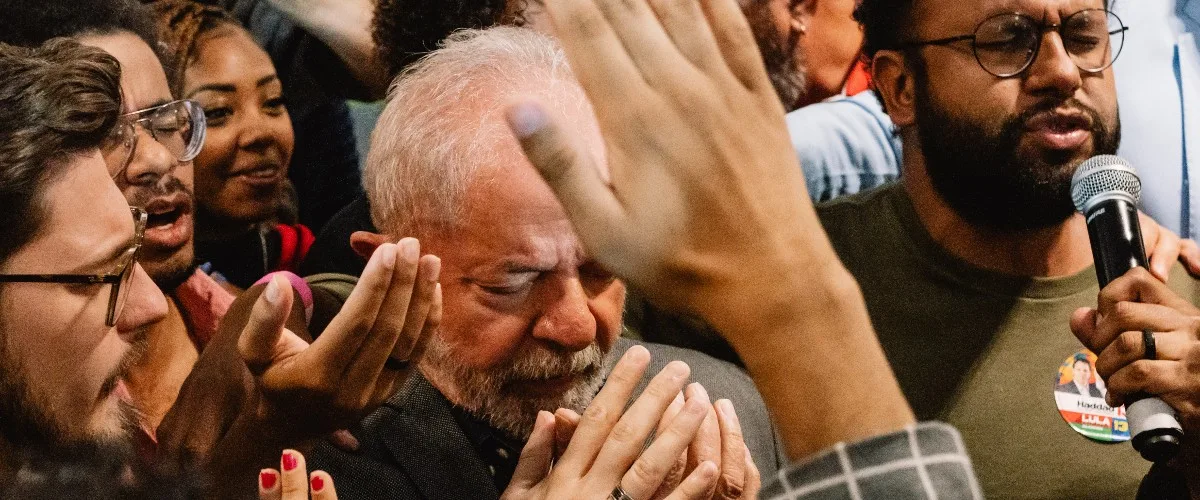

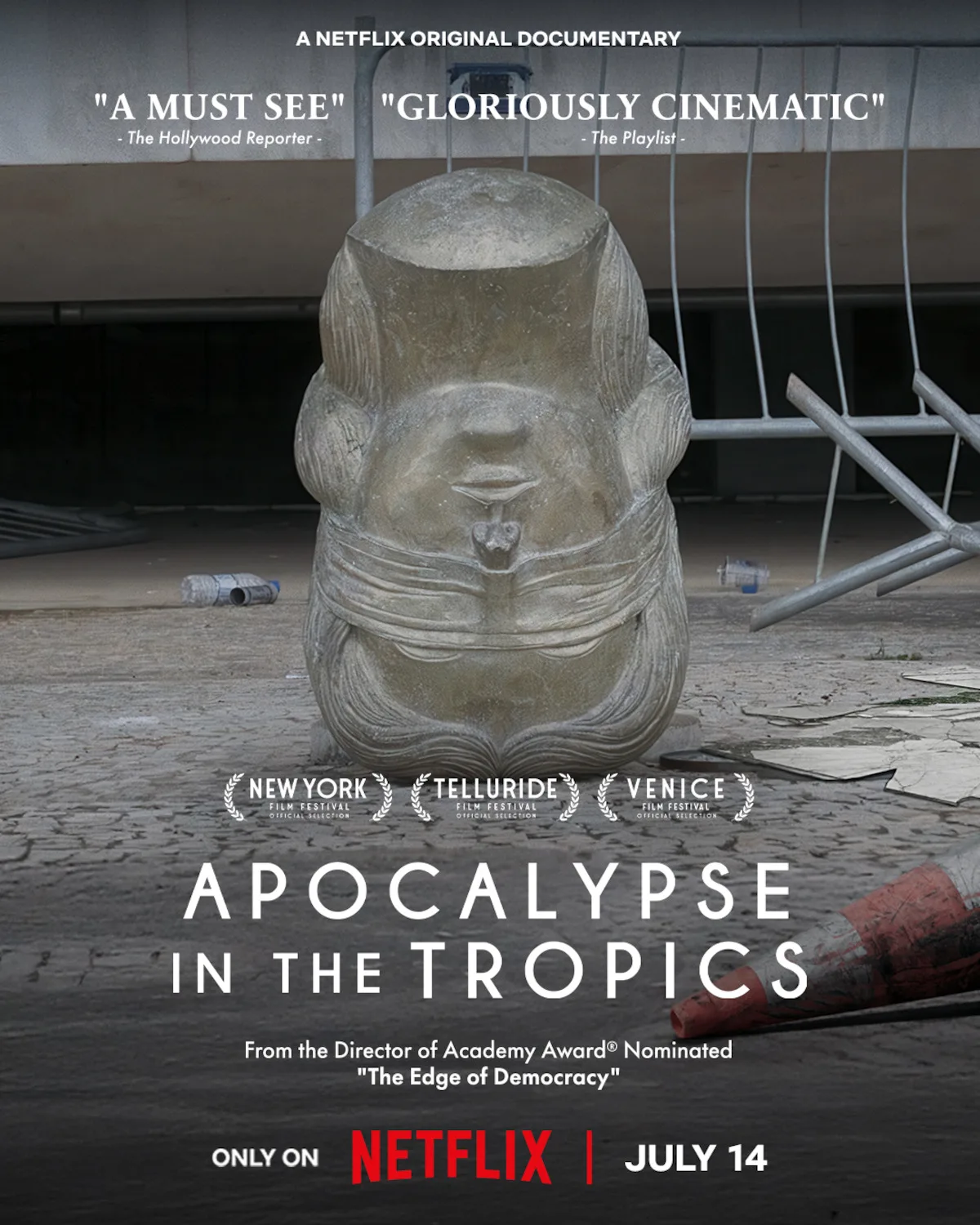

In Petra Costa’s Oscar-nominated 2019 documentary, “The Edge of Democracy,” the filmmaker captured history in the making. While following the rise of her home country’s workers’ party, she landed candid conversations with many of Brazil’s top political figures, making international headlines, especially then-outgoing president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and his successor, Dilma Rousseff. Then, their political house of cards came toppling down in a series of scandals that forced Rousseff out of office and imprisoned da Silva. In the chaos, a cocky former army captain named Jair Bolsonaro took the reins of power and oversaw one of the most tumultuous times in the country’s recent memory.

In Costa’s equally impressive follow-up, “Apocalypse in the Tropics,” the director once again returns to the political ring, this time to follow a different thread of questioning to explore how Brazil’s once burgeoning democracy came under attack. In “Edge,” Costa retraces her own family’s experiences under Brazil’s dictatorship (which was also the topic of another recent Oscar winner, “I’m Still Here”) and the political waves that shaped the country to where it is today, but in “Tropics,” she takes a step away from the familiar to explore the rise of the evangelical movement in her country and how it fueled the rise of right-wing candidates like Bolsonaro. Gently peeling back her country’s (and our own) history with faith and religion, she finds some dark, uncomfortable answers to who is really shaping the future of her country.

If “Edge” plays like a political thriller, complete with scandals and taped incriminating calls, then “Apocalypse in the Tropics” can feel like a horror movie, uncovering egomaniacal powerbrokers preaching from the pulpit, manipulating their listeners to support one candidate over another. The documentary is a sobering look at the way the political landscape has shifted, illustrating how candidates are no longer just battling it out over government spending and policies, but over performative alliances and pet causes, especially over abortion, which remains illegal in Brazil.

