1.

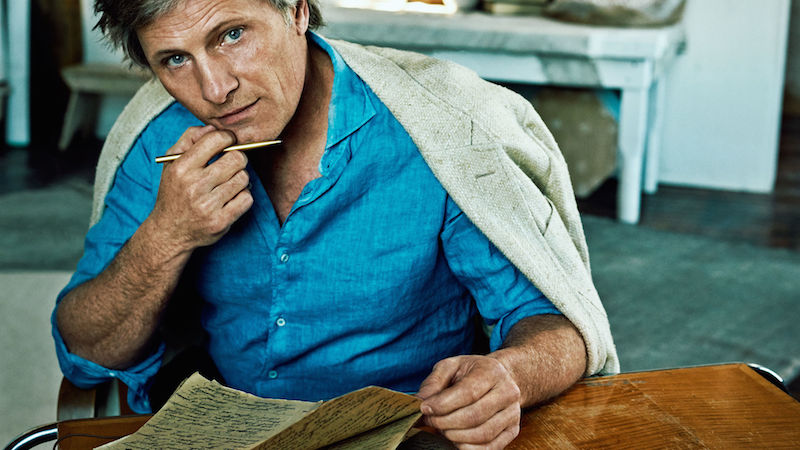

“Why Viggo Mortensen Is Off the Grid“: An excellent profile of the actor from Esquire‘s Lisa DePaulo.

“We’re here to talk about Mortensen’s new movie, a subversive and surprising family drama called ‘Captain Fantastic,’ and we’re here here, in upstate New York, because Mortensen has taken some time off from his life in Madrid to care for his dying father. To see him to the end, same as he did for his mother, Grace, who passed away a year ago. Grace was a saint. His father, also named Viggo Peter Mortensen, not so much. But you do what you have to do. The old man is in Watertown, an hour and a half from the Syracuse airport, where Mortensen went to high school and where we are headed now. And so we drive. Or, rather, he drives. For the next eight hours, for about 250 miles, up to and around Watertown, through the Adirondacks and not quite to Canada—though he does ask if I brought my passport—with periodic stops at diners and waterfalls, lakes and trout ponds, his mother’s grave and finally his father’s farmhouse. Viggo loves to drive. Sometimes he drives cross-country, just for the hell of it. And yet he has rented a Ford Fusion. ‘They always do this thing where they try to upgrade me to some fancy f—king car.’ But he doesn’t want a fancy f—king car. At times, he spontaneously pulls over to the side of the road for a good five or ten minutes to finish a train of thought—about life or death or demons or fears or his favorite soccer team in Argentina, San Lorenzo. About the time in the wilds of New Zealand when he skinned, cooked, and ate his own roadkill. (‘It was there.’) About how much he loves the militant Chomskyite he plays in ‘Captain Fantastic,’ a father of six who decides to raise his kids in the isolated wilderness of the Pacific Northwest. We could’ve gone straight to Watertown and stayed there, and we could’ve gotten there a hell of a lot faster, but Mortensen, his two hands resting gently on the bottom of the steering wheel, doesn’t like to drive too fast. He doesn’t want to miss a thing.”

2.

“How Netflix Became Hollywood’s Frenemy“: According to Fortune‘s Michal Lev-Ram.

“Just a few years ago it would have sounded absurd for a Netflix exec to talk about what makes good storytelling. But these days the Silicon Valley interloper is arguably the biggest influencer in Hollywood. Netflix has harnessed the shock waves of the broadband revolution, becoming simultaneously one of the top-performing tech companies—its stock rose 134% in 2015, the best return of any Fortune 500 member—and one of the world’s fastest-growing entertainment businesses. It’s spending $5 billion this year on television and film content, a spree that far outpaces its rivals—and underscores the pressure it’s exerting on those rivals to rethink the way they operate. Netflix’s refusal to make viewership numbers available has thrown a wrench into television’s ratings-driven business models. Its pioneering practice of buying up an entire season (or two) of a series without requiring a pilot is luring writers, actors, and producers away from traditional television. And by releasing full seasons in one fell swoop and streaming them ad-free, Netflix has trained viewers to binge—and to be increasingly impatient with once-a-week episodic television and commercial breaks. And that’s just what’s on TV. Netflix is encroaching on the big screen too, outbidding incumbent studios for high-profile projects like Bright, a Will Smith cop thriller it snapped up for a reported $90 million this year. More alarmingly, it has been lobbying against traditional theater-only cinematic runs for new movie releases—leading John Fithian, CEO of the National Association of Theatre Owners trade organization, to call out Netflix at a recent conference as a ‘grave threat to the movie business.’”

3.

