For years, forgive me, I have been telling this story and no one but me seems to find it funny. And yet, I persist:

Back in a previous century, during a visit to Los Angeles, some friends entreated me to join them at a local nightspot to see longtime MGM musical star Ann Miller (“Easter Parade,” and many others) debut a stage show presumably consisting of her greatest hits. It happens, though, that on that same night, “Kiss Me, Kate,” in which Miller memorably costars, was having a very rare 3-D screening in a repertory cinema on Sunset Boulevard. I insisted I was going to the movie, not the stage show, and when ridiculed for my choice, asked rhetorically:

“Who wants to see her in person when I can see her in 3-D?”

You see the subtle irony there? Well maybe it’s TOO subtle. Regardless, I’ve been a fan of 3-D movies ever since, as a kid, I ducked flaming arrows and whipped-cream pies at the Crocker Theater in Elgin, Illinois. I didn’t think movies could get any better. Fortunately, they did. But 3-D still has a big place in my heart, and so I am thrilled at the prospect of World 3-D Film Expo III, running Sept. 6–15 at the Egyptian Theater in Hollywood.

Some of the films in the “expo” have never been exhibited 3-dimensionally in the U.S. before, and some may never be projected in their original form again.

The expo is not to be confused with a 3-D “festival” playing in downtown L.A. later in the month; that one consists of only new-age-of-3-D films, like “Avatar” and “World War Z” and so on. And that kind of digital 3-D, I feel, doesn’t have quite the literal depth of the original analog 3-D of the 1950s, the kind that was going to “save” the movies from that ominously encroaching monster, television. Unfortunately, you needed special glasses to see 3-D (though NOT the red lens/green lens kind that came with 3-D comic books) and wouldn’t you know, along came 20th Century Fox’s CinemaScope, the movie miracle “you see without glasses,” as the ads screamed, and the short-lived 3-D fad was shorter-lived than it should have been.

It had offered up a few years of wondrous thrills, however, and yes, one of the pleasures of the 3-D Expo, at least for boomers and those even older, will be evoked memories, a teleportation back to a world when telephones stayed at home and TV shows were pleasantly stupid, as opposed to the grimly stupid ones we have now. Three networks were able to come up with worthwhile programming in about the same quantity as 500 channels are today—but that’s another column.

