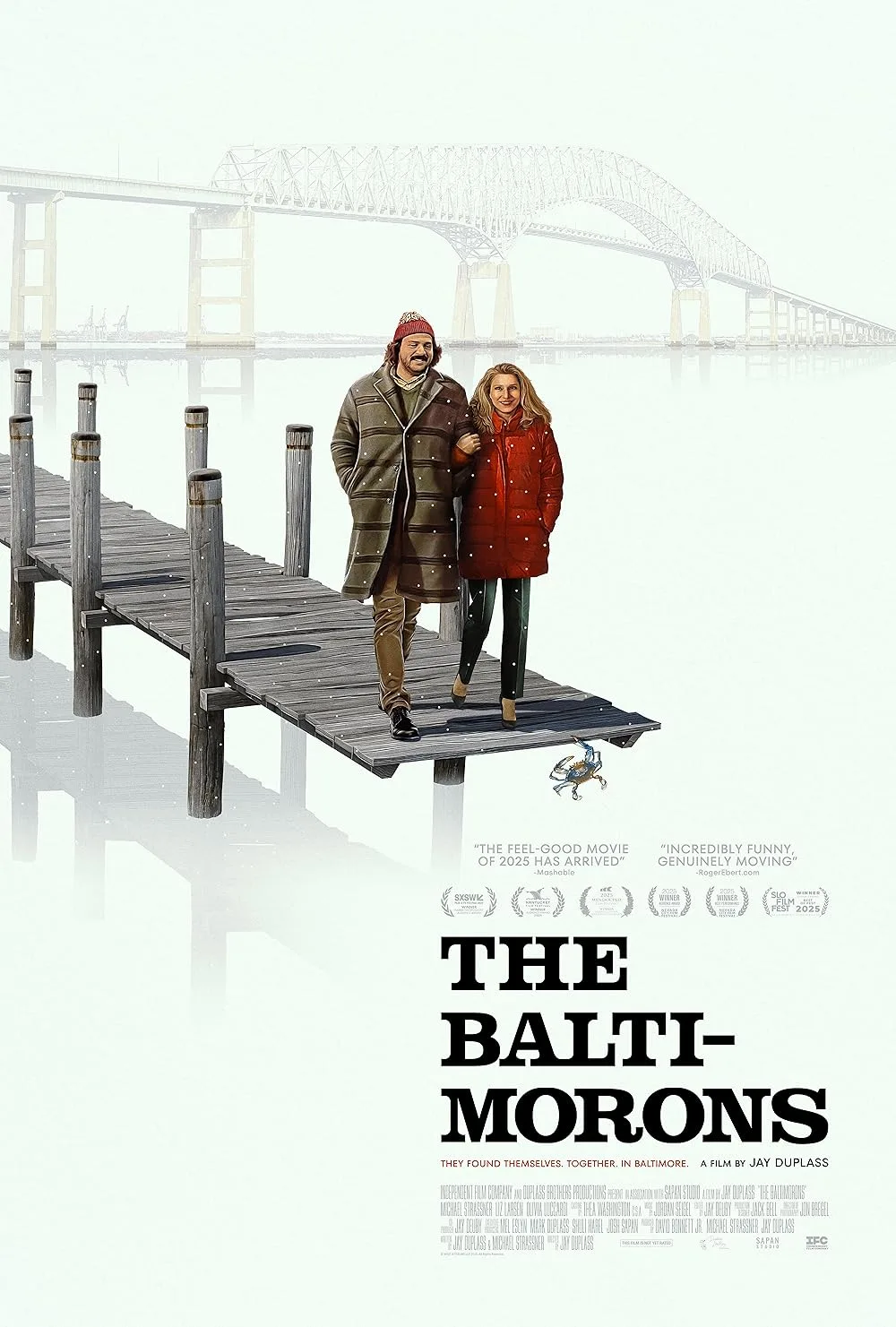

“The Baltimorons” is about a recovering alcoholic and former improv comic who breaks a tooth on Christmas Eve while visiting his fiancé’s family in Baltimore, somehow finds a dentist who will treat him that day, and falls in love with her. The dentist is a bit older than he is, divorced, and depressed because her ex-husband married his new girlfriend at City Hall that morning, which means that every Christmas Eve, she’ll have to think about her failed marriage. When the improv comic leaves the dentist’s office, he realizes that his car has been towed for parking in the wrong place. The dentist offers him a ride to go get his car from the impound lot. Then we’re off to the races, in a quasi-romantic variant of “After Hours” that perhaps stretches itself a little too far, but it is always enjoyable and sometimes quite moving.

The improv comic, Cliff, is played by actor Michael Strassner, who cowrote the script with his director Jay Duplass, a veteran of low- and micro-budget independent film typically made in partnership with his brother Mark. (The Duplasses are actors as well, though Jay isn’t onscreen in this one.) Cliff’s fiancee Brittany (Olivia Luccardi) is a doting partner with saintly patience who cares so much about Cliff’s ongoing recovery and depressive tendencies that she tracks his phone with an app, to make sure he doesn’t go anyplace where he could be tempted to start drinking again, make choices that get him hurt or killed, or spontaneously decide to do himself in. The dentist, Didi, is played by Liz Larsen, one of those “I know her, what do I know her from?” character actresses. I have no recollection of seeing Strassner in anything prior to this. But he’s clearly a natural screen actor who, like Larsen and Luccardi, understands that you don’t have to sell every little thing when you’re acting for the camera, and it’s often better to let the audience come to you.

