The long-running NBC newsmagazine series “Dateline” started out as a venue for investigative pieces on all kind of subjects, much like its inspiration, CBS News’ “60 Minutes.” But after a while, it became clear that the stuff that made the biggest ratings impact tended to focus on violent and often lurid crimes, so that’s what the show increasingly specialized in. “To Catch a Predator,” a “Dateline” spinoff, ran from 2004-2007 as an occasional series of specials, twenty in total. It focused exclusively on attempts to identify and apprehend child predators. It was controversial for both extreme methods and shaky ethics. Host Chris Hansen and his team would identify a probable child predator who was fishing for new victims online, then hire young people to pretend to be even younger as they gained the trust of the target and entice them into a public place where Hansen could confront them and authorities could arrest them. The show’s catchphrase was Hansen telling the alleged predator, “You’re free to go,” whereupon he’d be arrested by police as soon as he left the kitchen or living room or parked car where he’d been talking to Hansen.

I wrote about “To Catch a Predator” a couple of times as a television critic at the Star-Ledger of New Jersey, and got blowback from some readers for saying that however noble the show’s intent—which is right there in the title—it got there in a way that seemed more concerned with creating “good television” than actual journalism or defensible police work. It turned journalists into participants in crime investigations and police into tools for journalists, neither of which is good for a supposedly free society. And it routinely veered close to entrapment. When I said as much in print, I got emails and letters from people accusing me of defending abusers. The common refrain was something like, “These people are so horrible that we should have no compunction about doing whatever we have to do to remove them from polite society and make sure they never hurt people again.”

That’s a fine sentiment in the abstract, but it manifested itself as a series built around complicated plots to frame guilty people—or people who seemed guilty. One of the most basic principles of both journalism and police work is that you’re not supposed to do that. But it was hard to make that argument in the immediate post-9/11 period, which is when the United States government decided that anyone designated as a terrorist could be detained indefinitely without a trial, or even charges—and a majority of the public, still traumatized by the carnage in New York and Washington, just wanted to see the bad guys punished, and felt the mission was so important that it was OK if innocent people got swept up.

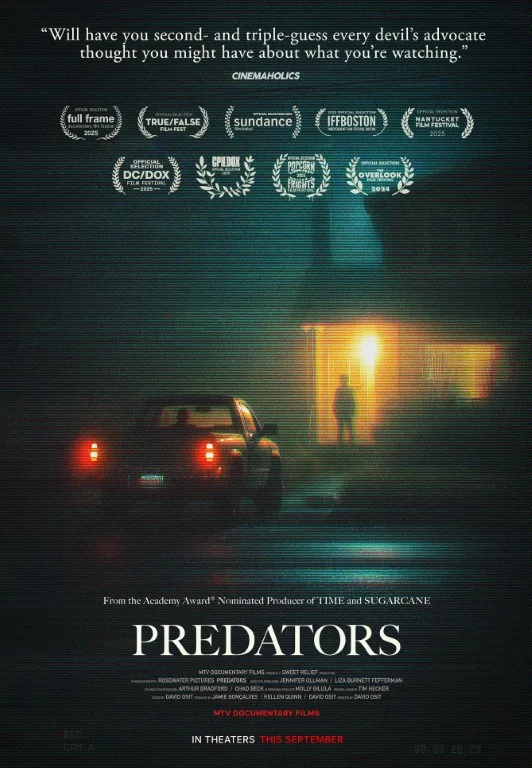

“To Catch a Predator” is the focus of the feature-length documentary “Predators,” by David Osit, who is himself a survivor of childhood sexual abuse. It’s an honorable attempt to grapple with all the different aspects of the NBC show. It is built around uncertainty, which in retrospect what defined every aspect of the series, even though the creators never foregrounded it in a way that would’ve done it justice.

Osit divides the movie into sections that focus on different aspects of the show and the controversy surrounding it. He gives us a sense of what the show was, taking us through the format and the public’s reaction. He interviews performers who pretended to be underage potential victims—often they were only a couple of years older than the people they were pretending to be—and gets their mixed reactions about having participated. (Some of the performers told Osit that they saw photographs of male genitals for the first time while playing decoys.) We find out about the various imitations of “To Catch a Predator,” the vast majority of which now reside on YouTube, where Hansen wannabes practice their own version of ambush journalism, which can seem indistinguishable from vigilantism. Osit also brings a personal dimension via his own experiences, which corresponded with the time period in which the show aired.

“Predators” often seems to be going for an Errol Morris-style, “What is the truth, and what does the word even mean?” approach: equally explanatory and philosophical. It succeeds a lot of the time. But other times seems to get bogged down in tangents that take it too far away from the central issues. Some of these are potentially rich enough to merit their own film, such as the acknowledgment of how tech has mainstreamed conspiratorial thinking and vigilantism-as-content, and the observation that technology has changed so much since the program first aired that we now each have the capacity to not only mount our own version of an investigation into criminality, but distribute the results.

I found it frustrating by the end, because I’m one of those viewers who doesn’t think any crime is so horrible that it merits compromising the ethical practices of the systems that are set up to protect everyone. But this is a case where none of the ground that is being examined is firm enough to plant one’s feet on. In any case, the movie is bound to stimulate conversation, and probably some arguments as well—and since Osit has said that was his goal, it should be considered a success. Be warned, however, that if your own experience in any way matches the experiences of the victims who were championed on the old show and its new imitators, this entire feature should be considered one huge trigger.