Roger ingratiated himself with me the first time we met, which was over lunch, back in the early ’80s, at a snooty-tootie French restaurant in the nation’s capital that I thought would impress both him and his TV buddy Gene Siskel. Lunch over, Roger stood up, grumbled amiably, looked the room over and asked, “Is there a Popeye’s Fried Chicken around here?” Swank eateries were not for him.

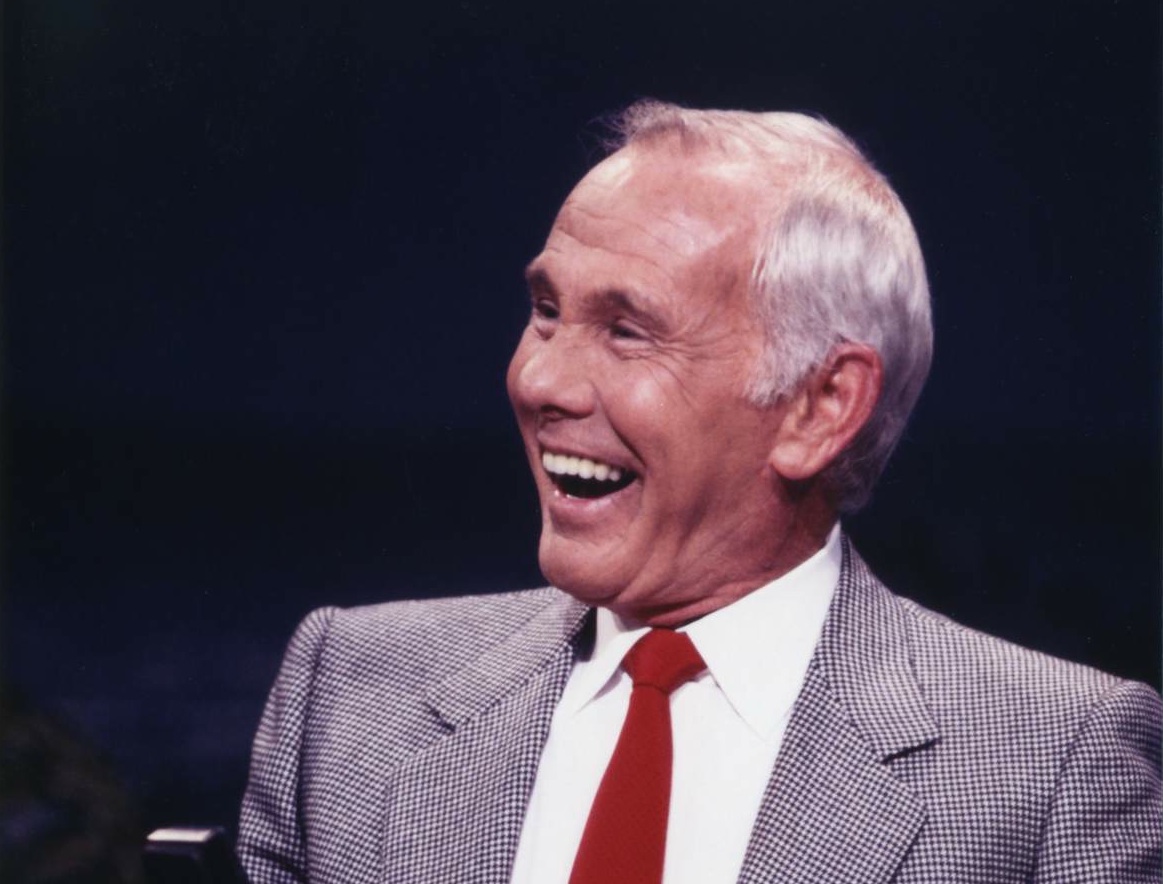

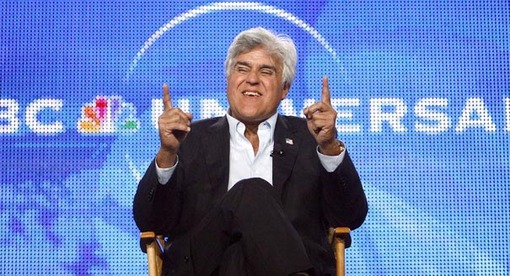

Siskel and Ebert, as they were always billed, had come to Washington, where I worked as a TV critic, to plug their weekly movie-review show. Public TV’s low-budget “Sneak Previews” had become syndicated TV’s lucrative “At the Movies” with Roger and Gene now firmly established as stars like no other. Obligingly, as if anything else would have short-changed everyone in the place, Roger and Gene argued loudly and intermittently all through lunch, just like on TV, and I wrote later that having Siskel and Ebert bicker at your table was like Pavarotti dropping by to sing “Nessun Dorma.” Or words to that effect.

