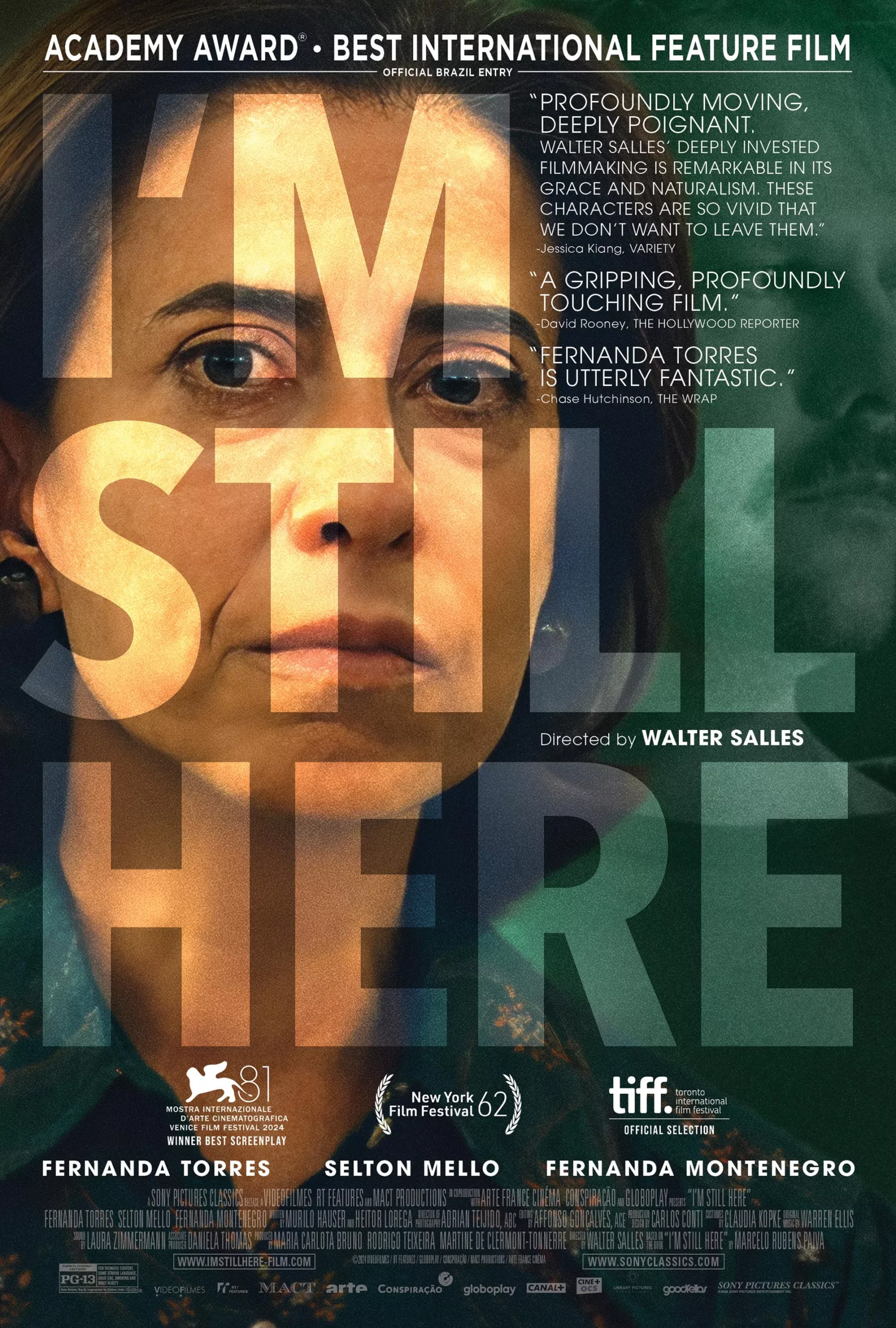

Within the assured wooden confines of a church, a frightful Eunice Paiva (Fernanda Torres), the wife of former congressman Ruben Paiva (Selton Mello), arrives hoping for answers. But not from God. She is confronting her children’s former schoolteacher, who after being arrested, detained and possibly tortured by Brazil’s military dictatorship, is now trying to keep a low profile in a space that offers people spiritual protection. “My husband’s in danger,” says an exasperated Eunice. “We’re all in danger,” retorts the teacher. That pervading risk, the terror felt by a life suspended or ended, took over Brazil during the violent military dictatorship that gripped the South American country from 1964 to 1985. It’s also the tragedy, as felt in Torres’ incredible performance, at the heart of Walter Salles’ engrossing period drama “I’m Still Here.”