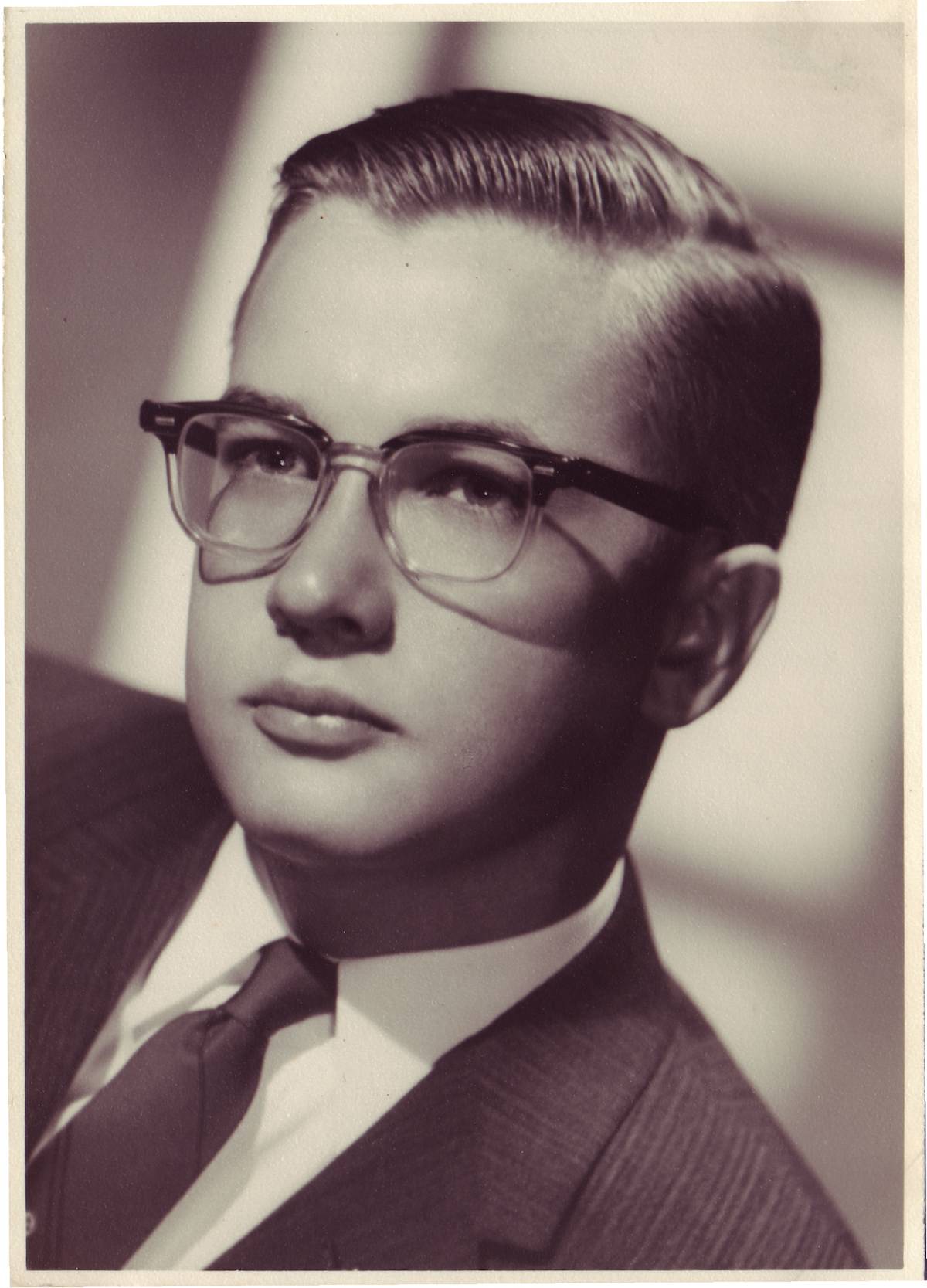

Jeff Joseph, 60, remembers the original 3-D era, while his partner in organizing the festival, 48-year-old Dennis Bartok doesn’t quite, but both have invested much time and passion in this third and possibly final 3-D event. The last one was in 2006, the first in 2003, and both drew satisfyingly large crowds. If the crowds are not quite as large this time, it will probably be because people don’t understand the difference between the latest incarnation of 3-D and the original, seemingly more glorious kind of yesteryear.

“We always said we’d never do another Expo after the last one,” Bartok recalls, since rounding up prints and clearing the rights is a logistical nightmare, but the return of 3-D to movie theaters across the land—a land which is also in 3-D, of course—plus the discovery of previously unseen, very rare 3-D material convinced them to do at least one more. Yes, we have 3-D television now, but the glasses are bulky and the medium has failed to catch on in a big way.

This is likely to be the last 3-D Expo of its kind because, as Joseph says, “If we’d waited just one more year, we probably couldn’t have done it,” not only because some of the materials are so close to deteriorating but because, as Joseph says, “film is dying so quickly in Hollywood that we had trouble even finding an editing room to screen the prints in.”

Indeed, one difference between new and old 3-D is basic to all movies: the rapid fading away of projected 35mm film and theaters that still show it, the near-extinction of the friendly old projectionist (the sole projectionist for the Expo is 70) and the unstoppable rise of digital cinema. “Kiss Me, Kate,” for instance, will be back for a third Expo, but Joseph thinks this will probably be the last time this sole surviving 35mm Technicolor print of it will be dual-projected in a theater as the good Lord intended. Two prints, left-eye and right-eye, were needed for original 3-D, and that meant two perfectly interlocked projectors to play them back as one. If you took your 3-D glasses off, you saw mainly a mucky blur on the screen, whereas if you take off your digital 3-D glasses, you will still see recognizable images.

That is one major difference, and when goaded, both Joseph and Bartok basically agreed with me that the old 3-D had the virtue (and it is a virtue in some things) of being far less subtle than the current kind. Not for nothing was the first 3-D film, “Bwana Devil,” ballyhooed as promising customers “a lion in your lap!” Still, Joseph and Bartok do not denigrate current 3-D, which is much simpler to exhibit than the old kind; besides, RealD, one of the two major 3-D companies now dominating the business, is a sponsor of the Expo. But the entrepreneurs probably wouldn’t be having this big event if 3-D had returned to popularity in its original, fabulous form.