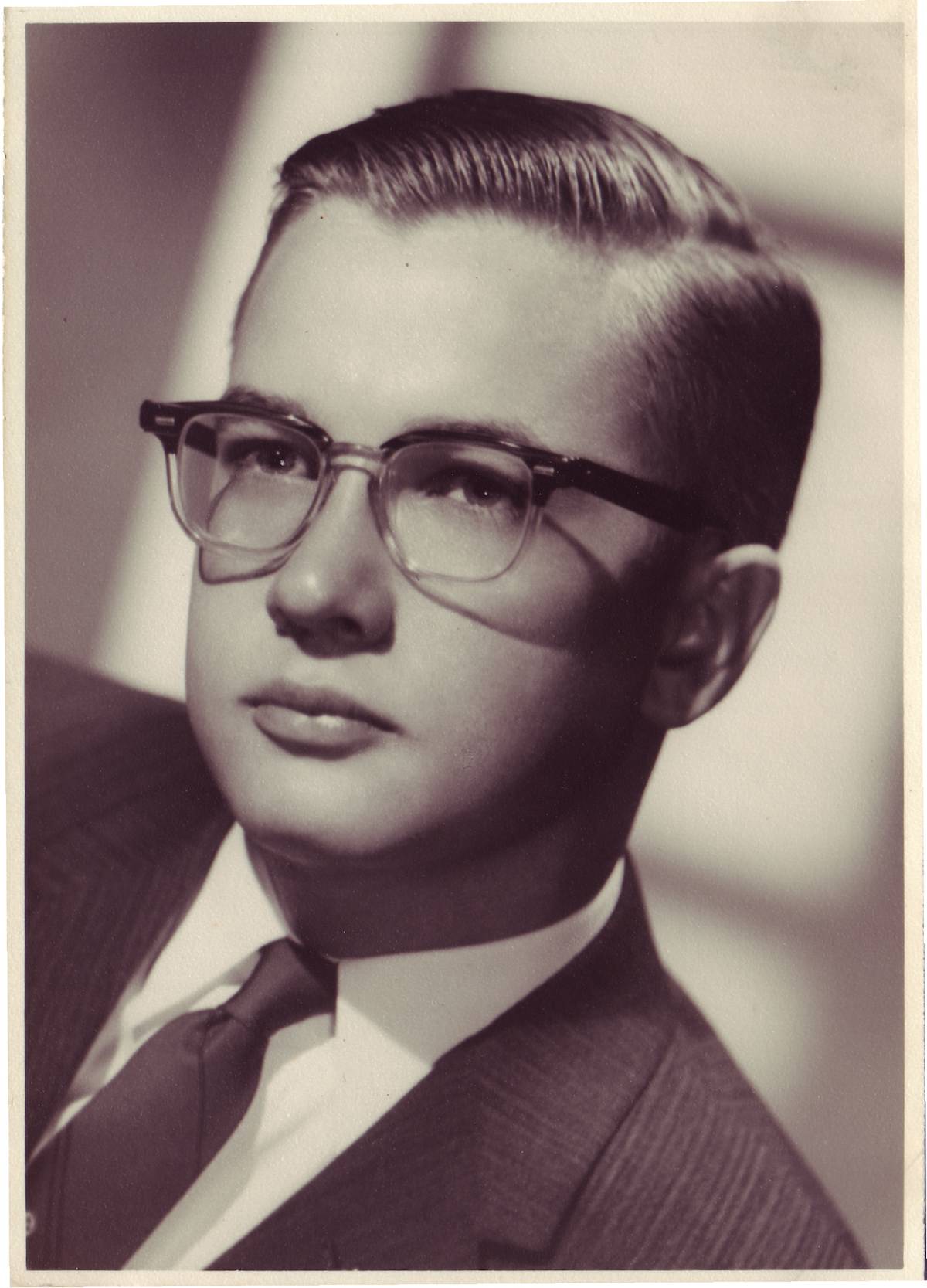

Over the years, Roger and I kind of clickety-clacked along parallel tracks, he reviewing movies on television, me reviewing television in print—and of course, him making millions. To add to the link between us, we looked superficially alike, both of us “portly,” to use a euphemism for the obvious appropriate adjective, both bespectacled, and both Pulitzer Prize winners (Roger was the first film critic ever to win), though I sort of had to beg for mine.