Costa uses Medieval paintings inspired by the Book of Revelation to illustrate not just the descriptions of Hell but also the goal of right-wing evangelical pastors (most specifically in the film represented by a champion of Bolsonaro’s, Silas Malafaia), who call on their flock to disrupt politics as usual. In the short term, it means voting in more conservative evangelical lawmakers to rule in their favor, but in the long run, the goal may be to sow more chaos to hasten the end times.

For those of us who grew up within or around the evangelical movement, either here or abroad, none of what Costa reports is new. What’s interesting is her outsider approach to the subject, laying out the foundations of the belief system, following a figure like Malafaia to show the changing power structure, and tying together seemingly disparate tangents into one more complicated portrait. She learns about the Bible, digs up the Medieval paintings to explain the theological teachings of the movement, and even includes the CIA’s venture into missionary work in Brazil as a way to undermine a then-growing Marxist strand of Christianity. While Costa’s film is firmly rooted in Brazil’s current political scene, it’s easy to see the parallels of growing fascism in many other countries’ backyards, including the United States.

In some of Costa’s earlier films, the filmmaker weaves together her family’s story with poetic narration and evocative imagery, giving her breakout film “Elena” an almost-dreamlike feel between documentary and fiction. “Elena,” which pieces together the life and death of Costa’s older sister, shares DNA with the scrapbook quality of “The Edge of Democracy,” which incorporates her family’s history of hiding from the Brazilian dictatorship and its lasting effect on their lives.

But “Apocalypse in the Tropics” looks and feels like a nightmare from the chilling visions from the Book of Revelations to news footage of crowds storming their seats of government, the breathtaking loss Brazil suffered during COVID, and the First Lady’s frenetic display of praying in tongues. While there are a few jabs at Bolsonaro’s incompetence and the uncomfortable spectacle of his office, much of the time is spent in the company of unelected mission-driven gatekeepers who know their power. Her outsider perspective gives no warmth of familiarity, only the startling realization of what they have accomplished so far and what remains ahead for a democracy trying to regain its footing.