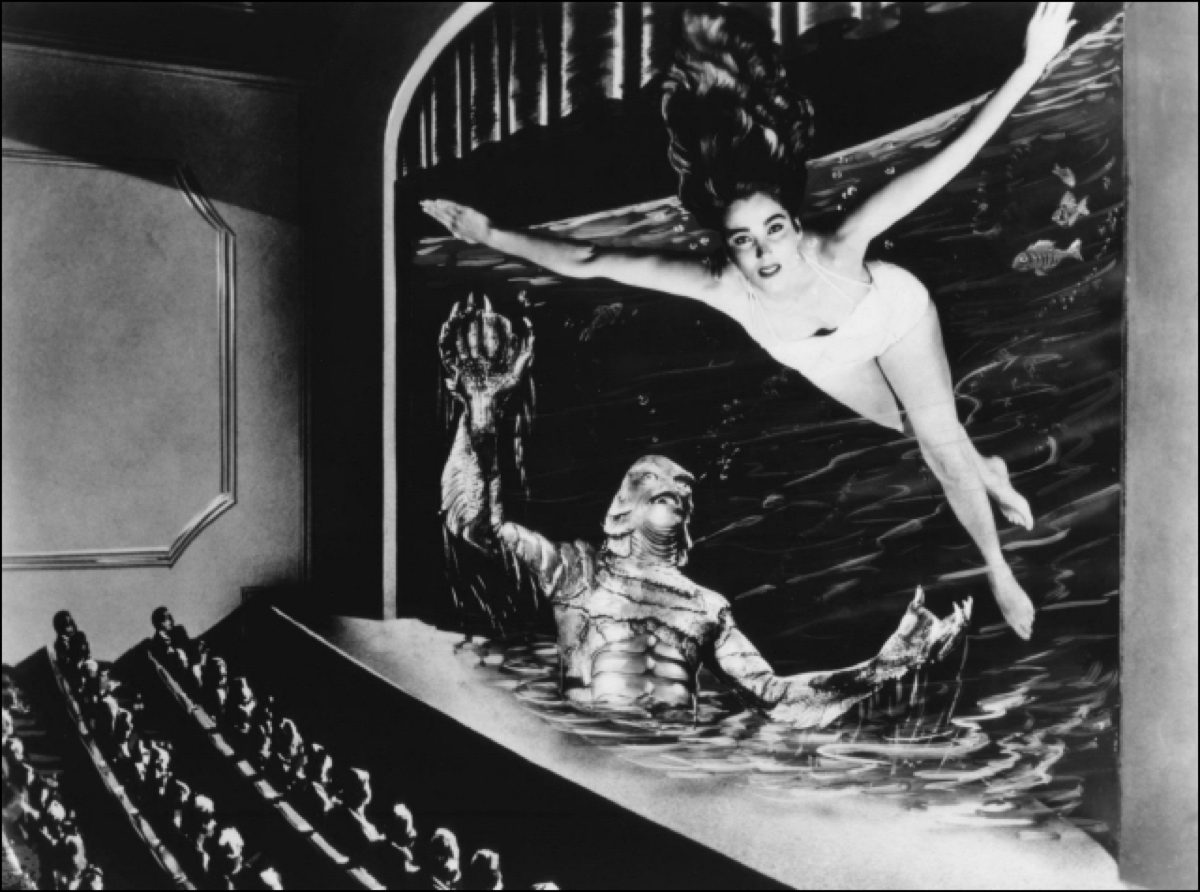

Some of the early 3-D films have already been transferred to digital format for preservation and others will be—but most likely only major, big-studio titles like Warner Bros.’ stupendous “House of Wax” and, from the same studio, Alfred Hitchcock‘s “Dial M for Murder” will be saved. Many of the films in the Expo are the less celebrated kind for which original 3-D was best suited: genre movies like Westerns, science fiction and horror. Expo III will include screenings of the Western “Taza, Son of Cochise,” starring Rock Hudson and directed by Douglas king-of-mush Sirk; Jack Arnold’s “Creature from the Black Lagoon” with one of its stars, Julie Adams, making a personal appearance; and Arnold’s “It Came from Outer Space,” with stars Barbara Rush and Kathleen Hughes personally appearing.