We were also both, at heart, Midwesterners, not the provincial kind you see in “Nebraska,” I hope, but guys who didn’t give a rat’s ass what Woody said to Nora at Elaine’s. We’d run into each other now and then, always fun for me. Among the encounters was a memorial service for the great film critic Pauline Kael, one of the first to spot Roger’s talent, at a cinema in New York. Roger was there with wife Chaz, while most other movie critics had stayed churlishly away.

Kael had died in 2001 at 82. Two years earlier, Siskel died—at the much crueler age of 53. Thus ended what had been a sensationally successful run for the odd couple of criticism, a duo whose dissimilar horizontal-and-vertical profiles and prickly Hope-Crosby badinage had helped make them genuine American icons. Gene was still alive but very ill when I accepted Roger’s invitation to substitute for him on first one, then a second episode of “At the Movies,” taped back-to-back in Chicago, a city I had loved from a childhood lived in one of its more remote suburbs.

Roger assured me that he and Gene had mutually chosen me to fill in, which was lovely to hear, but the experience became traumatic when Gene died before the second show aired. I feared I would look like I was opportunistically auditioning for his job even as he lay dying, but Roger and I both knew such casting would have been absurd. Even if I’d been temperamentally a good contrast, and I wasn’t, two fat guys reviewing movies just wouldn’t work.

What I gleaned from that week in Chicago was how hard it was to see ten movies in one week but, more importantly, what a thoughtful and conscientious mensch Roger was. When I screwed up a reference to one of the film’s actors during the taping, Roger smoothly covered, correcting the error without it showing and thus without shaming me, or necessitating a stop-tape. Later, when the Walt Disney Company, owners of the show, tried to cheat me out of half the compensation agreed upon, Roger stepped in and made them behave. It really was the principle of the thing, and Roger knew about principle.

But I finally got to know Roger well during the last year of his life, although we never spoke—except by email, since illness and surgery had robbed him of his voice, as dirty a trick as fate could play. And here’s the kick: Roger spent many of those emails trying to cheer ME up. I was in shock from having a 39-year tenure yanked out from under me by one of the nation’s newspapers whose money-men decided on downsizing. And loyal old veterans be damned.

“I have a little thingee in my mind that likes everything I write,” Roger wrote me. “You have a little thingee that hates everything you write. You are a writer, not just a TV critic.” That was a short subject, a trailer for the feature attraction, which came a few days later:

“When you split with the Post, you thought,’F— it, that’s that. The bastards.’ Already down on yourself, you felt defeated by the disconnect between your great public success and your private feelings of aimlessness. Your response was to sit passively and let depression come crashing down upon you. You would prove to the bastards that when they thought you were great, that was just one more example of how wrong and deluded they were about everything.”

If anybody knew about facing depression, he did. He had been through an ordeal that made mine look like the sniffles.

