The Washington Post’s long-running exposé on the burglary of the Democratic National Committee’s office in the Watergate Hotel not only brought down a sitting President, forcing Richard Nixon’s resignation in August of 1974, but it also codified, to a certain extent, the image of the investigative reporter. Or rather, two images of the investigative reporter. Straight-arrow, starchy collared Bob Woodward, still a prolific author and soberly sagacious television talking head, and somewhat more gonzo Carl Bernstein, a personality sufficiently idiosyncratic that he was credibly portrayed by Dustin Hoffman on the one hand (in “All The President’s Men,” adapted from Woodward and Bernstein’s nonfiction bestseller) and Jack Nicholson on the other (in “Heartburn,” adapted from Bernstein ex-wife Nora Ephron’s roman a clef best-seller.)

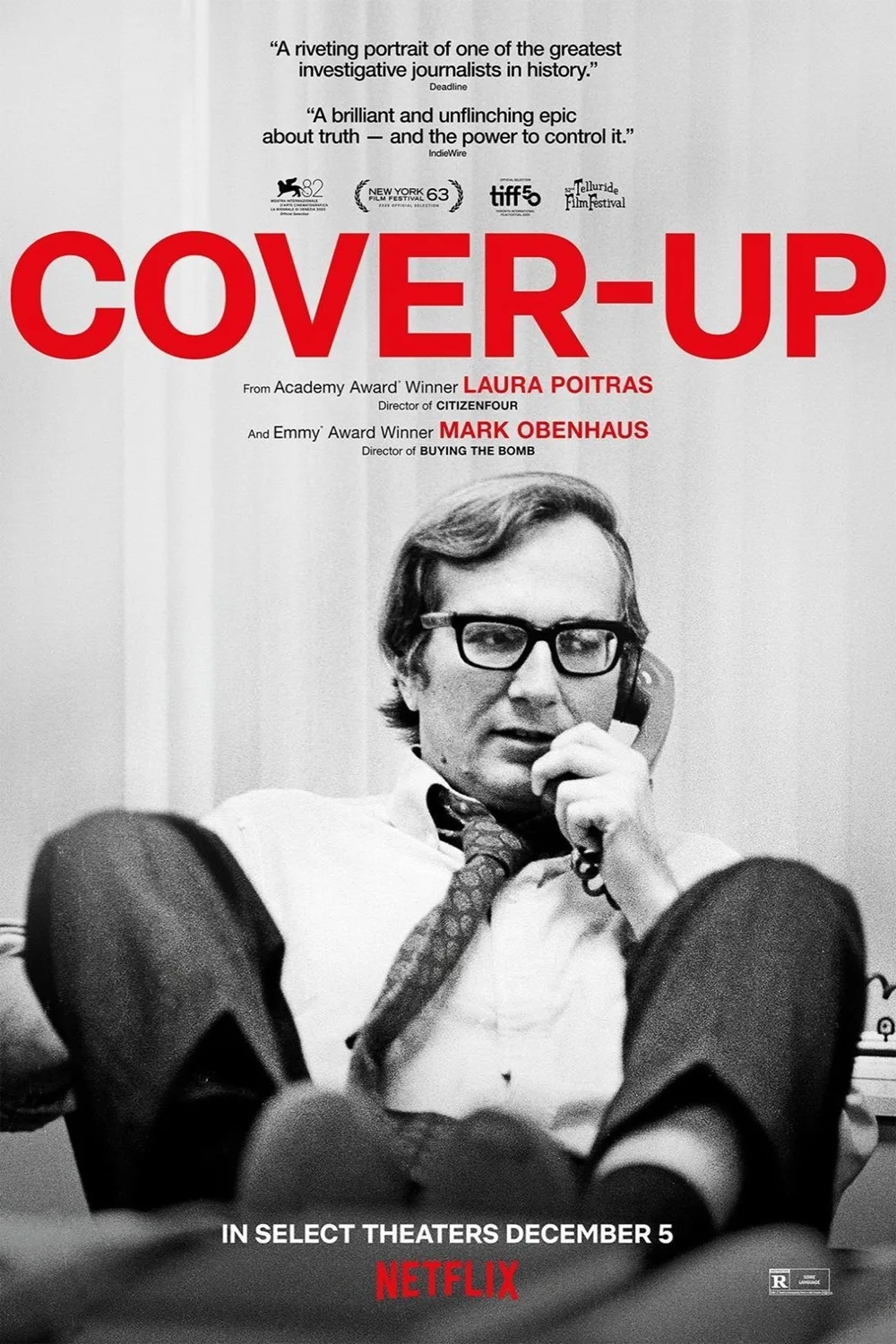

Many investigative reporters are not quite so colorful. Or perhaps it’s more accurate to say that they may be colorful in different ways. Pioneering documentarian Laura Poitras provides a reasonably thorough and cinematically satisfying account of Seymour Hersh, a longtime investigative reporter whose commitment to truth hasn’t waned since the 1960s, when he covered various snafus in Vietnam. Poitras won an Oscar for her cinematic portrait of a different kind of whistleblower, Edward Snowden, in 2014’s “Citizenfour.” But from where I sit, her masterpiece is 2022’s “All The Beauty and the Bloodshed,” a remarkable chronicle of art and activism, focused on the work of the photographer Nan Goldin in both fields.

As we learn in the film, Poitras approached Hersh, whose work spans the eras of My Lai through Abu Ghraib and continues to this day, to sit for her camera two decades ago. Hersh’s journalistic story begins even before his scoop on the My Lai massacre in the early ‘70s. He was inspired by the newsletter muckraker I.F. Stone and, at the Associated Press, got on the Vietnam beat and worked it like a dog with a bone. He found out about the U.S. bombing of civilian targets, for instance. When he broke the story of the My Lai massacre, he syndicated it through the Dispatch News Service. Hersh won a Pulitzer Prize and was hired by the New York Times. He covers a lot of this in his own 2018 book “Reporter.”

But by putting the garrulous, sometimes cranky Hersh on film, “Cover-Up” reveals, in the behavioral sense, the obsessiveness that makes an investigative journalist. And also the painstakingness that has to be a coeval to obsession, lest psychology defeat the actual digging necessary. Some of his greatest scoops, Hersh tells Poitras, came out of nothing but a single name. It’s this doggedness that makes Hersh such a compelling figure. And to add to that, he’s socialized or interviewed practically every major historical figure of the post-World-War-II 20th century. And, as Poitras admiringly notes, he’s still at it: you can subscribe to his Substack, where he publishes a newsletter.