” 1984) or swats a fly on a countertop (“Mystery Train,” 1989).

For many viewers, this kind of movie is not only dull but also enraging. They’ll come away from them saying, “It was boring. Nothing happened.” Reactions to art are rooted in personal taste, of course, so it’s not wrong to feel that way. But it is possible to ask them to give the movie another try, because it’s examining things that movies rarely show, in a way that might put a new frame around life.

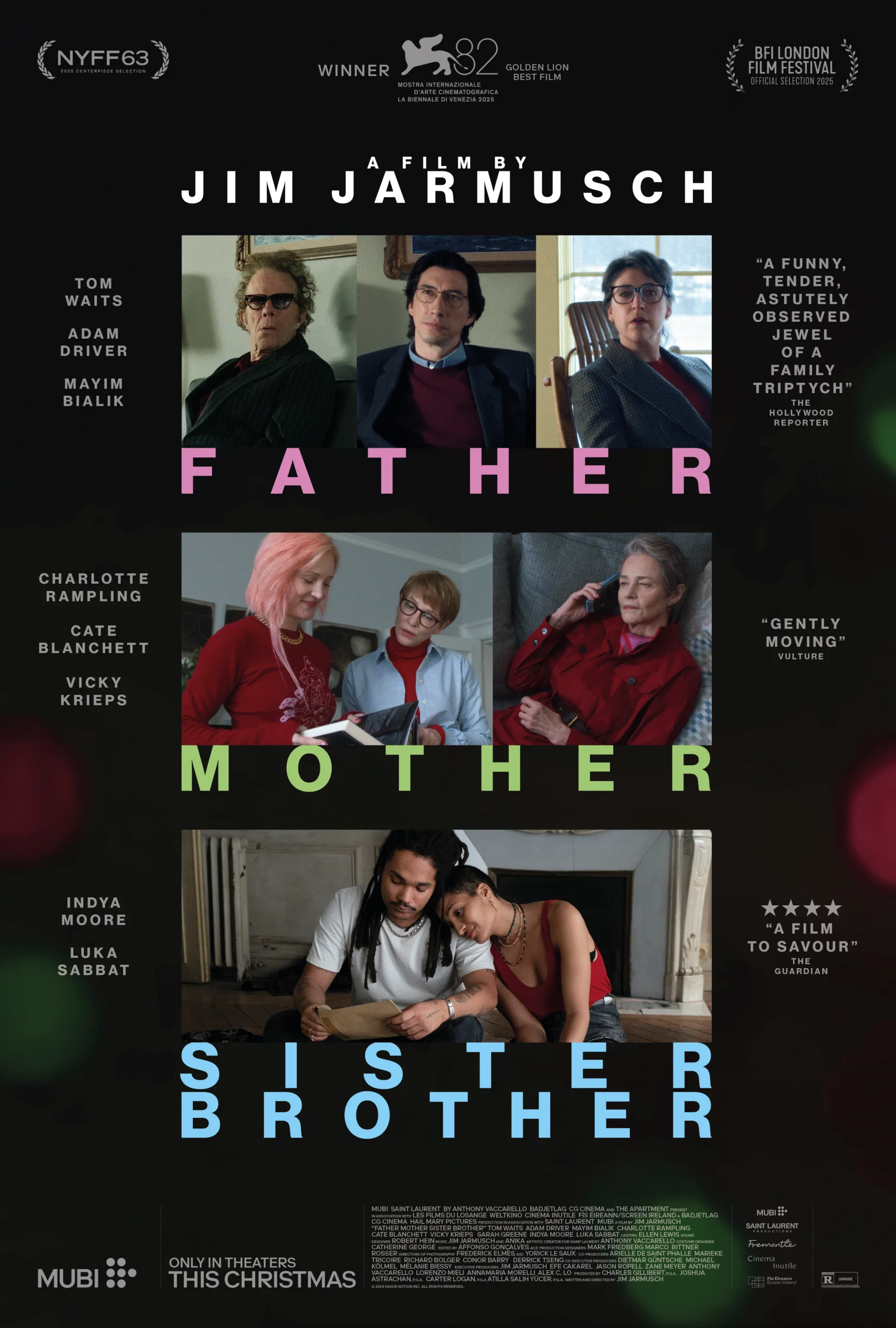

“Father Mother Sister Brother,” Jarmusch’s anthology of three short films about adult children and their parents, is that kind of movie. It’s stripped-down Jarmusch, revolving mainly around people discussing events in their family’s past that are never dramatized for us. It asks the audience to imagine or intuit a lot. We’re dropped into each story as if by parachute. Even when characters talk about people who aren’t present, their words only tell you how they feel about the person. And they often approach complex subjects by talking around them.

The first story finds Jeff (Adam Driver) and his sister Emily (Mayim Bialik) driving into the snowy hills of an unnamed East Coast community to check up on their elderly, widowed father (Tom Waits, a longtime Jarmusch actor and soundtrack contributor). The first ten minutes cover the last part of their drive to Dad’s house. It’s a vivid depiction of adult siblings anxiously approaching a visit with a parent who makes interactions difficult, not by being unpleasant, but by politely refusing to engage. It also gives us that fraught moment of gathering one’s nerve before entering a place where one no longer feels at home. Most strikingly, once Jeff and Emily are in their father’s house, the movie captures those congenial but detached conversations between not-quite-estranged family members in which every earnest but awkward attempt to move beyond pleasantries lands between the speaker and the listener and flops like a fish until it dies.

“He’s always been a character,” Emily says afterwards, adding, “Really mysterious.” What we’ve seen of their father suggests no such thing. Nevertheless, there are some hilarious, inexplicable moments, as when the siblings, who are worried about their father’s health, ask if he’s on any drugs, meaning prescription meds, and he launches into a thorough list of illegal drugs he hasn’t done, including fentanyl and horse tranquilizers. The payoff to this episode is brief but drily funny, and like the endings of the other stories, it might make you imagine the feature film about these characters that Jarmusch chose not to make.

