From Jason Haggstrom (haggie), Reel 3:

The opening shot of Robert Altman's "The Player" establishes the film as a self-reflexive deconstruction of the Hollywood system and those who run it. With its prolonged shot length, the take is also designed as a means to introduce the bevy of players who work on the lot and to setup the film's general plot--or at least its tone--as a thriller/murder mystery.

The first image in this extended opening shot is of a film set--a painting of one, to be precise. We hear the sounds of a film crew before a clapper pops into the frame. The (off-screen) director shouts "And... action" informing the audience that the film should be viewed as a construct, a film. The camera tracks back to reveal its location on a Hollywood studio lot where movies are described not in accolades of quality, but of quantity with an oversized sign that reads, "Movies, now more than ever."

The lot is filled with commotion. Writers come and go (some invited, some not) as do executives, pages, and assistants. The political hierarchy is highlighted through dialog and interactions that expose the value system of Hollywood. The most powerful arrive by car; high-end models pervade the mise-en-scène in all of the take's exterior moments. An assistant is made to run (literally, and in high heels) for the mail, and then -- before she even has a chance to catch her breath -- to park an executive's car.

Stories are pitched and then quickly reshaped in order to better match the desires of the studio. Arty foreign films and their directors are mentioned, but not by those who hold any power. The studio's head of security, Walter, bends the ears of anyone who will listen as he blathers on and on about extended takes as though the length of a shot alone determines its artistic value. Altman acknowledges Walter's interests as well in making this opening shot a protracted eight minutes in length. After all, Altman is making this film within the studio system. He sees no difference between the security man and the studio executive when it comes to opinions on how he should shoot his film. If he's to get The Player made, he must please the suits.

While the film's camera is clearly operating from within the studio (literally and figuratively), it is not so privileged that it can get into the office of the mighty executive, Griffin Mill. Instead, we are forced into the position of voyeur listening to pitches from behind Mill's window, crouched beneath a plant. It's a typical position for us spectators, but also a metaphoric camera placement that further establishes the film's position as a piece of metacinema.

Mill favors the pitches that are analogous with previously successful films. If it is to star Julia Roberts, has "a heart," or attempts to amalgamate proven formulas (no matter how disparate) such as "Pretty Woman" and "Out of Africa," then it has a good shot at being made. It's a scathing vision of a Hollywood that privileges repetition over artistry, and of its complex system of social rules that were erected with only profit in mind. But still, in this system that privileges the powerful, there is one message that gets through from someone with no presence at all: a character who is, and will remain, unseen and unnamed. In terms of "the pictures," this would normally be the least powerful position of all.

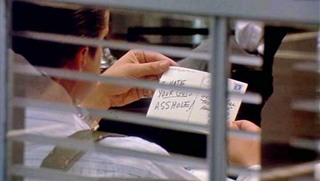

When the page, Jimmy, is involved in a crash, the camera tilts down to draw attention to a postcard (and away from the "unimportant" man who is lying injured on the ground). It reads, "Your Hollywood is Dead," and features images of legends from years gone by such as Charlie Chaplin. Contrasting this message of the demise of the Golden Age of Hollywood with the film's setting in a Hollywood driven not by art but by profit furthers the film's theme of modern Hollywood deconstruction.

Who is sending the postcards? Is it the director of this film, Robert Altman, himself? When the postcard ends up in Mills' hands and is revealed to be a death threat, the film's nature as a self-reflexive, deconstructionist text is married to something more conventional: a thriller/murder mystery. Movies may be "more than ever," but the sender of the postcards--and the film itself--believes that we might be better off with a change in management.

JE: Thanks, haggie! (And thanks for the concluding reference to the Hal Phillip Walker campaign in "Nashville.") That first image of the mural reminds me of the last shot (or last few shots) of another great Hollywood movie-movie, Billy Wilder's 1950 "Sunset Boulevard," with Max/Mr. DeMille at the foot of Norma Desmond's staircase, directing her Salomé descent, until she decomposes into her final close-up....

The tension is thicker than the valley smog on the lot this morning, from that first trompe l'oeil image with the arm and the clapboard (this whole movie is trompe l'oeil), to the jarring alarm bell that signals all quiet on the set, to Thomas Newman's nervous, subtly discordant music. It's all quite unsettling: People are scurrying around, on foot and in vehicles, making and missing appointments, pitching images of themselves and the movies in their heads in hope someone will buy. Everything is a status symbol, from your means of conveyance (car, golf cart, bicycle) to your office, to your lot pass.