“If you keep talking, I’m gonna fit you for a muzzle,” Didi warns Cliff when he’s in the dentist chair. But it’s not really a threat. She has a private smile on her face even when Cliff is at his most smack-able. There’s a plastic bit jammed in Cliff’s mouth to keep his lips apart, which cause him to drool uncontrollably when he stands upright and makes it hard for him to pronounce consonants. But that doesn’t stop him from blatantly flirting with Didi, an act that they both know is only partly attributable to the anesthesia.

“His name shall not be mentioned,” Didi says when Cliff asks about her ex-husband. “He was a high school sweetheart who turned out to be a nightmare.” This comment feels like a premonition, or a buried realization that she’s about to embark on a different version of the same road. But what can she do? She likes him. He’s charming, in his shambling, needy way, and he can be cool when he wants to. Mainly when he wants to get laid, but still. And he keeps trying to entertain her, take her side, and raise her spirits. Yes, it’s because he’s got the hots for her, but it’s also probably because making Didi feel better balances out all the moments when Cliff glimpses himself in a reflective surface and thinks, “That guy sucks. He destroyed his life once, and now he’s doing it again.” (When Cliff phones Brittany to tell her his car got towed, she exclaims, “Again?”)

Didi at first wants to ignore what’s happening at her ex-husband’s house, but when she gets a taste of Cliff’s game-for-anything prankster energy, she starts thinking about dropping in. Cliff promised his fiancée that he wouldn’t sneak off to a local improv show organized by his buddy Martin that night (on Christmas Eve? Ok—if you say so). But of course a movie like this can’t mention an improv show that represents a combination homecoming and mea culpa for the main character and not have him attend it. The question is, what will happen there? If you think Didi will end up onstage, congratulations on having seen at least one other movie in your life. A lot of unconscious wishes come true in this movie, for the audience as well as the characters. Didi and Cliff are both good at improv, though only one of them has done it onstage. Didi has to have the improv fundamental “Yes, and” explained to her by Cliff, but the way she behaves when she’s around him, she gets it on a cellular level. Like Indiana Jones says, these two are just making things up as they go.

What follows is one of those personality-driven films where the main question isn’t “Will they or won’t they?” but rather “Who are these people, underneath it all?” The answer, when revealed, feels fundamentally honest. However, there are a few moments where it seems like the movie is trying a little too hard to ensure that you like the hero, who is profoundly self-centered and makes a mess of things from the beginning, digging himself deeper into a hole with every scene. Strassner strikes some notes here, especially in reactive closeups, that are reminiscent of both Charles Grodin and Richard Dreyfuss in their younger years—edgy, unclassifiable actors who were always funny and soulful, even when playing the sorts of people you wouldn’t want to spend five minutes with in real life because they couldn’t shut up and you somehow got the sense that they could turn on you. For connoisseurs of the warped romantic comedy, let’s say that “The Baltimorons” is ultimately more “The Goodbye Girl” than Elaine May’s original version of “The Heartbreak Kid.”

They’re both terrific movies, but the second one is way more comfortable with letting you sit with contradictions than the first one. “The Heartbreak Kid” started with the Grodin character leaving his wife during their honeymoon to chase Cybill Shepherd’s character, who he’d just met. Similarly, we never forget that Cliff has a potential mate waiting for him somewhere else, and that he is deliberately ditching her on Christmas Eve. But also know that he’s hurting from frame one, and as the night goes on, the movie keeps scraping away at Cliff’s hurt, revealing new strata, so that each time he does something so hurtful or stupid that makes us want to write him off, we suddenly get a new tidbit that makes us walk our disgust back a few steps.

The irony here is that the movie is paying into an insurance policy it doesn’t need. Strassner’s unique energy is so mesmerizing that you’d still hang on his every move even if his character were ten times worse. The movie wastes energy ensuring that we like Cliff, even though it’s already doing something more impressive, which is getting us to find Cliff interesting because of his contradictions. To be fair, that’s the film’s approach to Cliff about eighty percent of the time. I merely lament the abrasive depths that Duplass and Strassner decided not to plumb.

This is the best movie Duplass has directed, and he’s made some good ones (including “Jeff, Who Lives at Home,” a failure-to-launch comedy that feels in some ways like a warmup to this). It captures truths that movies rarely portray. There are no internal monologues, but thinking back on the movie, I felt as if there were. The actors’ faces are so expressive that you can imagine what they’re thinking and feeling. “Did I just help this screwed-up man get his life back together, only to have him ditch me during a holiday with my parents?” “I know that he’s treating his fiancée terribly, but I am falling in love with him anyway—is this my fatal flaw? Forget it, he’s cute.” “I just realized that am setting fire to my life because I want to set it on fire, so I might as well keep adding lighter fluid to see how high the blaze can get.”

Didi and Cliff are a fun couple. They seem like kindred spirits. I give them six months.