The second story is set in Dublin. A mother (Charlotte Rampling) has invited her grown daughters, Timothea (Cate Blanchett) and Lilith (Vicky Krieps), for their annual visit. Why only annual? The movie doesn’t flat-out tell us, but from everyone’s behavior, we get the gist. The mother is an accomplished novelist. She seems demanding and imperious, in her soft-spoken way. Lilith presents herself as a successful “influencer” who’s got amazing things going on professionally and is on track to marry a rich and handsome man. But we know from the opening of the segment–in which her junker of a car breaks down and she leans on a friend for a ride, then tells her mom and sister that she arrived by lift—that she’s lying about her status.

We never get a handle on Timothea, or “Tim,” as she’s called. But it’s clear that she’s been in a lifelong competition with Lilith for their mother’s affection, one that she probably lost in early childhood. When Tim starts to tell her mother that she’s been promoted, Lilith cuts her off with an excited summary of her latest (possibly made-up?) achievements. The mother’s questions are interrogatory to the point of seeming adversarial. But are they? Or is that just how she talks? Let’s just say that, as in the first segment, there’s more going on beneath the parents’ cool surface than the children are allowed to see, and the depths are conveyed with a shot of a character thinking.

The third segment takes us to Paris. Adult twins Skye and Billy (Indya Moore and Luka Sabbat) are grieving for their parents, transplanted New Yorkers who recently died when their private plane crashed. They’re trying to get the family’s affairs in order. That includes cleaning out the apartment where they grew up and moving furniture and mementoes into a storage locker. Billy did the grunt work; Skye came in at the end. The bulk of this story focuses on the twins driving around Paris while discussing their family history and their parents’ personalities, and reminiscing in the now-empty apartment while looking at old photos. Moore and Sabbat have a warm, genuine chemistry that will feel real to anyone who’s close to their sibling and enjoys their company. Like the other major characters, they aren’t particularly eloquent, just straightforward and smart. But a couple of outwardly unremarkable lines land hard—Billy’s philosophical segue, “Each moment is each moment,” and Skye saying quietly, to herself as much as to her brother, “Life is so fragile.”

Like the other stories, but more so, this one asks us to imagine what is described or suggested. That makes the experience of watching “Father Mother Sister Brother” more like listening to a song that tells a story, reading a novel, or attending a minimalist theater production than watching a typical mainstream movie that tries to put everything right in front of you whenever it’s feasible. Many screenwriting gurus insist that showing is always superior to telling, even though some great films are driven by dialogue and/or narration. This movie is another argument for reconsidering that maxim. It shows by showing people telling.

Some readers may take this review not as a recommendation but a warning to stay away. Jarmusch would be OK with that. He’s an iconoclast who has never once given the impression that he cares about anyone’s opinion on what he should or should not do. Still, it’s helpful to think about where Jarmusch is coming from. He’s very Zen in his attitudes about everything in life as well as art. He’s also a musician who collaborated with Annika Henderson on the movie’s gently trippy drone-rock and synth-scape score. In interviews, Jarmusch is adamant that, no matter what medium he’s working in, he’s not trying to execute a plan or advance an agenda, but to listen to his instincts and open himself up to all possibilities, hoping to land somewhere unique.

There’s a spiritual strain running through all of Jarmusch’s work—part theology and part quantum physics, with shades of lamentation for humanity’s limitations and affection for their delusions and foibles. All that is present here as well. The movie is not trying to give advice, answers, or make a statement. Still, something about the approach makes it feel as if hidden knowledge is being transmitted, and that you can connect to it or learn from it if you stay tuned to the movie’s wavelength.

The combination of Mark Friedberg’s production design, Frederick Elmes and Yorick Le Soux’s cinematography, and Catherine George’s costumes (by way of Yves St. Laurent, which helped fund the production as a showcase for their own work) provides information nonverbally. Notice in the middle segment how the mom and Lilith both have tops that are the same rich shade of red, but while Tim has an identically shaded blouse, it’s partly obscured by a light blue unbuttoned shirt; notice, too, that when the mother gives her daughters parting gifts in paper bags, Lilith’s bag is a shade of pink that complements her ensemble. At the same time, Tim seems to reinforce his anxiety about being the less interesting daughter, the one who has less in common with the parent.

The interstitial material that begins and ends the film and separates the three stories is scored with Jarmusch and Henderson’s music, plus quasi-experimental imagery that suggests celluloid bleaching out as a film reel ends, plus VHS scan lines and other visual and aural distortions. These short bits are incantatory and entirely non-rational. They suggest a non-physical means of transportation, not from one place to another, but from one experience or mindset to another. They’re of a piece with recurring elements in the script that are never explained, like the skateboarders who appear in every segment, whose graceful movements suddenly shift into slow motion; and the repetition of bits of information across stories, such as the Rolexes possessed by characters in the first and third segments.

What’s it all about? What’s the conclusion? What’s the takeaway? Jarmusch never hands us anything. We’re left to think about all of it, how it might or might not fit together, and how we relate to it. The constant is that Jarmusch feeling of getting fixated on elements of narrative and visual storytelling that most other filmmakers actively avoid or just never include. It’s unsettling, in a way—as if the normal experience of moviegoing has been turned inside-out. You may be left cold, feeling that you’ve seen a theoretical exercise whose purpose was never articulated. Or you may react as I did. I took pages of notes for this review, doing my best to describe the movie as a discrete work—an object to be contemplated. When the final credits rolled, I closed my notebook and wept.