The first thing that happens after the clapboard snaps is an incoming phone call, which the receptionist mishandles by telling "Mr. Levy" that her boss, studio head Joel Levison, is not in yet. She is immediately reprimanded by an obviously experienced executive assistant (the great Dina Merrill), who reminds her that she should always say he's "in" -- in a meeting, in a conference, but always "in." Still, she's a little worried about his tardiness and sends the girl off to get the trades right away, before he arrives. There may be some disturbing news in them.

As the crane pulls back and we see the studio tagline -- the utterly inane "Movies... Now More Than Ever" -- we should remember that Altman's "Nashville" (1975) was born out of his disillusionment after the re-election of Richard Nixon in 1972, in which the CREEPy campaign slogan was "President Nixon. Now more than ever."

("Nashville" wound up being shot during the summer of 1974, when the Watergate hearings were on television every day, and that well-justified political cynicism seeped into the picture, too. In 1984, Altman would film the one-man political fantasy "Secret Honor," with Philip Baker Hall as Richard Nixon, drunkenly making his last White House tape.)

As Tewkesbury recalled in the introduction to the Bantam paperback edition of her "Nashville" screenplay (which was actually a transcript of the theatrical release version of the picture):

The day after Nixon was elected for the second time, the campaign where Wallace was shot, I was with Robert Altman and his wife in New York. There had been a storm of extreme proportions the previous night and as we walked down the street through the debris, Altman shook his head and said something about nature's omens. The election had been a lie.

"The Player," then, sets out to do in Hollywood more or less what "Nashville" had done in the Country Music Capitol. Altman had spent the last several years in a kind of exile in France. Tewkesbury (who played the publicist escorting the real-life Elliott Gould and Julie Christie around Nashville) appears in this opening shot, pitching a movie idea with Patricia Resnick, another screenwriter who'd worked on Altman's "3 Women" (uncredited) and "A Wedding" -- as well as the hit comedy "Nine to Five," starring Lily Tomlin, Jane Fonda and Dolly Parton. As Griffin Mill (Tim Robbins) paraphrases their pitch, it's like "The Gods Must Be Crazy" except that the Coke bottle is a television actress -- to be played by Julia Roberts (everybody's first choice in 1992), or perhaps Goldie Hawn. Buck Henry pitches... a preposterous sequel: "The Graduate, Part 2."

The unease builds. Annie Ross (the jazz singer from Lambert, Hendricks and Ross who would appear with Lori Singer in one part of Altman's next project, the Raymond Carver adaptation "Short Cuts") is one of the executives who discuss rumors that Larry Levy may displace Griffin Mill. Jeremy Piven (Ari Gold on HBO's "Entourage") plays a nervous tour guide showing a group of Japanese (investors?) around the lot. This was shortly after the unthinkable had happened in Hollywood, and a Japanese company, Sony, had purchased Columbia and Tri-Star Pictures and moved their headquarters into the Irving Thalberg building on the old MGM lot in Culver City. The company became known as Sony Pictures Entertainment in 1991.

Finally, Alan Rudolph, longtime Altman associate (background director on "Nashville"!) and the director of such films as "Choose Me," "Trouble in Mind," "The Moderns" and "Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle" -- although Jimmy the errand boy mistakes him for Martin Scorsese -- pitches something he describes as a kind of "Ghost" meets "The Manchurian Candidate" -- but with heart. He says he thinks he can talk to Bruce Willis about starring. Indeed, just the year before Rudolph had stepped in to finish the Willis-Demi Moore thriller "Mortal Thoughts" after differences with the previous director had caused the studio to shut down production.

And there are hints of actual violence. When Jimmy has his off-camera collision with a golf cart, we first glimpse the vaguely threatening, handwritten postcard ("Your Hollywood is Dead"*) that troubles Griffin in his final pitch meeting, with Alan Rudolph. The shot ends with him looking out the window, over his shoulder. And that's the way he'll feel for the rest of the picture... until things come full circle.

(NOTE: Not all of the frame grabs above are presented in chronological order.)

* When I interviewed Altman for "The Player," Hollywood was still thriving and he seemed cautiously optimistic about his own future making movies. (Indeed, he proved to be on the verge of a career renaissance that would include "Short Cuts," "Kansas City," "Gosford Park" and "A Prairie Home Companion.") He said he'd simply come to realize that he and the Hollywood studios were not in the same business. They made their pictures; he made his.