On January 29th, 2024, the Israeli Army ordered the evacuation of the Tel Al-Hawa neighborhood in the Gaza Strip. On that day, six members of the Hamadeh family, along with their six-year-old niece, Hind Rajab, were trapped in their car after the Israeli Army opened fire on them, killing five occupants of the vehicle immediately. Miraculously, a fifteen-year-old girl named Layan was able to call the Palestinian Red Crescent Society and ask for help before she too succumbed to her wounds. That left six-year-old Hind alone in the car, surrounded by the corpses of her slain family members, possessing a cellphone with shoddy reception as her only hope.

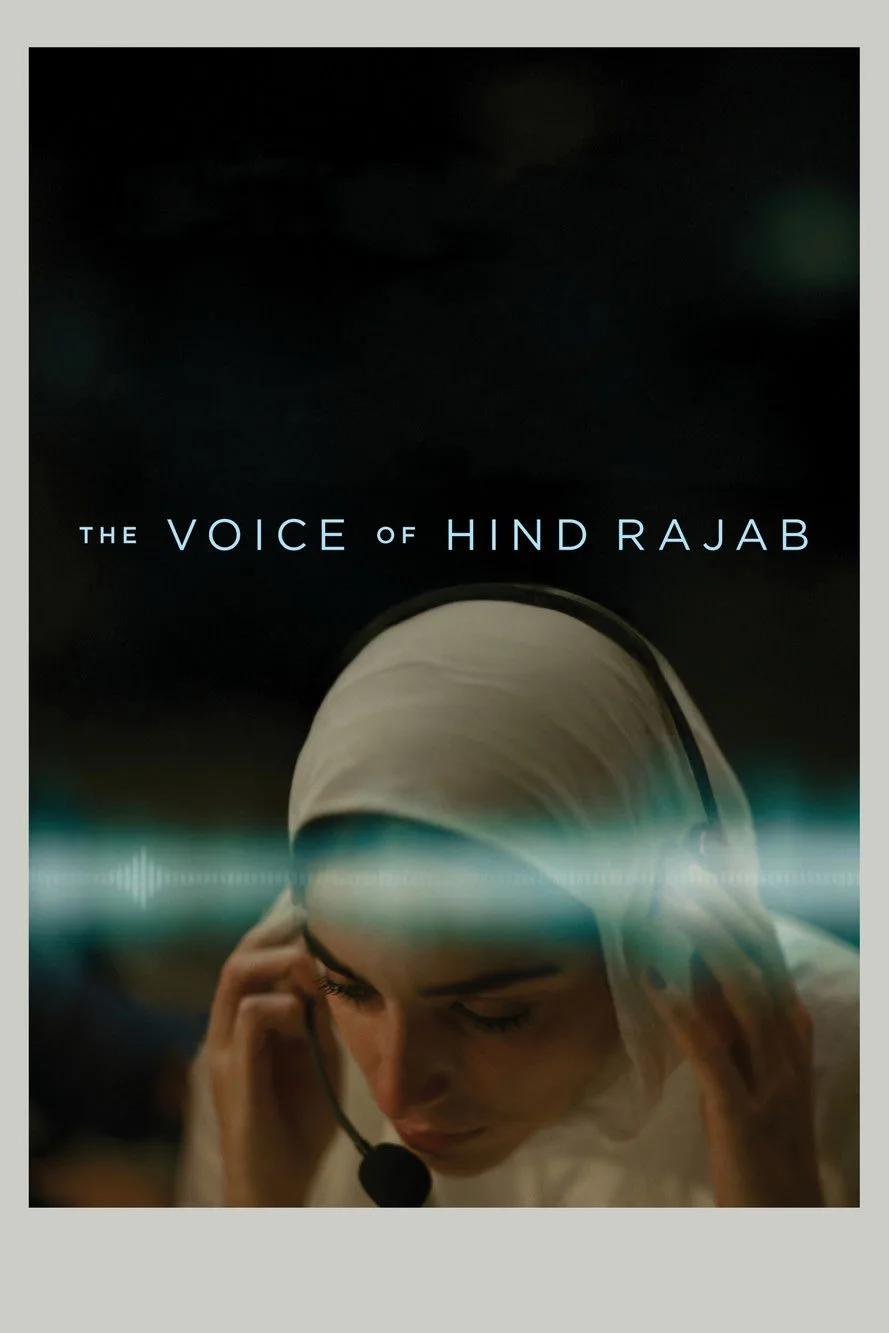

“The Voice of Hind Rajab,” the latest film from Kaouther Ben Hania, whose previous films “The Man Who Sold His Skin” and “Four Daughters” have both been nominated for Oscars, is a soul-stirring docudrama based on Hind’s phone calls with the PRCS as they worked to coordinate to save her life. The film premiered at the 82nd Venice International Film Festival, where it won the Grand Jury Prize. It is one of several films by and about Palestine that have received festival launches this year, including Annemarie Jacir’s expansive drama “Palestine 36,” which premiered at TIFF, Cherien Dabis’ epic tragedy “All That’s Left of You,” which debuted at Sundance, and Sepideh Farsi’s immersive documentary “Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk,” which first screened at Cannes.