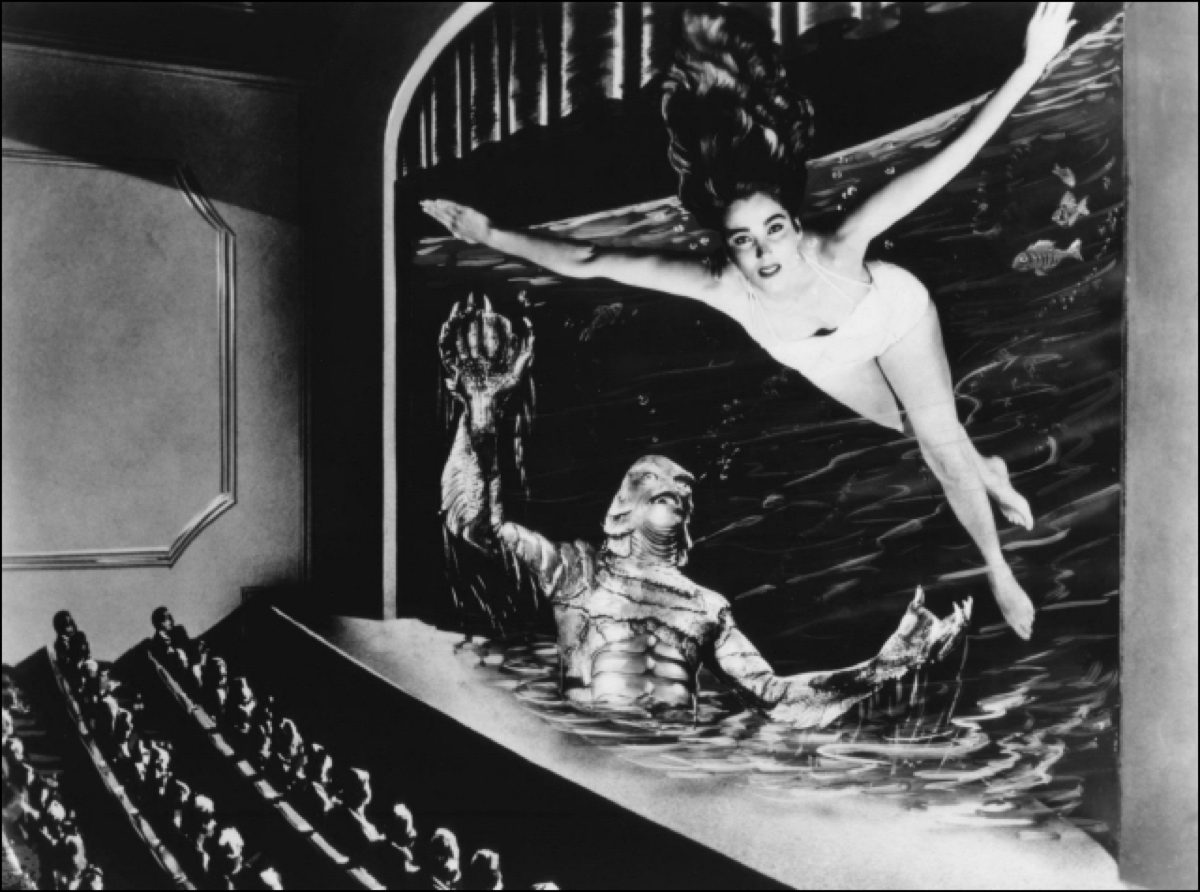

“When, without warning,” he wrote, “I found myself unable to speak ever again, my TV career and life as I knew it were gone overnight. In the bargain, they’d ripped apart my right shoulder to harvest flesh and muscle to ‘rebuild’ my face, which failed so spectacularly that I do now truly look like the Phantom of the Opera. They also took a bone from my right calf, so I could hardly walk. On top of that, I couldn’t eat!

“After rehab, Chaz took me to the Pritikin Longevity Center, a place I had loved.” But instead of letting himself be rehabilitated, he wrote, he sunk into lethargy and stasis. “So as not to seem only staring at the wall, I pretended to sleep.”

And then—”Something happened. I was a newspaperman. Not a ‘writer’ who needed inspiration, a newspaperman trained for years to bang stuff out. Good, bad, it didn’t matter. There was a deadline and a hole to be filled. I wanted to see that movie ‘The Queen,’ and I saw it, I wrote a review, because I didn’t go to see these movies for my own amusement, you see. I get paid!”

He was making his epiphany, mine. Maybe I didn’t leap up and trill “whoopee,” but I was jolted in a positive way. To quote all of Roger’s therapeutic praise would look self-aggrandizing, but he went further, issuing another invitation, this time for me to write for what he called his “blog” but which became his website and is now part of his legacy. I’m still not happy about writing, but if not for Roger, I’d be searching for new walls to stare at right now.

Writers, journalists, critics, whatever, are not usually kind to one another. While being jabbed and maligned at the old roost, with a guy who wanted my job circulating hostile internal memos (yes, even paranoids have enemies), a New York essayist used his blog to offer up about a thousand words on why I should be fired. Or maybe shot, it wasn’t clear. But eliminated. It was unmistakably one writer urging that another be forcibly retired.

The thing is, those two monsters were typical, whereas Roger was the gloriously generous and confident exception. He was nothing but encouraging, ever, always. He forced me to see daylight. He helped me out of a deep hole. And then he died.

It was fitting that my best friend called with the news. He didn’t have to spell it out; I could hear it in his “hello.” He asked if I were watching the news. When your best friend asks you that, you know there’s something terrible happening. I asked him a one-word question: “Roger?” His silence was the answer. I felt all the air go out of me. I thought I was literally imploding. It was the same devastating sensation I’d felt twelve years earlier, standing in the National Cathedral as a casket containing the earthly remains of Katharine Graham passed me on its way up the aisle.

During our year’s correspondence, which amounted to nearly 200 emails from each of us, I told Roger I’d never known, until having just read it somewhere, that in the darkest days of his nightmare, he was in fact declared dead by doctors. I received this defiant and ebullient reply: “Yes, but the bastards were wrong!”

This was Roger Ebert. This was my friend.