“Ted Kotcheff on Making ‘First Blood,’ Changing Rambo’s Suicide Mission and (Not) Working with Kirk Douglas“: Another essential chat with Filmmaker Magazine‘s Jim Hemphill.

“I was getting it set up and the producers rushed over to me: ‘Kotcheff, what the f—k are you doing?’ I said, ‘I’m shooting an alternate ending.’ ‘An alternate ending? We agreed on the ending. It’s a suicide mission. You’re over budget and over schedule, you don’t have the money to do two endings.’ I said, ‘I don’t take s—t from producers. Get off my set. I’m going to get the shot. It’s only going to take me two hours.’ I told them, ‘I’ve got a hunch – when we find an American distributor, they’re going to want this ending. They’re going to want Rambo to survive.’ Sure enough, we got the shot, finished the film, and took it with the original ending to Orion for distribution. And Mike Medavoy, who ran it, said, ‘I love this film, but I hate the ending.’ Andy Vajna was so angry he leapt across the desk and tried to punch Mike Medavoy in the face. We went to a suburban theatre in Las Vegas to test the film, and I knew it was going to be a success – the audience was so involved. Then Rambo commits hari-kari. You could have heard a pin drop. A voice in the silence says ‘If the director of this film is here, we should string him up from the nearest lamp post for doing this to Rambo.’ I turned to my wife and said, ‘Let’s get the hell out of here,’ and ran out of the theatre. The cards came back and all five hundred of them were practically identical – everyone thought it was a great action movie with a horrible ending. You could see consternation growing on the faces of the producers as they read card after card.”

4.

“Insomnia and Philosophy“: Food for thought from The Book of Life.

“Rather than immediately medicalising insomnia, we should perhaps try to understand where it springs from in human nature – and what it might – in its own confused way – be trying to tell us.And in many – though, note, not all – cases, it may go something like this: insomnia is the mind’s revenge for something extremely important we have forgotten to do in the day, namely, think.Most of us do of course have a great deal on our minds during the daylight hours, but these tend to be practical, procedural, immediate matters – the sort that keep at bay the larger, deeper questions about our direction, purpose and values. It’s tempting to think of philosophy as a remote specialised discipline of relevance to only a few academically minded sorts. But what philosophy really wants from us – which is that we should lead an examined, self-aware life – is in truth a basic necessity for every human being, as vital as water or exercise – so much so that if we don’t regularly do enough philosophy, if we don’t constantly make time to interrogate ourselves, question our plans, explore our talents and think over our relationships, we will pay a very heavy price. We’ll be stripped of the capacity to carry on our lives with enough rest in our bones.”

5.

“Bruce Dern, at 80, Reflects on His Career, Working with Clint Eastwood and Alfred Hitchcock“: In conversation with Variety‘s Tim Gray.

“Dern, who turns 80 on Saturday, got his professional start by working with Lee Strasberg and Elia Kazan, and his career is dotted with big names that he worked with: John Wayne, Clint Eastwood, Robert Redford, Paul Newman, Bette Davis, Barbara Stanwyck, Roger Corman, Jane Fonda and Jack Nicholson, to name a few. He also had encounters with such diverse characters as notorious west coast mobster Mickey Cohen and noted pianist Vladimir Ashkenazy.Dern recently told Variety, ‘I’ve worked with six geniuses as directors: Kazan, Alfred Hitchcock, Douglas Trumbull — when he looks through the camera, he sees something no one else sees; he sees magic — Francis Coppola, Alexander Payne and Quentin Tarantino.’ In such heady company, Dern shrugs that he’s lucky, adding, ‘I’m just Brucie from Winnetka.’ Dern was a journalism major at the University of Pennsylvania, but dropped out to become an actor. With no professional experience, he was accepted by Strasberg and Kazan for their famed Actors Studio. Dern was cast in the studio’s first attempt to branch out into theater productions, a revival of Sean O’Casey’s ‘Shadow of a Gunman,’ directed by Jack Garfein.In its November 26, 1958, review, Variety said, ‘Bruce Dern adds brief vigor in the small part of a deadly-quiet terrorist.’ The Herald Tribune’s Walter Kerr disliked the production, but said, ‘The play’s saving grace is a 52-second performance by a heretofore unknown actor named Bruce Stern.’”

Image of the Day

The Chive presents a series of fabulous director/movie mash-up sculptures from artist Mike Leavitt.

Video of the Day

The Videoblogs Dialogue is seeking videoblogs pertaining to themes of mental health and/or personal struggle. Participants are eligible to win a $2,000 cash prize and mentorship package, and submissions close on Monday, June 20th. Click here for more info.