When it comes to the Palestinian genocide, it is simple for our brain’s processes to be overwhelmed in viewing the constantly rising numbers of casualties and expansive horizons of destruction. But it is a privilege to be a witness and not a victim. It is a privilege to be overwhelmed by numbers and images rather than barrages of bombs and the loss of loved ones. It is a privilege to view these tragedies as generalized amongst a population, rather than an amalgam of unique lives. Iranian filmmaker Sepideh Farsi’s “Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk” is not simply a documentary, but a poignant individual’s record. It is a reminder that every number we see on the news is a complex web of individuality. It’s historical sonder on screen.

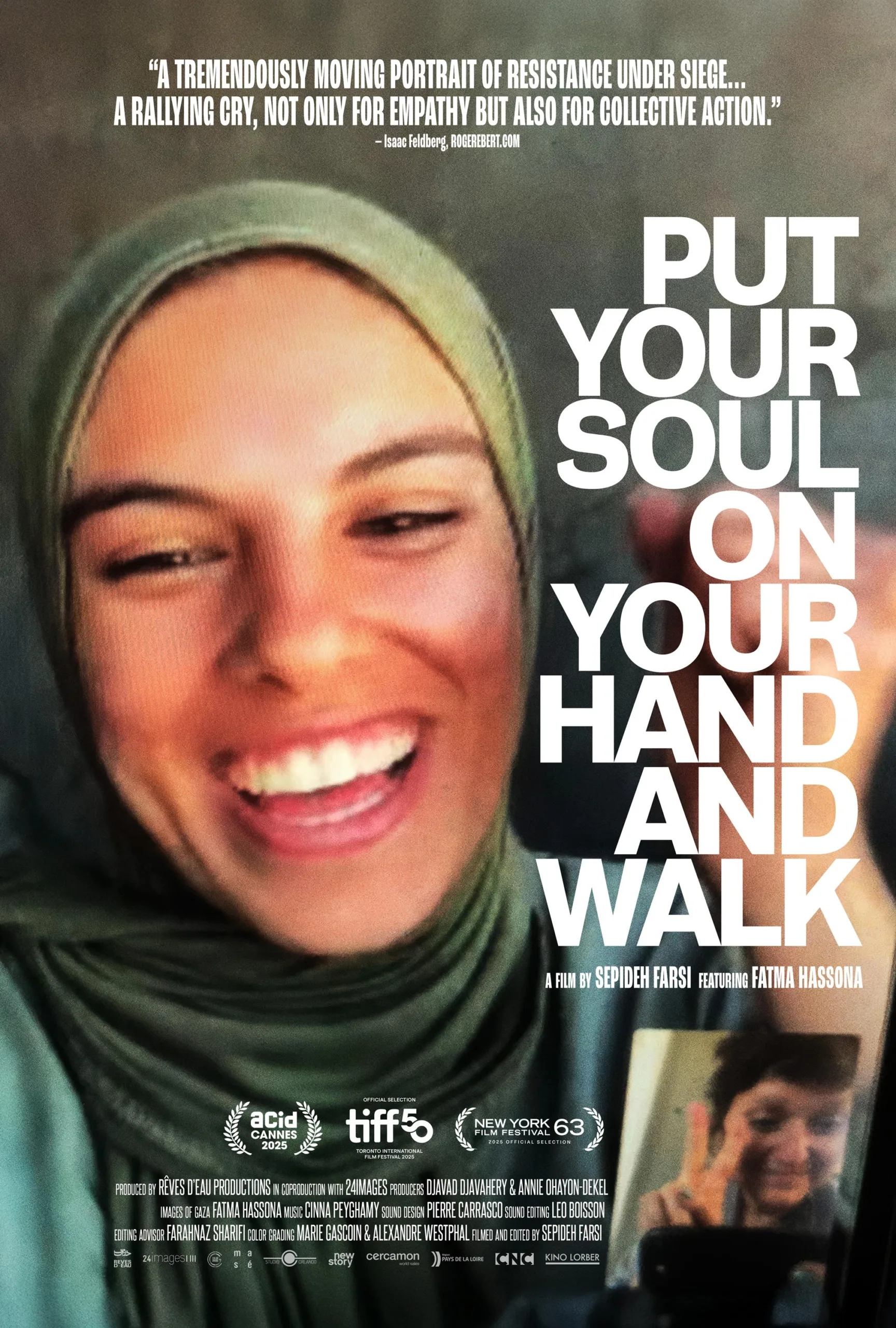

The film follows the relationship between Farsi and a 24-year-old photojournalist, Fatma Hassona. Taking place over WhatsApp video chats, interspersed with Hassona’s photographs and news media updates on the state of the “war,” Farsi’s film prioritizes the personal while still allotting asides for context. But this film belongs to Fatma, her resilience, and her enthusiastic smile, which never fade upon each answered call.

These calls, screens filmed on Farsi’s own iPhone, are marked by a palpable distance: screen through screen through screen; jittery audio, freezing frames, and grayed out reminders of poor reception. This distance, however, never feels cold or hopeless, as Fatma’s unwavering optimism and glowing smile greet nearly every moment, and in total, define the film. She giggles at the sound of the beach heard over Farsi’s call (she resides by the ocean), even as drones hum in her own locale.

Every time the phone is answered, it’s a miracle, and, even as Fatma’s eyes grow tired, the jubilant smile never leaves her face. She describes witnessing days of bombings, and when asked immediately after how it feels to be a Palestinian in these times, she responds without a beat: proud. Over time her dreams fade from visiting Tehran and Rome to tasting chocolate, and Farsi’s film reminds us that violence is the robber of dreams, lives, and culture, but not faith.

Even in describing that she is not leaving her home, by way of caution of the snipers stationed in Gaza, she smiles that she is not afraid. She smiles as she shows the photos of the 13 loved ones she has lost, the youngest only a year old. These smiles are discordant to the horrors she describes: her relentless (and baffling) positivity becomes a beacon. Farsi serves as a realist, never raining on Fatma’s shine, but skeptically affirming her optimism, the same way we as viewers do. To be fair, Farsi is stuck. Fatma is only within digital reach, and, even then, just barely. What else is there to say or do to a woman under violent occupation, other than to plead to the metaphysical? To cross your fingers to her prayers?

The rigidity of her hope is both inspiring and tragic, confounding and desired. As hopeless bystanders to history, we fear that we know how this story will end. And our fears are given credence, as we come to find that 24 hours after being told that their film was selected by Cannes, almost a year to the date since these calls began, Fatma and her family were killed in their homes by a targeted Israeli airstrike.

“Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk” morphs from a memoir to a eulogy. It’s an epitaph to Fatma’s life and a document of grief, Farsi’s and ours, as the woman we’ve come to know through brilliant photographs, touching poems and song, and her unshakeable spirit, is mortal, and yet now, immortalized. But the sickness takes root in our guts as this film, a memorial, is not enough. It’s certainly a gift to have come to know Fatma, to give face and life and desire to a population overly generalized in the face of terror. But it is also a reminder that so many more like her still exist in this genocide, and that it is still ongoing. It is a call to action. And if we can be prompted to honor Fatma by way of adopting some of her hope, “Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk” may not be enough to stop the action, but it will always be a record of a history under attack, and this preservation is radical.