Two of these films dramatize the historical past: Jacir’s film is set amidst the Arab revolt against British colonial rule that took place from 1936 through 1939 during the Mandate period in the country, while Dabis’ epic follows three generations in Palestine from the Nakba in 1948, the occupation of the territories after the 1967 Six-Day War, and the First Intifada in the late 80s and early 90s. Both “Palestine 36” and “All That’s Left of You” aim to reclaim history from a Palestinian lens. In contrast, Farsi’s documentary, which records her year-long friendship with Palestinian photojournalist Fatma Hassona during the current invasion of the Gaza Strip before her untimely murder by the IOF, just a day after the film was accepted into Cannes, centers the history being made right now.

All three films are heavily dependent on archives, either those that live in oral histories, or those that were recorded, be it in song, by still photography and motion picture cameras, newsreels and newspapers, or via the oral histories passed down from one family member to the next. It is in these personal and official archives, many of which have been destroyed by the Israeli government over the years, that the enduring resilience of the Palestinian people holds steadfast. Farsi herself created an archive of her friend’s life through her own footage, the promotion of Hassona’s art, and even her memories of her family. It is in the place where archiving becomes an art form in and of itself, where the heart of Kaouther Ben Hania’s film lies.

Framed in an ultra-widescreen ratio, Ben Hania uses a spectrogram to visualize the audio files, allowing Hind’s authentic, small, fragile voice to, at times, envelop the whole screen. The widescreen ratio allows each of the Red Crescent aid workers–gentle Rana (Saja Kilani), spirited Omar (Motaz Malhees), straightlaced Mahdi (Amer Hlehel), and calming Nisreen (Clara Khoury)–to occupy the frame at the same time, as they work in tandem to coordinate Hind’s rescue. Aside from one sequence where Ben Hania seamlessly blends her docudrama with real footage of the office as filmed for social media, her filmmaking remains mainly in the classical vein, relying on close-ups of her actors’ faces as they run through the gamut of emotions while talking to Hind through the worst of her life, or as they attempt to keep it cool while working through the bureaucratic nightmare of red tape it takes to coordinate a rescue in a restricted zone. As such, the film plays like a chamber drama, focusing on those Red Crescent workers working tirelessly to save her life, with Hind’s voice connected through a weak telephone line, one that the Israeli Army often jams.

The choice to focus solely on the office is powerful for several reasons. For one, it doesn’t turn Hind’s distress and eventual martyrdom into a bloody spectacle. Much like Farsi’s choice to center her film solely on her filmed WhatsApp conversations with Hassona, keeping her friend’s face almost always in the center of the frame, Ben Hania’s choice to keep the violence of war outside the frame, heard only through blasts of gunfire through the phone line, forces the viewer to focus on the matter at hand: Hind’s life. There is no bloody imagery to scroll away from, like you might have done on social media. There is just her voice, and the faces of those who are desperately doing everything they can to save her. The viewer, like these Red Crescent workers, must sit with Hind and bear witness to her distress, to her singular pleas for help, for her life.

This structure also lays bare the bureaucratic red tape these aid workers must navigate to do their job. The car in which Hind was trapped with her six deceased family members was a mere eight minutes away from the nearest Red Crescent ambulance, yet to follow “protocol to the letter,” as Mahdi says, it takes them three hours to “coordinate” with the Israeli Army, at first via the Red Cross, and later through the Ministry of Health, to secure a safe route for the ambulance, and then a green light from the IOF which is the final sign off the need in order actually to use the route to go and rescue her. This is administrative violence, a concept that may be hard to grasp when it remains theoretical. Still, as we watch it play out in near real time, the violence becomes just as hard to watch as it would be if Ben Hania had placed the camera in the car with Hind as the bullets from the nearby tank rained down on her family.

Lastly, the structure dispels the idea that there is a “right way” to navigate the Kafkaesque complexities of an oppressive regime, as is made plain by the ultimate fate of Hind and the two ambulance first responders, Youssef Zeino and Ahmed Madhoun.

Early in the film, while still stuck in the mire of this violent red tape, the Red Crescent office turns to social media, releasing audio from the calls and photographs of Hind as a way to elicit international outrage, hoping the outside pressure would lead to that elusive green light. When I first watched the film, I wondered how its drama would play out for audiences who do not know how it ends. Does the tension play like exploitation? I can’t answer that.

For me, it brought me back to that horrible day last January. It was during Sundance, and I was torn between doing my job as a film critic, screening films via the festival’s online platform, and following Hind’s plight on Instagram, knowing full well most of the people in the festival bubble might not know anything about what was happening a whole world away. Watching the film again as we head into awards season, this cognitive dissonance has not yet left me. Not a day has gone by that I haven’t thought of Hind and the life that she was denied. Ben Hania’s film asks you to do the same: to remember her smile, her voice, her love of the sea, and her.

With that act of remembrance in mind, I am also reminded of “With Hasan in Gaza,” a film by Kamal Aljafari made from footage he shot on MiniDV tapes in 2001 during the Second Intifada, as he searched for a man he’d been imprisoned with a decade earlier. While filming families on the beach, a group of kids asks Aljafari to turn the camera towards them, pleading with him because they wanted a photograph of themselves. Like Aljafari’s use of the footage of these children serves as proof of their existence, so too do the audio files of Hind’s pleas with the Red Crescent aid workers act as an archive of not only Hind’s existence, but also of the cruel system that facilitated her untimely murder.

Hind’s life ended in martyrdom, and “The Voice of Hind Rajab” exists not just as a clarion call to say never again, it also asks you to sit with this violence. Not with the bloodshed, not with the abstraction of a number in a news article. But with this violence. The physical, mental, and administrative violence that was inflicted on this young girl, who, like so many of her peers, should still be here today.