Edward Berger’s “Ballad of a Small Player” is one of the most over-directed films I’ve ever seen. And I’ve been playing this specific game for a long time.

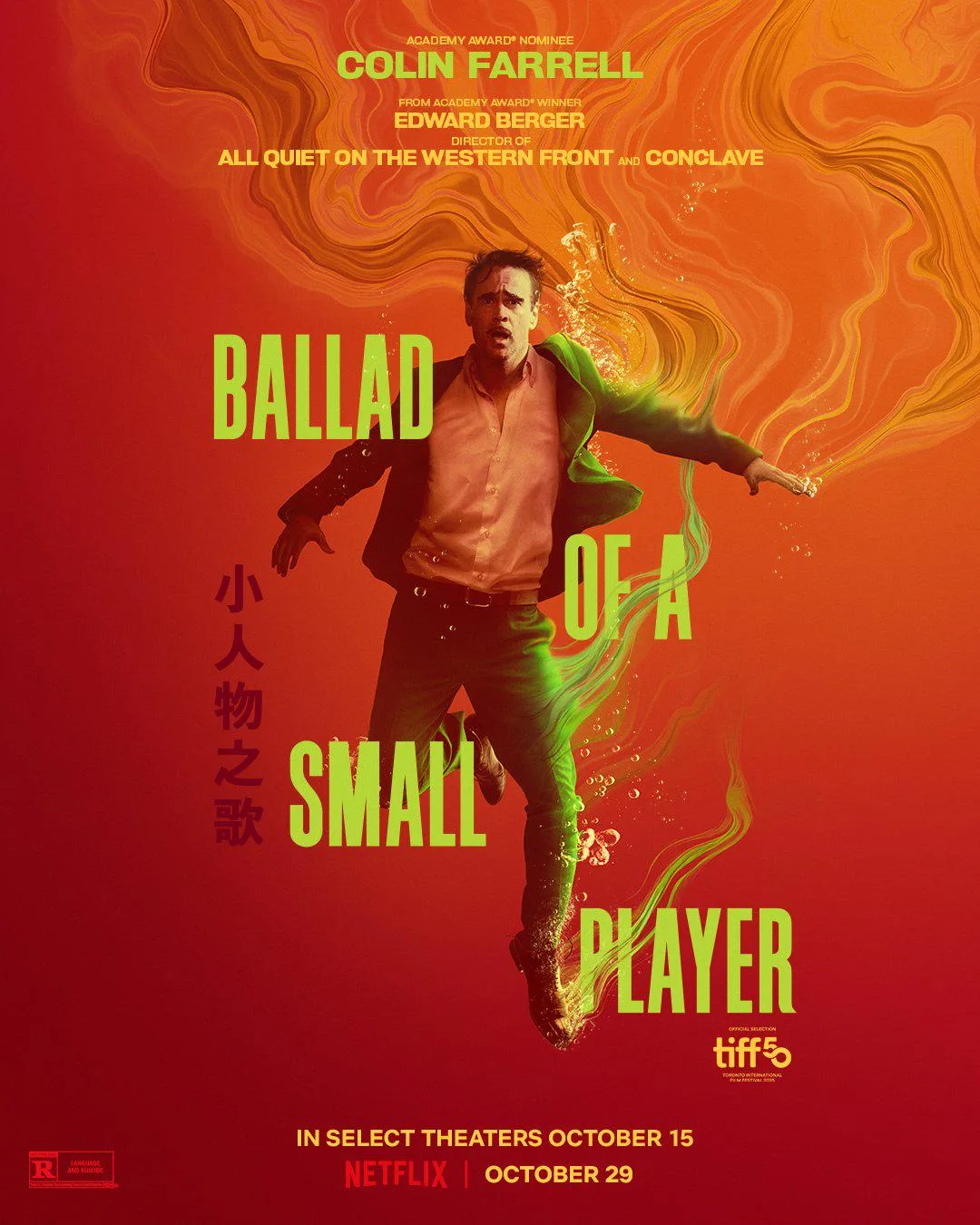

From its opening shots, it aggressively and pretentiously shows viewers all its cards, stubbornly unwilling to delve deeper than its attention-starved aesthetic, overcooked score, and characters who are constantly aware of who they are and what they need. There’s a difference between leaning into the tropes of the “gambler who needs one last win” genre and cravenly, blatantly propping them up as if they’re new again. Colin Farrell has become one of the best actors of his generation (I think he should have won an Oscar for “The Banshees of Inisherin”), and Berger hit back-to-back with “All Quiet on the Western Front” and “Conclave,” which makes this misfire all the more shocking. In both of their histories, it will be considered one of the smaller projects, if it is considered at all.

Farrell plays the entirely fraudulent Lord Doyle in what is essentially a riff on the “Leaving Las Vegas” formula, with an addict on his last legs given a shoulder to lean on by a woman with a heart of gold. We meet him trying to flee a lavish Macau hotel room that’s littered with bottles of champagne, turned-over furniture, and other signs of debauchery. “Small players” don’t afford rooms like this, so one presumes that Doyle was recently on top of the mountain before his gambling plummeted him to a position that he’s trying to escape his debts. The world around her is bigger than ever; he’s the one who feels small.

Doyle makes it out, but he catches the eye of two women on his way down the ladder. The first is Cynthia Blithe (Tilda Swinton), who is revealed to be a private investigator sent by the British financiers demanding Doyle return the many thousands of dollars he owes them. The other is Dao Ming (Fala Chen), one of those sweet-talking casino employees who is basically the drug dealer to addicts like Doyle, extending lines of credit past the moral breaking point. They don’t dig the hole as much as give gamblers shiny new shovels to do so themselves. Dao Ming takes a liking to Doyle for no real logical reason beyond “movie”—she says he’s a “lost soul” as if she doesn’t see those every day—and tries to help this fractured man, but “Ballad of a Small Player” makes it clear that his is unlikely to be a story of redemption through its aesthetic. Berger and his team are more interested in dragging this poor loser to Hell. In fact, he may already be there.

The one thing that remains at least visually captivating throughout “Small Player” is the manner in which Berger and his cinematographer James Friend (Oscar winner for “All Quiet”) turn Macau into the most interesting character in the movie, shooting its massive towers, unchecked opulence, and non-stop flashing lights into a vision that feels like another planet. They love reflections to an overused degree, but it would be a lie to say that “Ballad” doesn’t look good. It just might look too good compared to the hollow nature of everything else.

The problem is that even that mesmerizing backdrop becomes numbing as one realizes that Rowan Joffe’s adaptation of Lawrence Osborne’s book has nothing to say. Not just “nothing new,” nothing much at all. The book drew comparisons to Dostoevsky in its telling of a tale imbued with religious, moral, and philosophical themes that one imagines work better on the page than they possibly could in a film that’s so bluntly in your face as this one. Berger and Joffe clearly intended an approach that would mimic the excess of Doyle’s existence, but that makes his saga impossible to care about. Humanity has been so drained from this experience that when the final act asks us to care about the very soul of Doyle or what happens to him/it, it’s almost entirely impossible.

Again, Farrell doesn’t misstep here. He’s become one of our more consistent actors, and he does his best to ground Berger’s vision—to such a degree that Doyle’s desperate flop sweat starts to feel like the actor’s thwarted attempts too. It’s more that Berger fails him by thinking that excessive behavior demands excessive filmmaking. Like so many actual small players, Doyle gets lost in the flashing lights around him, resulting in a project that never conveys why his is a song worth hearing.

This review was filed from the Toronto International Film Festival on September 11. It will be released on October 15, 2025, on Netflix on October 29.