And of course, the schedule includes that warhorse of warhorses in the 3-D universe, and one of Vincent Price’s finest and least epicene (to borrow Pauline Kael’s adjective) performances, the aforementioned “House of Wax,” a gorgeous remake of the 1933 “Mystery of the Wax Museum” which contains arguably the most memorable of all 3-D sequences, one which has nothing to do with the plot of the picture and isn’t in the least bit horrifying: the Paddle-Ball Man.

This is a guy who stands outside the wax museum on opening night and whacks, naturally enough, a ball with a paddle. As he does his tricks, the little ball at the end of the rubber band seems to zip out into the house, and in a Pirandellian spirit, the man with the paddle talks about aiming the ball for, say, the popcorn being held by the fellow in the third row of the movie theater.

(The sequence is beautifully scored, by the way, and though someone else is given screen credit, I’d swear the great Max Steiner himself must have dropped by and written the music for this one part of the film. It’s an iconic sequence if there ever was one, although I try so hard to avoid using that word).

From my childhood, I most vividly remember one other moment from the film, and it is only a moment. A young Charles Bronson, in an Igor-like role as a mute thug who works for the mad maniac running the museum, seems to spring at the heroine, Phyllis Kirk, from right out of the audience. Really, he just rises in silhouette, as I recall, from the lower right of the screen, but it’s a kind of “gotcha” trick that made us kids jump in our seats.

For the record, “House of Wax” was directed by Andre deToth, a man who had only one working eye and thus could not truly appreciate the 3-D effects he was helping to create. An irreverent old Hollywood joke had it that the film was actually codirected by DeToth and Raoul Walsh, because they had two good eyes between them. In later years, DeToth discredited himself by launching a tirade against Alfred Hitchcock, of whom he was perhaps a trifle jealous.

Hitchcock, meanwhile, was reportedly not enthused about working in 3-D, and by the time his “Dial M for Murder” was released, the fad had waned and the picture played mostly 2-D (or “flat”) engagements. But it is a better movie in 3-D than 2—less claustrophobically stagey, for one thing. And there is a certifiable made-for-3-D moment, when Grace Kelly is being strangled by a hired intruder and, forced backwards onto a desktop, she reaches behind her for a pair of scissors with which to defend herself, her arm and the scissors both in-your-face.

Among the rediscovered rarities to be shown at the Egyptian is a 1946 Russian version of “Robinson Crusoe” which was produced in a variation of the 3-D process that apparently was unique to the Soviet Union. There is no English language version of the film and the use of subtitles would be problematic considering the 3-D illusion, but Joseph and Bartok say there’s relatively little dialogue in the movie anyway, and most of it at the end, when the picture breaks into five minutes of good old-fashioned socialist propaganda. It’s highly unlikely that anyone viewing the film will fall victim to the agitprop and convert from capitalism.

The two entrepreneurs told me things about 3-D, then and now, that I certainly never knew—one of them that the two prints, left-eye and right-eye, were virtually identical, so that when the 3-D craze crashed, or when providing films to theaters not rigged for interlocked dual-projection, studios could simply send out either of the two 3-D prints, thus doubling their print inventory. Some of the films will be projected in absolute ultimate authenticity—not just in original analog projected 3-D, but some in their proper wide-screen aspect ratios and some on a literally silver screen, because “silver screen” is not just a fanciful term; the screen really was once silver (made of aluminum, but silver-looking) and though prone to hot-spots, facilitated dazzling 3-D images that a plain white screen could not equal.

Other films to be screened range from the sublime to the preposterous—from bosomy Jane Russell (3-D was “made for” her, said the leering ads) in “The French Line,” a 1954 musical, to a 1953 sci-fi muddle that is frequently cited as one of the worst or at least silliest movies ever made, “Robot Monster,” in which the eponymous villain is a man in a gorilla suit with a goldfish bowl on his head.

Even the lowliest 3-D movies tend to be well-crafted, Joseph says. “‘Robot Monster’ is actually well-shot,’ he says, “and the 3-D is spectacularly good.” Some of the films are campy, yes, but some are brilliant, several are extremely rare, and all of them are explorations into a super-sensory cinema that existed for one crazy golden moment in time. Bless these guys for bringing these films back for another look—every beautiful “D” of them.