The director’s return to politically historic stories—his portrait of a young Che Guevara in “The Motorcycle Diaries” is similarly about an educated figure becoming an activist after confronting harsh political realities outside their bubble—is a feat of tonal control. Because Salles’ adaptation of Marcelo Rubens Paiva’s same-title memoir (the author is the son of Eunice and Rubens) isn’t built on big speeches or sudden moments of eureka. It is immersive and unhurried, and quietly devastating, taking viewers into the origin of a void left in a wife and a mother.

In 1970 Rio de Janeiro, Eunice and Rubens live with their five children by Leblon Beach. With white sand as soft as pillows and blue seas as clear as the sky, the idyllic locale should be a soft landing for the Paiva family. An architect and former congressman, Rubens has only recently returned to the country after a six-year self-exile due to the 1964 coup d’état. For the family, however, the dictatorship is never far from the foreground. Military helicopters fly over the beach, and trucks carrying additional troops occupy the streets. Television news stations cover the release of the German and Swiss ambassadors from anti-government factional custody. Rubens also takes secret phone calls in his office, coordinating pickups and drop-offs of packages.

The younger children, Marcelo (Guilherme Silveira), Maria (Cora Mora), and Nalu (Barbara Luz), barely notice these incursions in their seemingly serene lives. Eliana (Luiza Kosovski), the second oldest, is initially less involved, too. Only the oldest, Vera (Valentina Herszage), who is politically awakening to the point Rubens has decided to send her to London with friends, possesses some idea of the grave danger they’re in. Meanwhile, Eunice, along with the maid Zezé (Pri Helena), simply keep the house. Eunice notices Rubens taking these mysterious calls but doesn’t push deeper; she also listens to the radical conversations Rubens and their friend group partake in but does not offer her opinions. Instead, she makes soufflés. And for a time, Salles, too, is content with absorbing the family’s ephemeral domestic dynamic.

The director’s soft yet detailed touch for recreating the era is exemplified in the cozy architecture of the family’s home. Their house is a bustling, lively space filled with brightness, music, art, and books. it’s a cosmopolitan atmosphere brimming with culture, where dance parties soon become cigar-smoke-filled salons. Fresh hues of forest green, cobalt blue, and marigold yellow vibrate in this vital space. Their daily lives in and around the home are often recorded through epistolary means, 16mm home movies, and personal photography, moments of documenting that will be juxtaposed with the paperless trail the family will soon deal with. By taking time to live inside the family’s insecure bubble, Salles makes the eventual puncturing even more agonizing.

The collapse occurs when Rubens is taken for questioning by plain-clothed army officials, a catastrophe that takes the film to darker places and engenders many unanswerable questions. And while it’s not a spoiler to say Eunice and her children will never see Rubens again, those hopeless queries aren’t necessarily what the movie is about. Rather, this poignant film concerns the response to having neither a definitive answer nor final closure. Eventually, Eunice and Eliana will be taken in for questioning, psychologically tortured, and then released. Eunice will pick up the pieces and dig, becoming politically active in the process. We will follow her struggle through the decades—her career as a professor and supporter of Indigenous rights—leaping to São Paulo in 1996 before settling in 2014.

While these autobiographical facts certainly matter to Salles, they, once again, are not the story. He’s far more interested in the psychological turmoil that occurs from not knowing. Torres’ intricate performance, which often reminded me of Carlo Battisti’s guarded sorrow in Vittorio De Sica’s “Umberto D,” underscores that curiosity. Her advanced relationship to her fellow actors and to the camera relies on the character’s desire to force a kind of normalcy in uncommon times. She tries to be present for her children, for instance, but she can’t hide the mourning she wants to experience from her face.

There is also a telling tension to her new homelife immediately following Rubens’ abduction. Eunice hesitates to tell her younger kids about their father’s fate— “he’s traveling,” she says—opting for a false sense of normalcy built on mistruths. Their home therefore becomes a metaphor for their beautiful country, where daily atrocities enacted by an oppressive government happen on a sun-bleached vacation landscape without a full acknowledgement by anyone of their occurrence.

Salles homes in on these cracks and fissures because he intuitively understands the Paiva family. After all, his father Walter Moreira Salles, former chairman of Unibanco, was the country’s ambassador to the United States before the coup d’état. Though his family moved around during his childhood, Salles certainly sees his milieu in their story. He also understands Torres, whose mother, Fernanda Montenegro, became the first Brazilian actress nominated for an Oscar in Salles’ “Central Station” and briefly appears in this film as the older Eunice. Still, it’s difficult to fully contextualize how incredible Torres is here; she matches the film’s silent grief by keenly deploying her character’s internal angst into her slender frame. Through her formidable presence, the deliberate “I’m Still Here,” a film that locates further meaning in the face of Brazil’s present Far-Right wave, remains in the heart long after the picture fades.